Written by

|

|

The California Environmental Flows Framework

One of the major factors affecting the decline of salmonids in California is insufficient streamflow. Streamflow has been referred to as the ‘master variable’ because it controls so many different aspects of the aquatic environment. For example, it strongly influences large wood and sediment recruitment, key contributors to habitat forming processes for salmonids and other native fishes.

It also cues specific life history events such as juvenile and adult fish migrations, behavior, and, more recently, has been shown to influence the relative success of introduced or invasive species (more on this later).

Changes in streamflow can also strongly affect water quality, including temperature, but also aquatic food webs. Not surprisingly, flow alterations are therefore a significant driver of salmonid population declines throughout California and elsewhere. One of the major questions fish biologists are often asked is “how much water do fish need?”

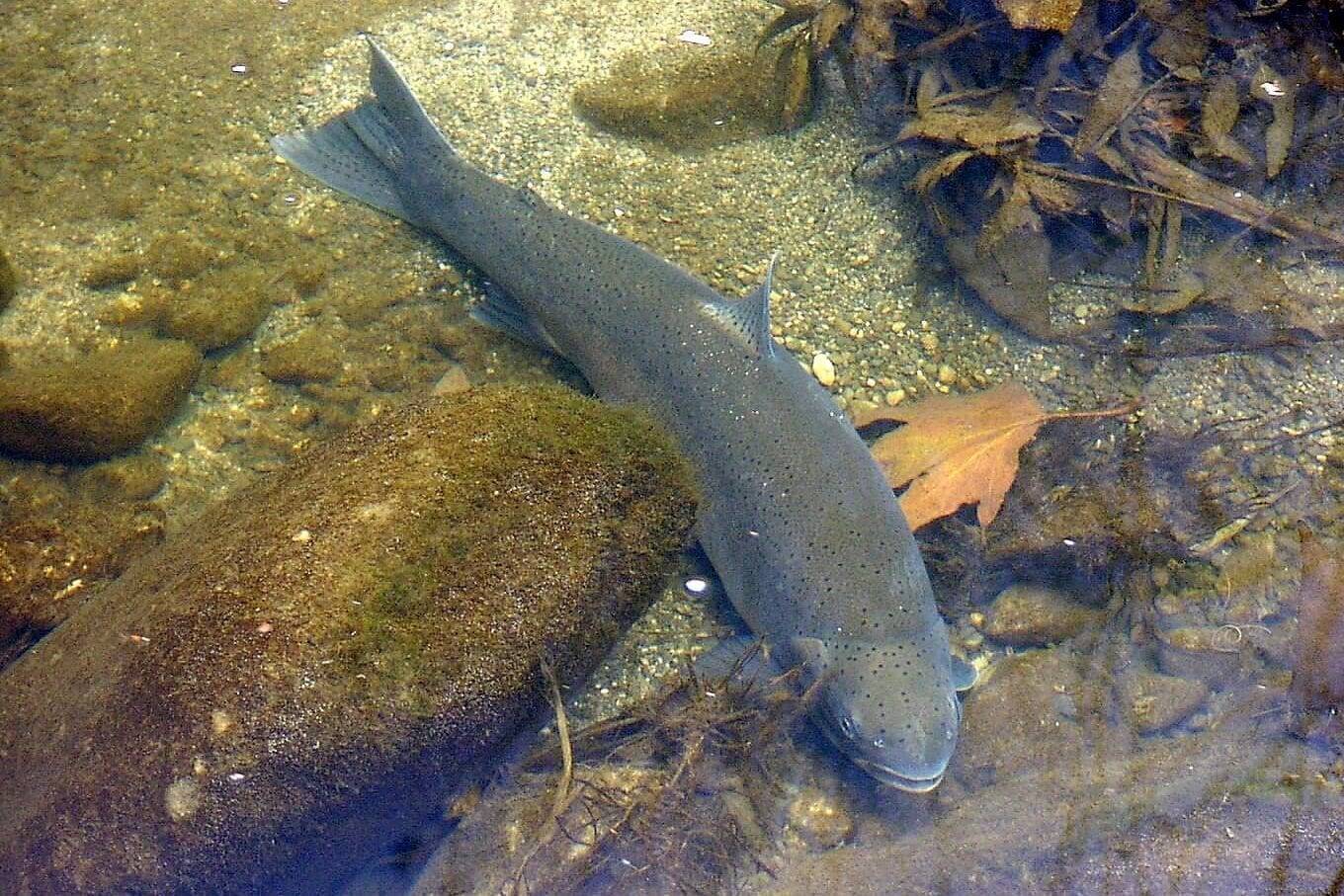

Cover photo: Kent Blackburn

Photo: Wendy Lu

In 2016, a group of scientists from California Trout, UC Davis, UC Berkeley, The Nature Conservancy, Utah State University and the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, with funding in partnership from the State Water Board, began to delve into this question and others.

They formed what is collectively known as the California Environmental Flows Framework (CEFF or the Framework) which, ultimately, seeks to determine ecological flow criteria for native fishes and other aquatic species throughout the state, which can be used to inform the development of environmental flow prescriptions.

The question of “how much water do fish need?” is a difficult one due to California’s diverse geography and fish communities, which are further complicated by numerous micro-climates and management goals of different agencies.

To deal with these complexities, the Framework provides guidance on how to determine environmental flows and, thus, better define how much water fish need.

Photo: Glenn Kubacki

What are Ecological Flows?

Ecological flows seek to understand key linkages between streamflow and biological response.

If these linkages can be defined, then we can begin to piece together a flow regime that can be used to support native species.

Yet streamflow is affected by numerous factors, and numerous methods exist to quantify relationships between streamflow and biological response.

For the past several decades, most of the instream flow literature, as well as guidance from federal and state agencies, has examined how changes in flow were correlated with shifts in depth and velocity, particularly during key periods (e.g., spawning or rearing).

The thinking here was that if sufficient depth and velocity existed then sufficient habitat would exist and contribute to species recovery.

However, we now know that habitat, from a fish’s perspective, goes far beyond just depth and velocity preferences and that streamflow and the full life history of salmonids are inextricably linked.

So, instead, CEFF uses a functional flows approach to better understand how much water fish need and, importantly, when they need it.

Photo: Chris Bradley

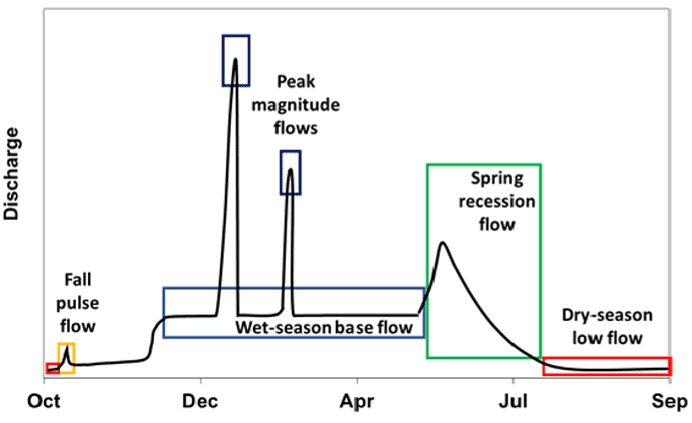

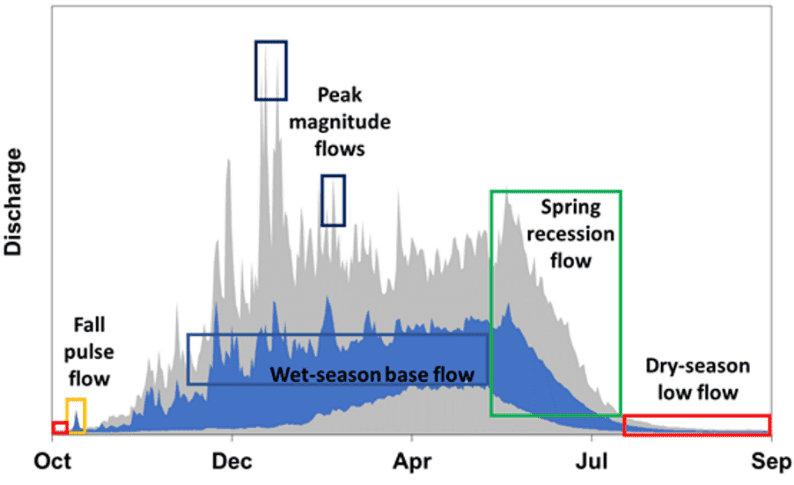

Figure 1. A natural hydrograph (flow regime) of a river in California showing 90th and 10th percentiles (grey shaded area) and mean daily discharge (blue shaded area). Functional flow components of the hydrograph are highlighted as boxes including a fall pulse flow, peak magnitude flows, a wet-season base flow, a spring recession flow, and dry-season low flow.

What are Functional Flows?

Functional flows, as defined by Yarnell et al. (2015, 2020), are components of the hydrograph that provide distinct geomorphic, biogeochemical, or ecological functions (Figure 1).

The functional flows approach provides a basis for estimating how much water is needed for the environment, where key components of the natural flow regime are targeted rather than the entire natural flow regime.

Desirable functional flow components have a disproportionally important role in supporting the physical and ecological processes that create and maintain habitat and trigger native species seasonal movements.

The Framework recognizes five distinct functional flow components including a fall pulse flow, peak magnitude flows, wet-season base flows, spring recession flows, and a dry season low flow (Figure 1).

These functional flows components, and associated characteristics (the magnitude, timing, rate of change, duration and frequency of flows) and metrics, can then be used to determine flow criteria at various scales and levels of detail for rivers and streams throughout California.

Instead of implementing an entire natural hydrograph, which may be unrealistic due to the numerous demands on freshwater in a basin, a functional flow hydrograph can be used (Figure 2).

This means that during certain, ecologically or geomorphically important periods, particular flows will be necessary to improve ecosystem health (i.e., summer base flows to provide cold-water during over-summering or a spring recession flow to improve juvenile salmon outmigration).

It also means that there are other periods when flows are less important, providing more flexibility for water supply and demand.

Functional Flows in Practice

The science behind functional flows is relatively new, but strong empirical evidence exists to suggest that implementation of this approach works for salmonids and other native fishes.

Putah Creek, a Central Valley stream that historically supported fall-run Chinook and other native fishes, was a testing ground for the functional flows hypothesis.

While this long-term experiment predated the term “functional flow”, the same guiding principles were applied to establish a flow regime that encouraged native fish recovery after diversions and drought had wreaked havoc on the ecosystem during the early 1990s.

Specifically, Kiernan et al. (2012) found that implementation of certain flows including a fall pulse flow, spring spawning or recession flows, and summer base flows strongly affected the fish community, shifting it from one dominated by non-native fishes to a community dominated by native fishes.

More recently, Putah Creek has also experienced a strong resurgence in its fall-run Chinook population (see Moyle et al. 2017).

Photo: Klamath River by Mike Wier

Aside from the technical aspects of establishing flow criteria for streams and rivers throughout California, CEFF also recognizes that multiple state and local agencies across California share responsibility for setting flow criteria that protect California’s water resources.

These approaches historically have not been coordinated at the statewide level, resulting in fragmented and siloed flow management programs.

As such, an important policy component of the Framework is the formally adopted California Environmental Flows Workgroup, which is officially recognized by the State of California Water Quality Monitoring Council.

Quarterly meetings are open to the public and are attended by both federal and state agencies not just for technical updates, but also as an opportunity to provide feedback to the technical group.

We see this marriage of science and policy as fundamental step in setting environmental flow criteria for all streams in California.

Dr. Robert Lusardi is the California Trout-UC Davis Wild and Coldwater Fish Scientist and Dr. Sarah Yarnell is a senior researcher at the Center for Watershed Sciences, UC Davis. For more information on the CEFF, pleases visit https://ceff.sf.ucdavis.edu/

Literature Cited

Kiernan, J. D., Moyle, P. B., and Crain, P. K. 2012. Restoring native fish assemblages to a regulated California stream using the natural flow regime concept. Ecological Applications 22(5): 1472-1482.

Moyle, P. B., Lusardi, R. A., Samuel, P. J., and J. V. E. Katz. 2017. State of the salmonids: status of California’s emblematic fishes 2017. A report commissioned by California Trout. 579 pp.

Yarnell, S.M., Stein, E.D., Webb, J.A., Grantham, T., Lusardi, R.A., Zimmerman, J., Peek, R.A., Lane, B.A., Howard, J., and Sandoval-Solis, S. A functional flows approach to selecting ecologically relevant flow metrics for environmental flow applications. River Res Applic. 2020; 1– 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3575

Yarnell, S. M., Petts, G. E., Schmidt, J. C., Whipple, A. A., Beller, E. E., Dahm, C. N., Goodwin, P., and Viers, J. H. 2015. Functional Flows in modified riverscapes: hydrographs, habitats, and opportunities. Bioscience 65(10): 963-972.