By Craig Ballenger

CalTrout Fly Fishing Ambassador

Lewis MacAdams and the Los Angeles River

During the winter of 1815, the Los Angeles (LA) River washed away the original Pueblo Plaza. Again in 1825 floods returned, churning away woodlands downstream from the Pueblo and slashing a ‘new’ route draining marshlands of the river’s estuary as it emptied into the Pacific Ocean.

Back in 1790, the Los Angeles Pueblo was home to around 140 Spanish. Within 10 years, that population had more than doubled to 315. Who would have believed the population of LA could double in 10 years? We can look even further back for trends and disturbing observations.

Geologists suggest the rise of the San Gabriel Mountains to over 10,000 ft began occurring around 100 million years ago. Later to rise were the Simi Hills and the Santa Monica’s. Rainwater drained mostly south from Big and Little Tujunga Canyons. Over time, a Lake was formed, today’s San Fernando Valley. Finally, a breach was cut through what is today called the Glendale Narrows, draining the lake and forming a river.

The Tongva Tribe had called this region home for thousands of years. Linguistically Shoshone, they were renowned for basketry and soapstone carvings. The Tongva (more commonly known by their Spanish name of the Gabrielino) lived by hunting, fishing, and harvesting abundant acorns along the river corridor. They are estimated to have had around 45 villages along the stream.

However, their world changed forever when dusty travelers wandered out of the south, heading up the coast during August of 1769. They were riding large mammals, searching for Monterey Bay, discovered 150 years earlier. They totally missed it, discovering San Francisco Bay further north instead.

Photo: San Gabriel Mountains by Chris Heald.

Led by Gaspar de Portola and accompanied by Padre Junipero Serra, expedition diarist Fray Juan Crespi penned the first description of the LA River:

“August 2nd, we set off from the valley in the morning (they had camped at Arroyo Seco near modern day Sycamore Grove the precious night) and followed the same plain in a westerly direction. After traveling about a league and a half through a pass between low hills, we entered a spacious valley, well grown with cottonwoods and alders, among which ran a beautiful river from the north northwest, and then doubling the point of a steep hill, went on afterward to the south.”

It was a sacred holiday, “for the great indulgence of our Lady of Los Angeles de Porciunula.” Thus, the river was named by Franciscan monks the Porciuncula. They camped around where Broadway crosses the river. In a classic foreshadowing which would have made Hollywood proud, Crespi noted the valley was fertile, with abundant wild grapes and (he thought) an ideal spot for a settlement.

Further, he noted, near the confluence of Arroyo Seco and the river, “this dry bed unites with the river giving clear indication of great floods in the rainy season, for we saw that it had trunks of trees on the banks...here we felt three consecutive earthquakes in the afternoon and night.”

Hmm, nice spot for a Pueblo, signs of past floods, three earthquakes in a day. What could go wrong? Father Serra decided to build the mission at San Gabriel, on the next river south, in 1771. The civilian village, originally of 44 people from eleven families was founded 10 years later, based on this contemporary observation: “three leagues from that mission (San Gabriel) is found the Rio Porciucula, with much water easy to take on either bank and beautiful lands in which it can all be made use of.”

During that first year, the original ditch, or waterway, was dug from below a weir constructed on the river, providing domestic and agricultural supplies. Curiously, the original San Gabriel Mission site downstream was flooded just five years later, resulting in the mission being rebuilt on higher ground.

As the Pueblo prospered (in the Spanish and the later Mexican pre gold rush era sense), the river’s bounty seemed to become less than ample, and groundwater wells were dug upstream from 15-25 feet deep. Soon that too was exceeded and water collected in a small reservoir above the Burbank Narrows.

By 1854, with a burgeoning population, the first water overseer was commissioned, distributing irrigation and drinking supplies as the aquifer began to recede. During the floods of 1861-62, fifty inches of rain fell in five weeks, flooding most of the old lakebed of the San Fernando Valley. This was followed by years of drought, then back to winters of flood. And so, it goes.

Photo: San Fernando Valley by DailyNews, SCNG

By 1900, the population of Los Angeles County had easily surpassed 100,000. And it kept growing. The reality was irresistible, more people than water on one hand, and a rebellious river that needed to be tamed on the other. A classic conundrum! Enter William Mulholland, the infamous water superintendent who sold Angelenos on the Owens River Aqueduct in 1904. By 1913 all 300 plus miles of it was online, and Mulholland’s speech as the Owens flowed forth into the San Fernando Valley concluded to an exuberant public and press, “There it is, take it.!”

One year later, the LA River flooded again. But by now, Angelenos’ imbedded boosterism saw no water challenge as too large. And so, plans were developed to channelize Crespi’s “beautiful river, lined with cottonwoods and alder.” By 1920, the county’s population was knocking on the door of a million. The massive floods of 1934 and 37 brought 40 and 49 deaths in the La Cresenta area. Within a few years, Crespi’s river was lined in concrete. The river appeared to be gone.

1974 brought a fictionalized version of the LA River saga to the silver screen, with Roman Polanski’s Chinatown. Now, in the fading decades of the Angelenos’ exuberant century, a beatnik poet showed up at a concrete rim and peered over into a forgotten olfactory flood plain channel.

Stage left, poet Lewis MacAdams saunters in, ponders the concrete mess, and scratches his head. His vision was no John Muir apostle crying in the wilderness about Hetch Hetchy, taking up pen to describe for the public some of the grandest scenery on the planet. Instead, Lewis turned his forlorn poet’s pen to a stinky depressing bit of ancient riparian corridor relegated to a besotted water channel. Absolutely nothing aesthetic to see here, nothing to roam the eye over in wonder. Famously, he stood in the tepid water and “asked the river if he could speak for it in the human realm, and it didn’t say no.”

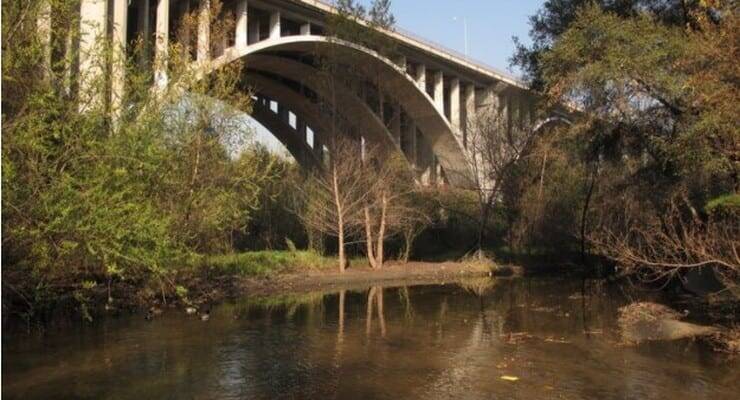

“When I saw the river for the first time, it was just a tragedy, it was so screwed up," Lewis recalled. A few years back, on a lark, I went fishing on it along a section where, between sloping concrete walls, the ancient river cobble still glistened beneath the water. Our quarry was carp, not the long-gone pacific steelhead which once ascended the river’s fifty or so mile length. We clambered down angled concrete behind Griffith Park. The I-5 danced a relentless hum of white noise as the freeway bridge spanned the river behind us. Homeless camps were tucked in the riparian willows across the channel. Scraps of orange, white, and blue plastic pitched tent-like along the banks announced someone’s digs.

“You guys fishing?” Despite the obvious (we’re packing fly rods) some local ambles toward us on a mission. Well, we’re in a city of 2.6 million, not on a steelhead coastal river up north, I noted to myself. We are about to be flimflammed by a hustler. “Twenty bucks and I’ll show you where the carp are,” he enthused.

Lewis knew where the steelhead were. In a vision deep in his head. Despite being likely one of the most messed up rivers in America, Lewis saw the ancient river. But few others did. Angelenos’ likely didn’t even know they had a river. At one of his events, he asked the public for 10,000 people to show up the next day and clean up a section. Ten showed. “If it’s not impossible, I’m not interested,” he slyly admitted, with a tongue in cheek double negative.

He dreamed of the river. “You start with the river you have, and then go to the river you wish you had.” Who, I thought, in their right mind would take on such a hopeless cause? Perhaps sadly, not me. I would simply shake my head, overwhelmed, and walk away to a tumbling Sierra snowmelt mountain stream that could use some restoration.

Photo: La River. WikiCommons

Not Lewis. From no momentum, relentless and indefatigably, over the next 30 years, he began to turn the tide. Interest slowly emerged. He began a nonprofit called Friends of the LA River. When I dropped in on him at the FOLAR office, I saw a wiry, elderly gent in a pork pie hat. I imagined the poet who spoke of his river and project as art. I mentioned my longtime interest in the beat poets. Of growing up hanging at City Lights Books on Columbus in San Francisco. Of Gregory Corso and Laurence Ferlinghetti, of Alan Ginsburg’s Howl with its iconic opening line, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,” His eyes lit up, he finished the couplet, then headed off into his own metered lines. We had a good laugh.

His argument with the talking head at LA Department of Public Works is the stuff of legends. The official called it a ‘flood control channel.’ Lewis shot back, it’s a ‘river.’ Back and forth they went, voices rising. Years of haggling, educating, and enthusing locals finally prevailed, against all odds. The Army Corps of Engineers officially designated the LA River a ‘navigable stream’ in 2008. Today there is a massive movement to restore it.

Lewis sadly passed a few weeks ago. And we ponder, did Lewis win? Will steelhead once again find their way up the LA River to spawn? While it seems impossible, the flood gates of fresh thinking make it now seem remotely possible. And while the conservation movement mourns his loss on one hand, his legacy of taking on the ‘impossible’ remains a beacon, a strength, and an enduring challenge on the other. From Crespi’s river, to flood channel, back to river. Lewis MacAdams was stubborn, had no fear, and is likely wandering the river out there somewhere, composing poetry about steelhead.