By Kara Glenwright, Communications Associate

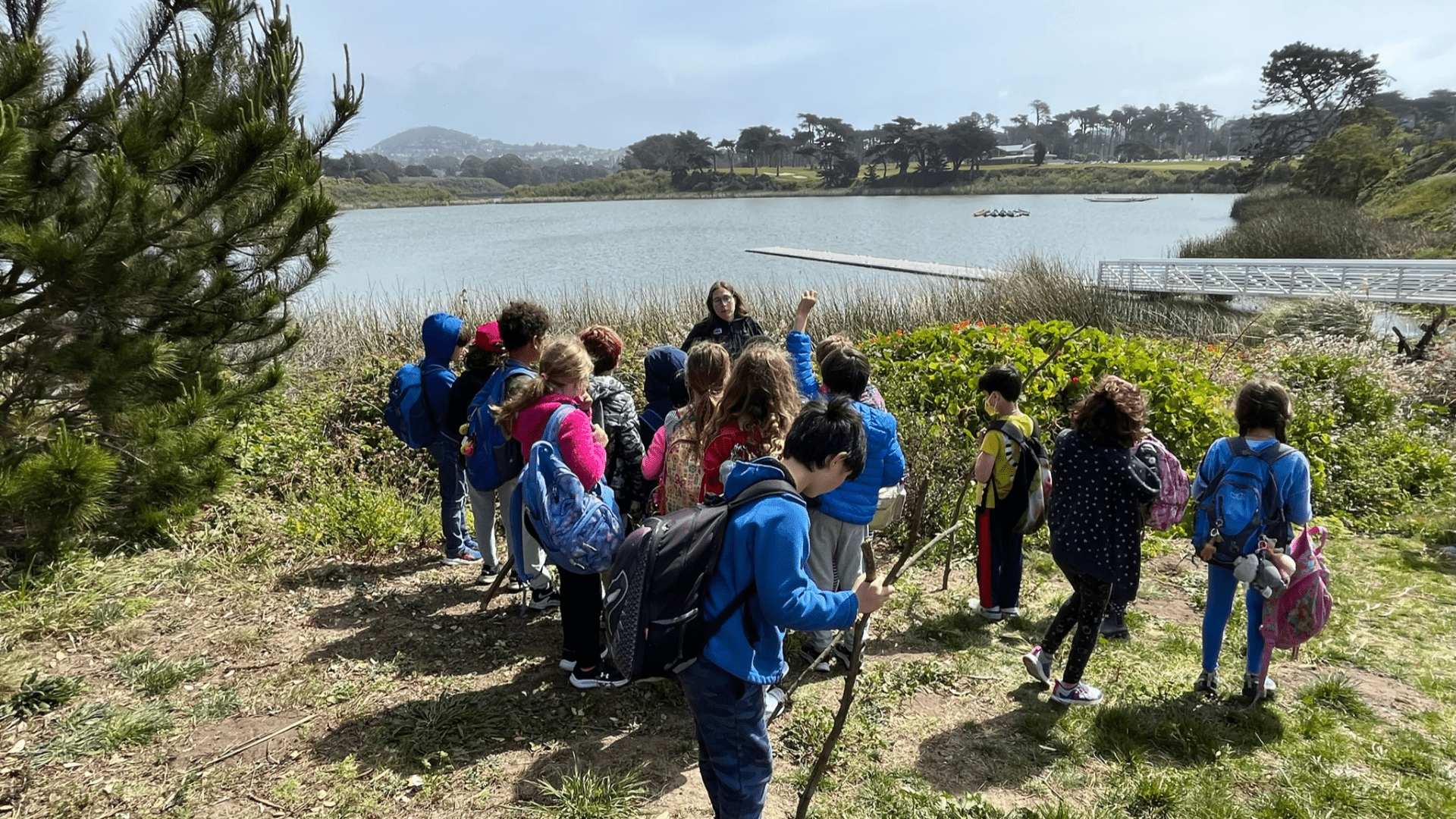

The sun is shining —a rare fog free day on the coast of San Mateo County, California. Patrick Samuel, CalTrout’s Bay Area Region Director, leads a group of CalTrout members and some staff, imparting us with his wealth of knowledge of this area.

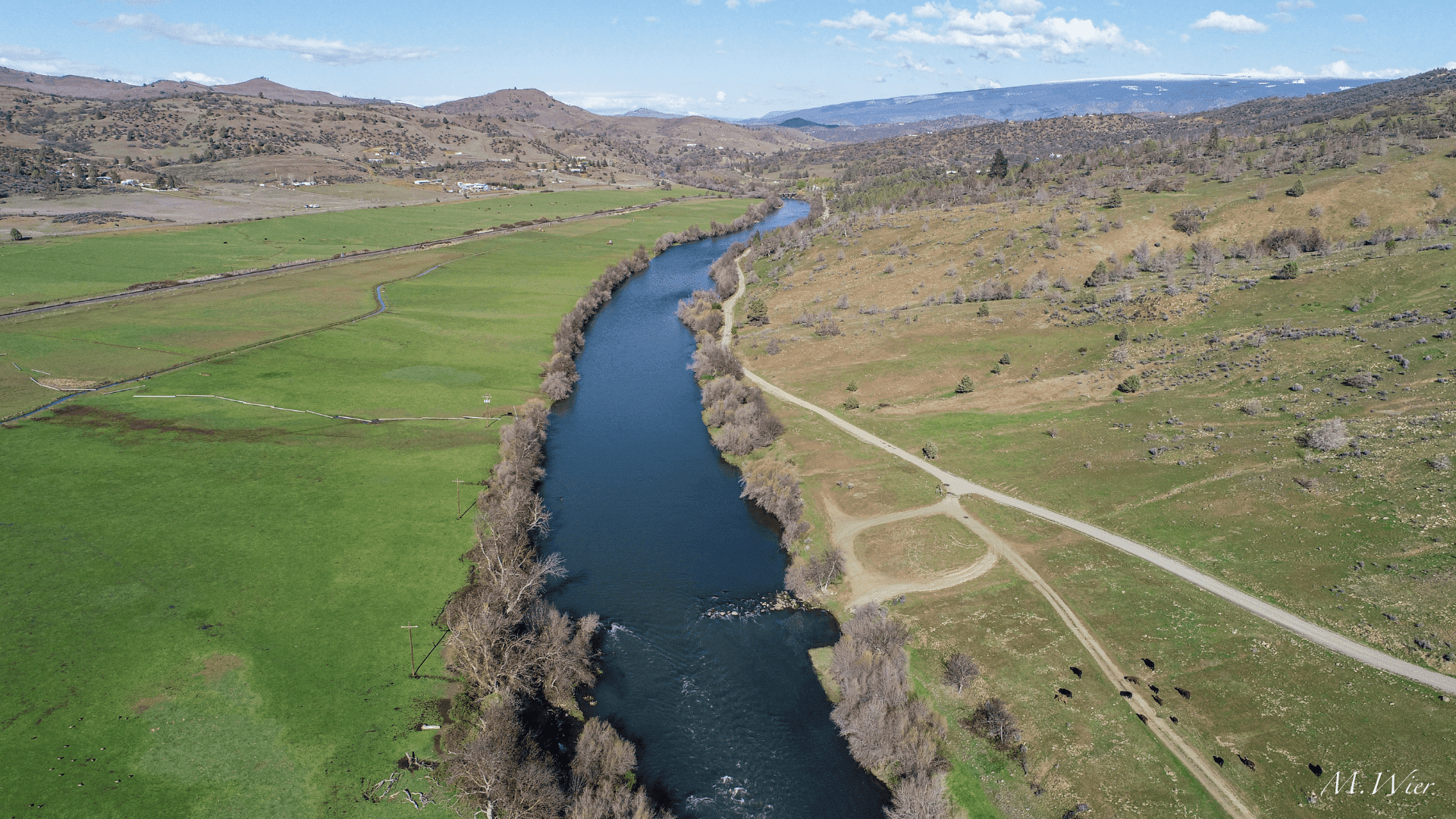

We are standing on ancestral Ohlone Tribal land in the parking lot of Pescadero State Beach with the wind rushing towards us from across the ocean. To our east, Pescadero Marsh lies resting in the sun. To our west, its water flows lazily out to sea via the mouths of Pescadero Creek and Butano Creek converging. This place is special for a number of reasons: it is one of the best remaining habitats for coastal steelhead in the Bay Area, it offers unparalleled opportunity for anglers, and is also beautiful enough to steal your breath.

Cover Photo: Michael Wier

Steelhead in Pescadero

Central California Coast steelhead historically thrived in Bay Area waters, but today, populations are collapsing with only a fraction of their historical abundance remaining, according to CalTrout's SOS II Report. California Trout, along with our partners at California Department of Fish and Wildlife, San Mateo Resource Conservation District (RCD), Trout Unlimited, and others such as California State Parks, private landowners, and NOAA Fisheries- the federal agency tasked with managing steelhead and salmon nationwide- are determined to improve this system for the overall health of the watershed and for its inhabitants — both fish and people.

Background Photo: Michael Wier

Pescadero, which in Spanish translates to fishmonger, earns its name from a long and rich history of fishing. However, the landscape and fishery that we see today surrounding Pescadero Marsh and its connected watersheds are severely altered. Throughout its history, the area has been farmed and diked. Timber logging and agricultural activities have contributed to massive land use changes. One of the results of these changes is anoxic waters in the marsh leading to at least 15 documented fish kills over the last two decades.

Why did these fish kills occur?

Simply put, human land use in the watershed causes changes that lead to oxygen-poor waters. When the lagoon is breached, water deficient in oxygen can lead to fish kills. To learn more about the complexities surrounding water quality in Pescadero, check out these resources from CDFW and San Mateo County RCD.

Juvenile steelhead are the main inhabitants of Pescadero Marsh, feeding and growing there, before continuing on to the ocean. Over the past few decades, their population suffered immense losses due to these catastrophic fish kills.

However, because of the hard work and dedication of our partners at RCD, today Butano Creek is reconnected to the marsh. Andrew Hall, Senior Conservation Project Manager at San Mateo RCD, walked us through the multi-benefit dredging project he managed that reconnected the Butano watershed. This provided many benefits: no more fish kills, less flooding for residents, and restored access for coho salmon and steelhead to migrate up Butano Creek.

Sean Cochran, CDFW District Fisheries Biologist, told us about CDFW fisheries and water quality monitoring in the lagoon that has occurred from 2014 to present, done in collaboration with CA State Parks. He explained what the agencies have learned and their interim lagoon management efforts that were utilized before the completion of a dredging project in 2017. Things are looking up: the last documented fish kill in Pescadero was in 2016.

A Computer on the Creek

Traveling a few miles east from the marsh, on Pescadero Creek Road, we arrive to warmer weather and far less wind. We are now in the town of Pescadero proper, on the banks of Pescadero Creek with glimpses of its water shrouded by trees and brush. It is a quiet spot except for the rustling of the tree branches — certainly not the kind of place you would expect to find anything out of the ordinary. And yet, as we push down thistles with our shoes, coming within a stone’s throw of the water, a large metal box appears. Patrick Samuel explains this large metal box contains a computer; CalTrout works with partners to use this computer in tracking tagged steelhead and coho salmon passing by an antenna in the creek. The information gathered here is used to complement ongoing fish surveys in the lagoon and upper watershed in order to better understand the population, the fishes' usage of now-connected Butano Creek, and to understand the timing of fish migratory behavior for both juvenile and adult coho salmon and steelhead in the watershed.

In 2014, CDFW began annual surveys of the fish populations in the watershed. Then in 2017, they began tagging steelhead in the lagoon with PIT tags to monitor the population and to gauge performance of the restoration project. Monitoring data helps us understand whether fish are recolonizing their historic habitat, allows us to assess their migration timing and life histories, and supplements our ongoing surveys in the marsh to add context to population estimates.

What is a PIT tag? PIT stands for Passive Integrative Transponder. These tags are typically around 1.25 cm in length and are safely inserted in juvenile steelhead using a hypodermic needle. Once inserted, the tags can provide important information about fish movement and behaviors over the course of their lives, similar to the tags in your pet dog or cat. Researchers use a special reader or antenna in the creek to scan the fish and record the unique tag number. Scanning the fish helps researchers learn more about how they grow and their time spent in fresh versus saltwater. In any given sampling year, CDFW staff and partners tag between 400 and 800 juvenile steelhead.

In conjunction with work by RCD to reconnect Butano Creek, CalTrout, Trout Unlimited, CDFW, and the RCD were able to expand on these restoration and monitoring efforts with the installation of our PIT tag detection arrays: one located on Pescadero Creek, where we stand today, and one on Butano Creek. Now both tributaries to the marsh have antennas so we can determine the proportion of fish relying upon each for spawning and rearing.

How does the detection array work?

The detection arrays utilize swim-over antennas and consist of two flat PVC grids that span the length of the entire channel. The fish tags contain a radio transponder which reacts to the electromagnetic charge in the antennas supplied by batteries on the bank. When a tagged fish swims over the antennas, this reaction sends a message to the computer and the unique tag number of the fish is recorded for researchers to examine in near real-time from their desktops. Additionally, each fish has a unique tag ID number, giving the computer information it needs to differentiate between fish. We can identify which direction the fish is swimming because there are two antennas: if a fish swims over the downstream antenna first, followed by the upstream antenna, we can determine that the fish is traveling upstream. Understanding which direction a fish is traveling is important because it can give us a hint to that fish’s behavior. For example, a fish traveling upstream may be on its way to spawn, while a fish traveling downstream may be traveling back to the ocean after spawning or may be a juvenile fish that has spent time rearing in freshwater and is now ready to feed in the food-rich marsh habitat before migrating back out to the Pacific.

This technology is especially useful because staff do not need to be in the field to receive or analyze this information. The reader board, located in the field, receives the readings for each unique fish tag ID. Since the reader board is connected to a modem, the information can be easily translated to other computers. Project partners and researchers receive near real-time updates on salmon and steelhead passing the antennas on both Pescadero and Butano creeks. This new state of the art equipment was funded by San Mateo RCD’s grant from NOAA Restoration Center.

In the Redwoods, Hunting for Redds

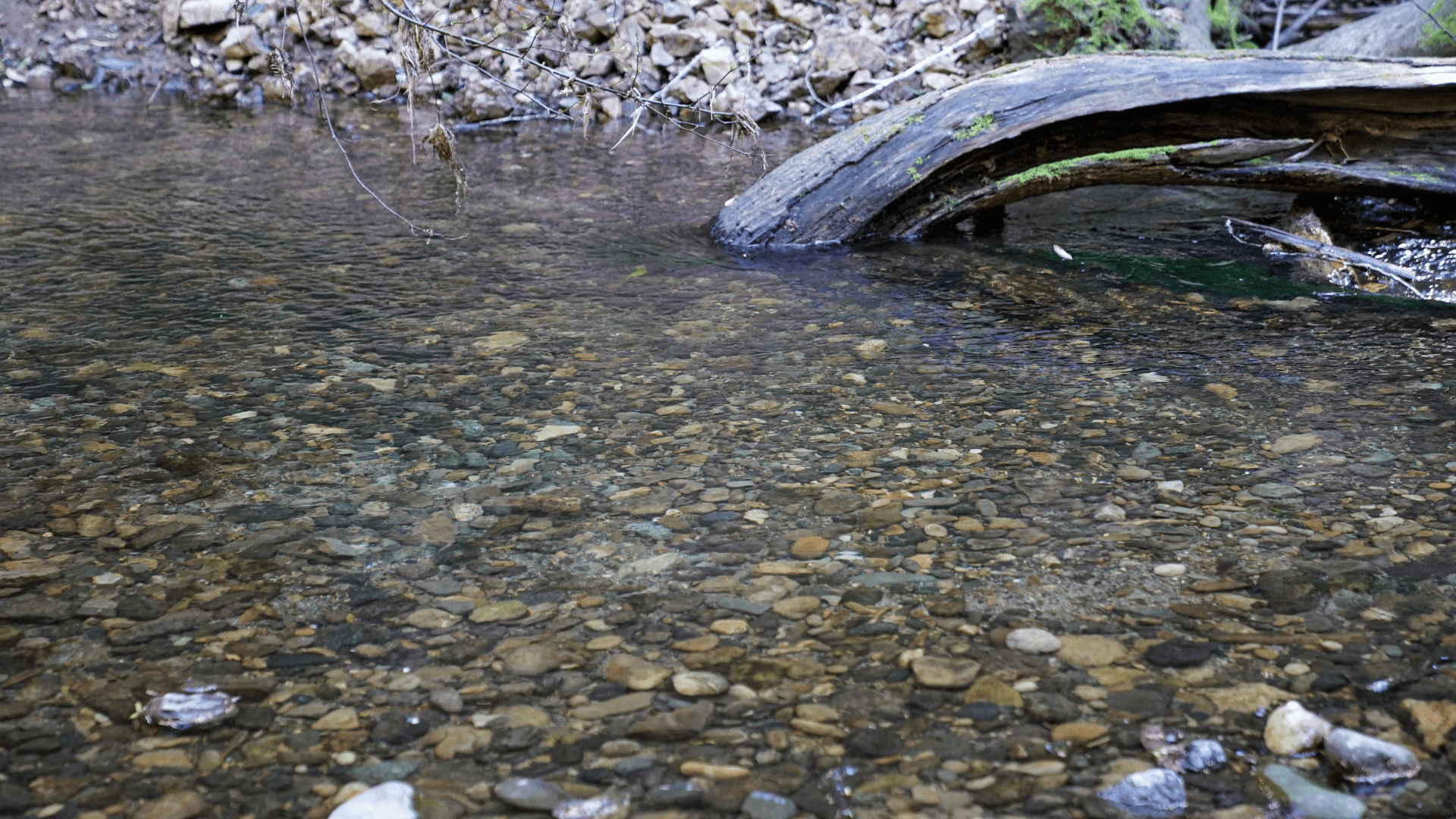

Our final stop is in the cool shade of the redwoods. We are in Memorial Park in Loma Mar, surrounded by towering tree giants, tall enough to humble you, and we are on the hunt for redds.

Sean Cochran of CDFW leads us down to the water’s edge in the park to examine redds he and his crew have observed and recorded just days before during their weekly surveys. When salmon and steelhead spawn, the female fish digs out the redd, and as she spawns with the male, she lays her eggs, working her way up as she covers them with rocks. On the downstream side, you can notice a pile up of cleaner looking gravels. This is the tail of the redd and the place where the embryo of that fish’s offspring is developing, buried beneath the gravel. This transitions into a divot which indicates the pit of the redd. From the creek’s banks, we are lucky enough to see a coho salmon redd from these critically-endangered fish right here in the Bay Area, and to contrast that with the more common redds from steelhead seen nearby.

It is incredible thinking about the journey these fish make and the trials they must face. From the turbulent ocean waters to an estuary once choked with oxygen deficient waters, they travel miles upstream, gaining extensive elevation, until they reach their spawning grounds in this sacred place.

This is my first time seeing a CalTrout project in the field, and a feeling stayed with me throughout the tour, as we traveled from ocean to redwoods. I cannot help but think about how distinct this experience is. It’s one thing to read about one of these projects on our website. It is a whole other thing though to be here, on this land, breathing in the air of this place and seeing it with my own eyes. It is a feeling I am sure many of our supporters share today — a glimpse at the beauty of the ecosystems that need protection and the progress that has been made towards that protection. This is where our combined hard work culminates. All of us- donors, staff, board members, and the rest of the CalTrout community- standing on the very land that we are working so hard to protect.

Collaboration in Conservation

These partners working together in Pescadero is a textbook example of the collaboration in conservation model that CalTrout follows throughout all our work across the state. CalTrout’s work to monitor these fish populations in Pescadero would not be possible without the hard work of our partners to tag these fish and restore their habitats — and nor would their work be as informed or meaningful without our contributions. Collaboration is essential to CalTrout, and we strive to engage with partners and communities through all our projects across California. Our work in Pescadero is also almost entirely privately funded, and your contributions have made this progress possible and helped build momentum for the kind of monitoring that is necessary for understanding steelhead population dynamics, habitat recolonization of Pescadero and Butano creeks by coho salmon, and informing future management and restoration.