by Carson Jeffres,

UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences Senior Researcher

Tracking Genetics in the Fall River

The Fall River, a hidden gem in Northern California, is one of the streams that provides reliable cool water during the warm summer months, even during the extreme 2012-2016 drought in California.

These streams are fed by extensive, long duration aquifers that produce reliably cool flows throughout the summer.

However, critical habitats for cold-water species are anticipated to disappear as global climate change raises stream temperature during hot summer months.

Disappearing cold water will result in reduced populations of trout and salmon impacting the cultures and economy that depend on them.

The UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences (CWS) in partnership with Cal Trout and the Fall River Conservancy have been studying the rainbow trout population of the Fall River since 2013 to better understand how the Fall River functions as a cold water refuge for this important fishery.

Carson Jeffres. Photo: Val Atkinson

Unusual Spawning in September

In 2012 researchers at CWS noticed an unusual thing happening in the Fall River. Rainbow trout were spawning in September.

This is highly unusual for rainbow trout as they are generally thought to spawn in the late winter and spring months generally coinciding with the spring snowmelt.

This observation started what has become a seven year study that has led to a better understanding of Fall River rainbow trout and also led to the development of a new technique in genetics that is being used for conservation studies ranging from plants to elephants.

All of this information evolved from a single observation and an ideal living laboratory into a study about an amazing fish.

Fall River Rainbow Trout. Photo: Val Atkinson

Hatching a Study

After this fortunate observation, an idea was hatched about how we could possibly study this unique population of rainbow trout.

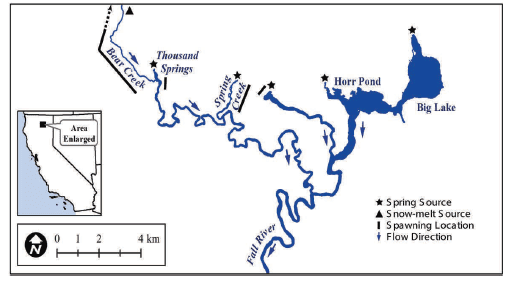

During the summer months, the source of the Fall River is found in a complex of springs near the confluence of Bear Creek.

Bear Creek is a seasonal creek that can run very high during the winter months and is dry during the summer in the lower few miles above where it meets the Fall River.

These two streams have very different characteristics, Bear Creek has high variability in stream flow and temperature while the Fall River maintains steady flow and temperature throughout the year.

From observations in previous years, there is a large population of fish that run up Bear Creek to spawn with the young of the year juveniles returning to the Fall River in the spring months.

This a pattern similar to steelhead and salmon leaving the ocean to return to the rivers to spawn, with the juveniles returning to the ocean the following spring.

This immediately brought up the question, do the same fish that use the highly variable Bear Creek alsouse the stable spring-fed Fall River?

Overview of Fall River tributaries and rainbow trout spawning areas. (Ali et al. 2016)

Collecting Samples for the Study

This question about how fish use these two very different streams led to the project that began in 2013.

To answer this question, we began collecting fish with our partners at California Department of Fish and Wildlife Wild and Heritage Trout Program in the lower Fall River and taking a genetic sample as well as implanting a passive integrated transmitter (PIT) tag into the abdomen of the fish.

The genetic sample is a small fin clip from the tail, smaller than the size of a pencil eraser that will grow back as the fish continues to grow.

Scientists take fin clipping as genetic sample. Photo: Val Atkinson

The small PIT tag, about the size of a grain of rice, is identical to those that we put into our pets as an identification marker. The PIT tag is also the same technology that allows FasTrak to work in the Bay Area in northern California.

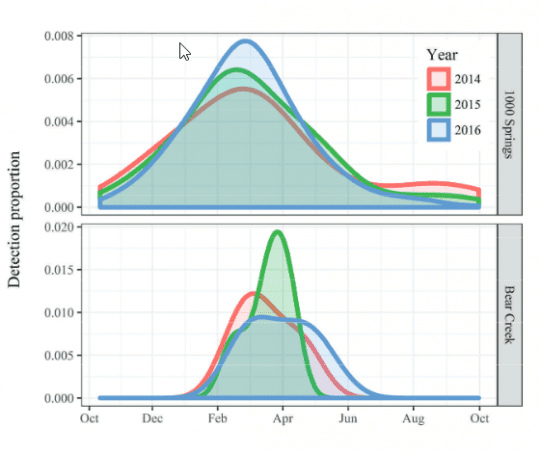

We also constructed a series of antenna stations near the springs source in Fall River as well as in Bear Creek that records every time that a specific fish with a tag passes through the antenna station.

Basically, the tag we put in the fish is like the small FasTrak box that you have in your car and the antenna is the toll plaza that records when you pass.

As of April, 2019, we have tagged a total of 3,354 fish with more than 1 million detections at the antenna stations.

Inserting a passive integrated transmitter (PIT) tag into the abdomen of the fish. This will track the migration movement of the fish. Photo: Val Atkinson

FasTrak

What We Learned

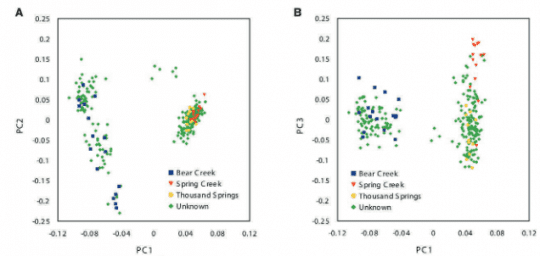

With the combination of genetic data and location where the fish go spawn, we were able to determine that there are two distinctly different populations of trout in the Fall River, one that spawns in Bear Creek and one that spawns near the springs.

We were also able to document how spawning migrations differ between the two populations, the Bear Creek population all migrates during a narrow time window in late winter, while the majority of the Fall River population spawns around the same time as Bear Creek, the timing of spawning is much more spread out starting in September and continuing through June.

When we started sampling in 2012 there were two very distinct populations of fish in Fall River meaning that despite living side by side in the main Fall River, there was essentially no genetic overlap between the two populations.

As the drought progressed and Bear Creek ran low and at times did not run at all, the conservation potential of the Fall River was put to the test.

Bear Creek’s high susceptibility to the drought was analogous to streams throughout California where entire brood years of trout populations were threatened with low flows and high temperatures.

The Fall River, meanwhile, maintained cool temperatures and stable flows and effectively buffered the Fall River rainbow trout fishery from a dramatic crash by offering refuge.

With the continued genetic sampling, we were able to observe that while there were some hybrids (Bear Creek X Spring-fed fish) that started to show up near the end of the drought, in general, the Bear Creek genetic population made it through the drought still genetically distinct by utilizing the stability of the spring-fed Fall River.

The spring-fed Fall River is a very special place, as I imagine that anyone who has spent time there has similar feelings.

Through this collaborative project between CWS, Cal Trout, Fall River Conservancy, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, private land owners, guides, and other people who love the Fall River, we were able to highlight not only is the Fall River a beautiful place with abundant hatches and amazing trout, but it is also a location that is critically important to conserve as a cold water resource as we see the effects of climate change starting to creep into the rivers and streams that we love.

Resources:

Fall River Rainbow Trout Migration Project - April 2018 Update

Photo: Val Atkinson