Southern California Steelhead

"Steelhead in Southern California……What?!?!" That’s the most common reaction when someone mentions steelhead and Southern California in the same sentence. Most people think of steelhead as only being in Northern California and along the west coast into Canada and Alaska. They are always associated with being a coldwater fish and cold water usually isn’t associated with SoCal. When I started hearing rumors of giant steelhead as far south as San Diego, I must admit my curiosity peaked.

I refused to believe they were real steelhead and dismissed the stories as merely rainbow trout trapped in small creeks and rivers being called steelhead. But the non-profit I work for, California Trout, began to consider an office in Southern California, solely to protect these fish. Then a friend showed me a photo of a chrome bright 30-inch fish from the Santa Clara River. That was all it took, I had to go down there and explore these rumors and stories and investigate this phenomenon for myself.

Steelhead Redd. Photo: Mike Wier

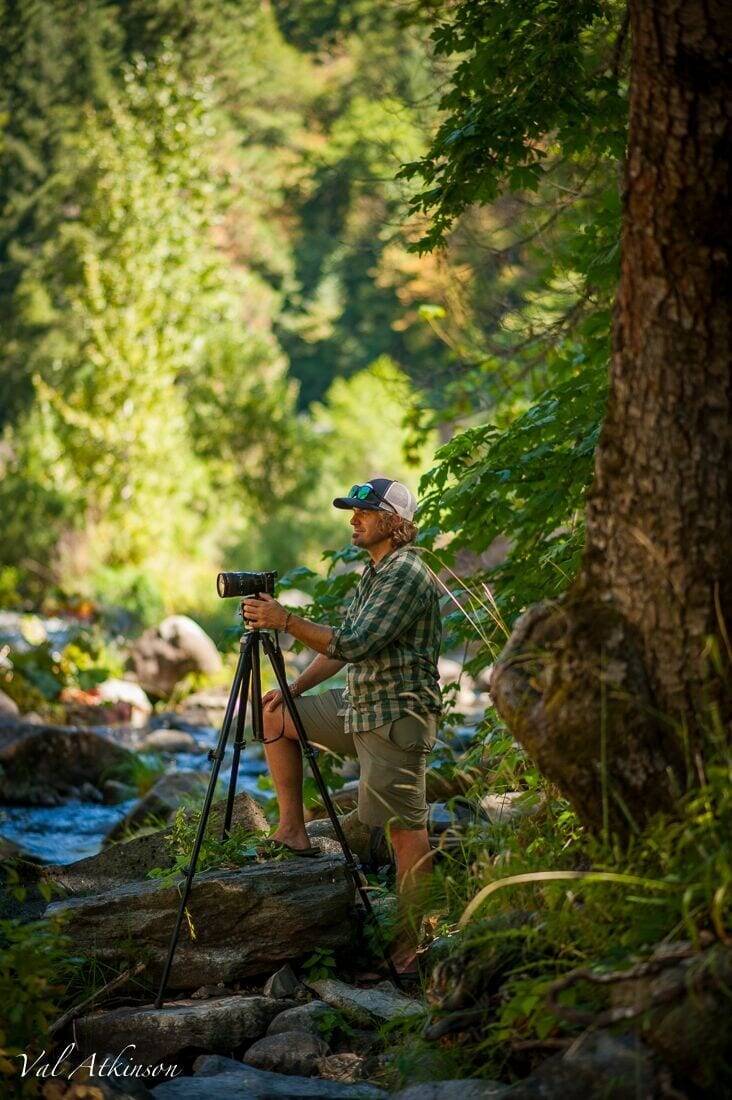

First, I’m an angler. My discipline is fly-fishing. I’m dedicated to the point of obsession.

I know some anglers believe that, when it comes to fish, if you can’t catch it, it’s not worth caring about. But the wildlife lover and conservationist in me maintains a curiosity that extends past angling.

I believe true fisherman have a desire to know about all kinds of fish and wildlife. And of all the fish I’ve come across in my travels, few are dearer to my heart than the Pacific steelhead.

Not only are they one of the most revered game fish, ecologically, they are also one of the most badass fish on this planet.

Part of my job with CalTrout is producing multimedia stories to help promote some of the conservation efforts we are engaged in. I was asked to make one such story about the Southern California steelhead.

My first stop was at the office of Mark Capelli, a fisheries biologist for NOAA working out of Santa Barbara. Capelli helped write the recovery plan for Southern California steelhead and is an expert on these fish. The first thing I noticed as I entered his office was an old photograph of a large adult steelhead sitting on the bank of a river. Mark said the specimen was pulled from the Ventura River just a few years ago.

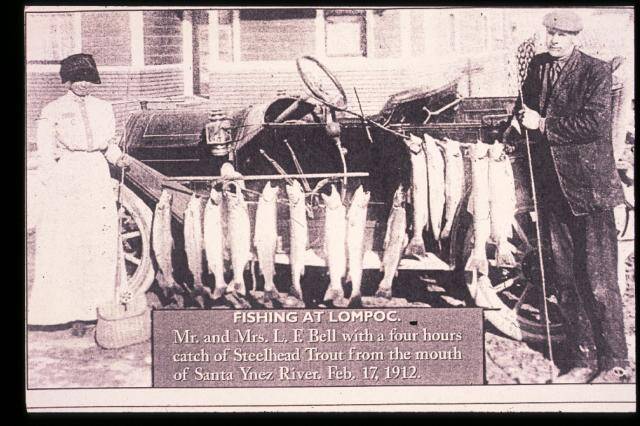

The fish was more than 30 inches and probably would’ve fought like hell if hooked on a fly rod. Mark went on to tell me about the history of steelhead and angling in Southern California. He produced several images dating back to the early 1900s of large steelhead from just about every river flowing into the ocean from the Santa Ynez to the Los Angeles River.

“The steelhead in Southern California occupied nearly ever watershed in Southern California and there’s several thousand miles of stream habitat,” Capelli said. “Trout and steelhead angling in Southern California was a major recreational activity with significant economic implications leading right up to the 1950 and the completion of the major Dams.”

The story of known human interaction with steelhead starts with the Chumash people, a tribe indigenous to the South Coast. For thousands of years they coexisted with the fish, which they fondly called “Isha’kowoch” and harvested from the rivers during their annual runs in the winter months.

The Chumash had dances and prayers to honor the fish. As immigrants from Mexico and Spain then European’s and 49ers populated Southern California the word of these magnificent creatures began to spread. By the early 1900’s they had become a popular game fish.

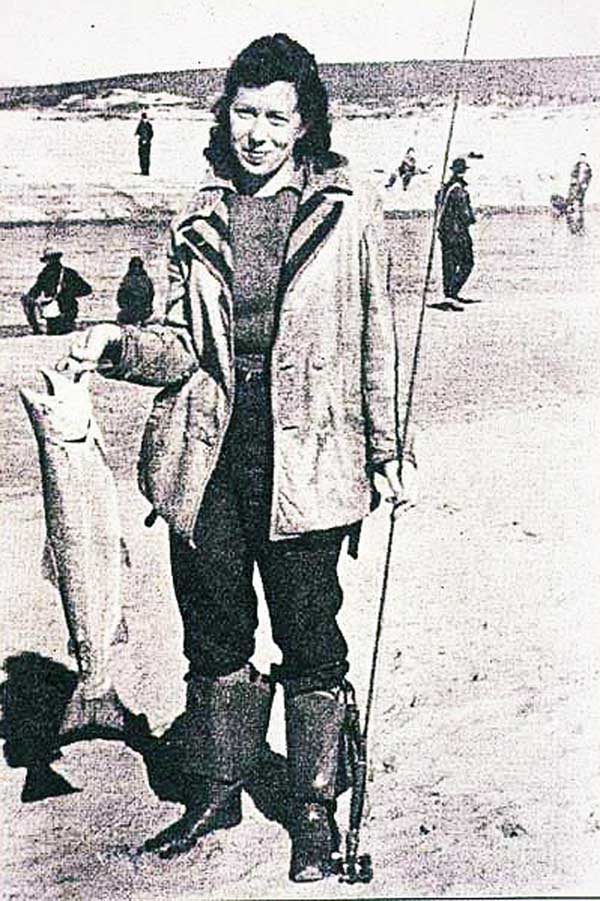

People from far and wide would flock to the rivers from Jan-March to fish for giant steelhead. There were no salmon that far south so steelhead became the game fish of choice for So Cal. There are many historical photos taken during this era that depict angling for fish well over 30 inches.

Santa Ynez River Steelhead c. 1920

Santa Ynez River Mouth Steelhead c. 1942

By the mid 1940’s the age of dams had caught up with the southern part of the state.

Walls of concrete trapped many of Southern California’s major rivers cutting off these fish from miles of their historic spawning and rearing habitat.

Water was diverted from rivers for municipalities and ag usage. Concrete diversions, Arizona crossings, culverts at road crossings and altered stream channels began to create a landscape that fish could no longer recognize or fully utilize. As a result, the populations began to precipitously decline.

Just about everything one could do to disrupt a river had been done to the rivers in Southern California. Unlike many of the rivers up north that were known for large runs of Salmon, most of the dams down south didn’t come with mitigation programs that included a hatchery.

This ultimately may be one of the main factors contributing to the fact that somehow, against all odds, wild Southern California steelhead continue to persist.

Photo: Matilija Dam

Southern California steelhead are statistically the most endangered native fish in America. In the early 1900s hundreds of thousands of them returned to the rivers between San Louis Obispo and Mexico. Now, there are reportedly under a few hundred adults returning annually.

Thankfully they are also one of the most adaptable fish on this planet. These subsets of steelhead can withstand the highest range of temperatures of any other salmonid on earth. Here in southern California these fish are subjected to huge variances year to year of flows, sediment loads, water temps, wild fire effects, pollution and other negative environmental factors.

Because there are few hatcheries on these systems many of these runs of fish have maintained their wild and native genetics. It is this fact that has helped this fish press on to make use of the habitat that remains as well as adapt to environmental factors such as climate change.

“In a way, Southern California Steelhead should not exist. Here we have these fish that are going out to sea and returning to these streams that are heavenly urbanized,” said Peter Moyle, a leading fisheries biologist with University of California Davis Center of Watershed Sciences. “Everything you can imagine that can be done to a stream has been done to the streams in Southern California and yet they keep coming back year after year.”

The thing that stood out to me the most about these fish is their ability to display and act on choices in their stages of life history. Say there is a big water year and a pair of wild steelhead enter the Ventura River. Those fish spawn in a matter of just a few days and can potentially lay more than 1000 eggs.

Once those eggs hatch those fry have decisions to make, unlike salmon where most to all the fry will display a similar life history and just begin to move down river towards the ocean in a school. So, say half the eggs laid decide to head up river and rear in cold shaded pools far up in the canyon.

The other half of those fry may decide to head down river and rear in the brackish estuary or lagoon area where the river meets the beach. Then next year when a big storm comes, some of those fry will head down to the ocean to become steelhead. Others will stay in the river.

Studies show that sometimes the fry in the estuary will head up river and settle in the remote head waters. And sometimes the fish that were very high up in the system might come down and try the estuary for a while. Some will go to the ocean the next season and some will stay in the river their whole life.

On the same token, adult fish returning from the ocean may find unfavorable conditions in their stream of birth. They can then choose to look for another river up or down the coast with better conditions or just go ahead and stay in the ocean for another year and try again the next season. It’s these choices that give this species such a high chance of survival.

Steelhead Redd. Photo: Mike Wier

Suppose something happens in the headwaters that year like a mudslide or chemical spill. It may wipe out all the fish in that upper stretch.

But since there may still fish in the estuary that strain will most likely survive. Or if something happens lower in the system then the upper population survives and can move back down once conditions improve. Or say something happened in the river and all the rainbows were killed.

It only takes two fish from the ocean of that strain to repopulate the river again with smolt the next season. In this way, these fish have managed to survive and continue in persist in conditions far less than favorable.

Photo: Santa Clara Estuary

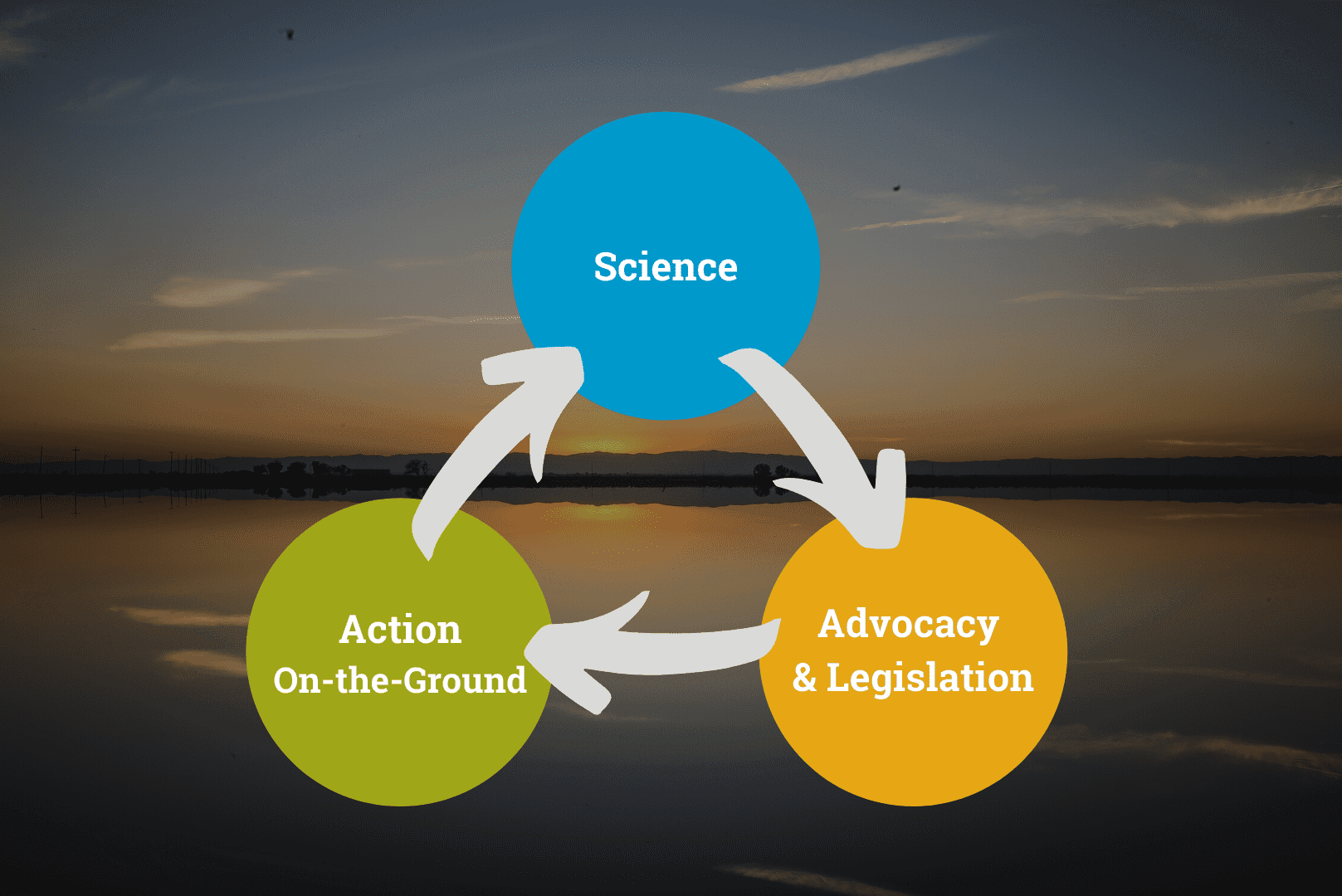

Luckily more and more are becoming known about this strain of steelhead. The more we study them, the more we know about their movements and cycles of life history.

This data is helping make management decisions that could help allow these fish to coexist with our changing landscape. But now is the time to implement these changes.

We are on the precipice of extinction. As climate change begins to affect California more and more, the genetics of these fish will become more and more valuable. As rivers up north become warmer and more urbanized it’s the genetics of these wild steelhead that will be the future of salmonids. We can’t rely on hatcheries. We must have stocks of wild fish that can choose their own mates and make their own adaptations.

For more about Southern California Steelhead visit CalTrout.org and watch the documentaries:

- Southern California Steelhead: Against All Odds

- Santa Clara River: Restoring Resilience

- Santa Margarita River Recovery

- Mike E. Wier, CalTrout Field Reporter