How we're working to save them:

- Create volitional passage to spawning habitat in Battle Creek.

- Increase juvenile survival by restoring floodplain habitats along lower Battle Creek, the mainstem Sacramento River, and the Yolo and Sutter bypasses.

- The proposed trap and haul programs to truck both adult and juvenile winter run Chinook around Keswick, Shasta, and McCloud dams should be viewed as a last resort extinction prevention effort which should only be implemented after all other restoration measures have been exhausted.

Where to find Sacramento River Winter-Run Chinook Salmon:

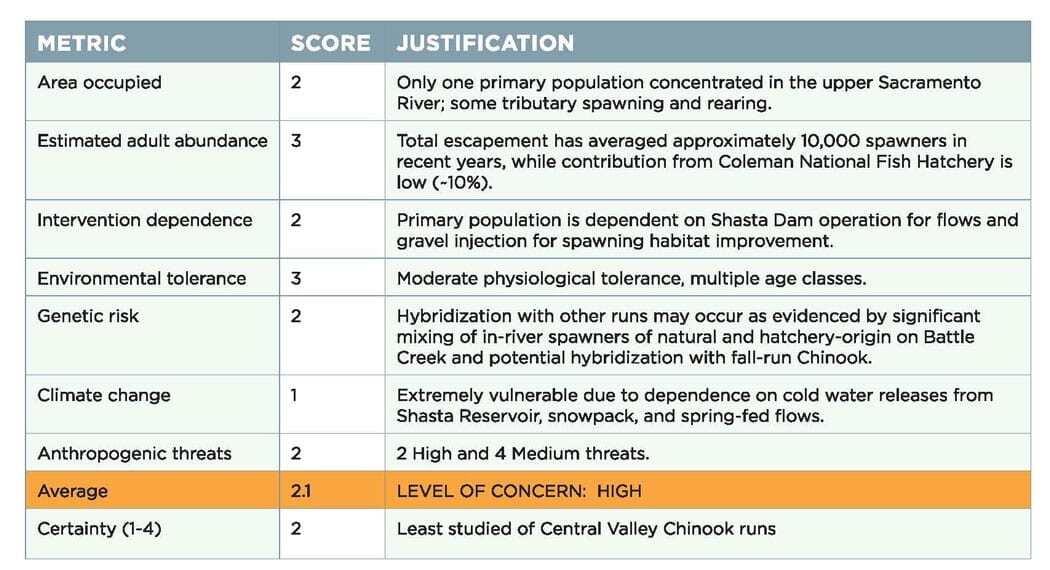

Sacramento River Winter-Run Chinook Salmon Distribution

Historically, Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon migrated to the headwaters of the Sacramento, Pit, and McCloud rivers, as well as Battle Creek (Tehama County). All historical spawning habitat is now upstream of major dams. Today, the one remaining population spawns in the mainstem Sacramento River immediately downstream of Keswick Dam near Redding.

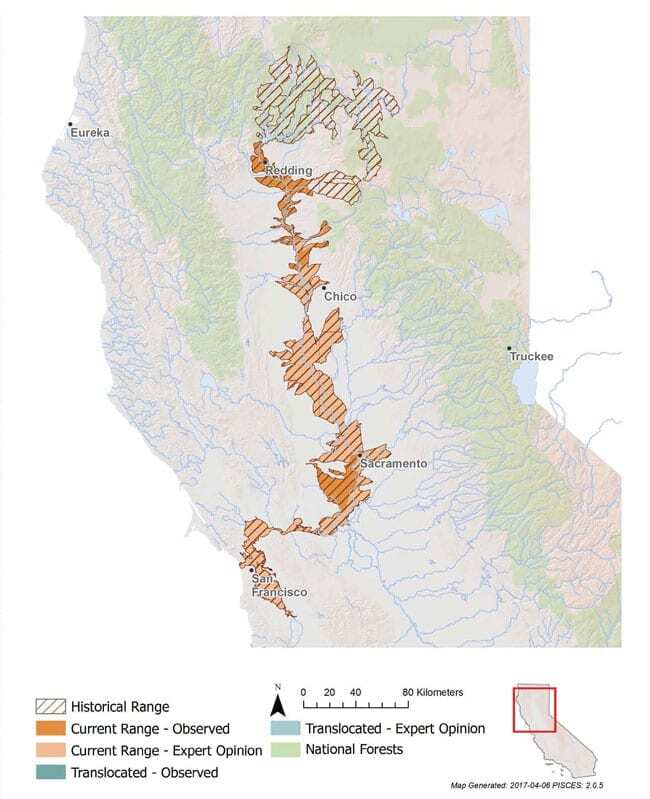

How they Sacramento River Winter-Run Chinook Salmon Scored:

Characteristics

While there are no obvious physical differences between Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon and other Chinook in the Central Valley, they tend to be smaller than fish of other runs.

Abundance

Historically, winter-run Chinook salmon runs likely numbered around 200,000 spawning adults per year. They have been in serious decline over the last decade, with an estimated 827 adults returning to spawn in 2011. Accurate abundance data has been difficult to collect, because fish assumed to be winter-run Chinook were later discovered to be either spring- or late fall-run fish using better genetic techniques. In 2015, about 3,500 winter-run Chinook adults returned to spawn, but warm water releases from Shasta Reservoir significantly reduced egg and juvenile survival and will likely lead to low adult returns for the next two to three years.

Habitat & Behavior

Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon evolved in stable, cold, spring-fed streams in high elevation headwaters that are now blocked by large dams on the upper Sacramento River, McCloud River, and Battle Creek. Adults enter fresh water as sexually immature fish from January to May, with a peak in mid-March. Historically, they would hold in spring-fed streams to mature before spawning from April through August, with eggs incubating during the hot summer months. Winter-run juveniles appear to occupy fresh water year-round, and generally prefer temperatures between 10- 16°C (50-61°F). Fry emerge from redds from July to mid-October and juveniles feed for five to 10 months before migrating downstream in January through April during the first high flows of the rainy season, moving mostly at night to avoid predators. Historically, juveniles would spend up to several months feeding and growing in off-channel habitats in the lower river and Delta. Juvenile winter-run Chinook feed for longer periods in fresh water compared to other Chinook, growing to relatively large sizes without having to over-summer in fresh water when conditions are most stressful.

Genetics

While the four Central Valley Chinook salmon runs are each genetically distinct, they are more closely related to each other than they are to Chinook salmon in other regions. Historically, there were four separate populations of winter-run Chinook salmon that spawned in headwater reaches of the upper Sacramento, McCloud, and Pit rivers and Battle Creek.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Human use of streams, lakes, and surrounding watersheds for recreation has greatly increased with population expansion. Boating, swimming, angling, off-road vehicles, ski resorts, golf courses and other activities or land uses can negatively impact salmonid populations and their habitats. The impacts are generally minor; however, concentration of multiple activities in one region or time of year may have cumulative impacts.

Human use of streams, lakes, and surrounding watersheds for recreation has greatly increased with population expansion. Boating, swimming, angling, off-road vehicles, ski resorts, golf courses and other activities or land uses can negatively impact salmonid populations and their habitats. The impacts are generally minor; however, concentration of multiple activities in one region or time of year may have cumulative impacts.