By Megan Nguyen,

Communications Associate

Science is the Foundation of our Work.

Established as a scientific leader on fish and water issues in the state, California Trout relies on research to prioritize the most impactful projects and find innovative, science-based solutions to the state’s resource issues.

CalTrout is using science-based solutions to combat climate change and return our wild fish to resilience.

Below is a look at the ways science is guiding our restoration and conservation work across the state.

CalTrout is using science-based solutions to combat climate change and return our wild fish to resilience. We hope you enjoy learning about our Science-into-Action approach.

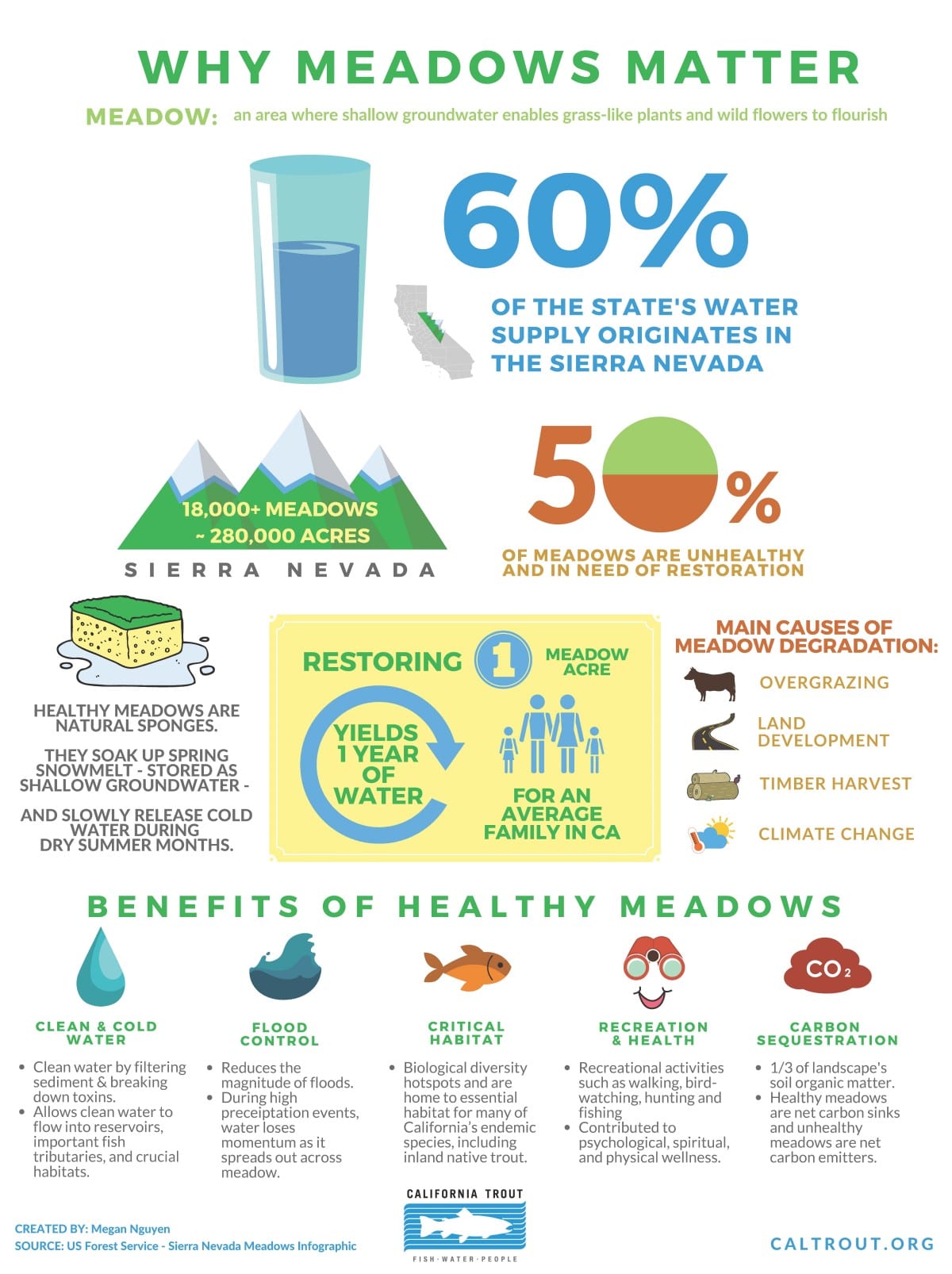

Combatting Climate Change

CalTrout is studying and restoring Sierra meadows in order to reap the natural benefits of healthy source water meadows.

Restoring meadows increases ecological resilience in the face of a changing climate, including frequency variations in rainfall and large-scale forest fires.

Sierra Meadows Partnership. CalTrout and its partners have created the Sierra Meadows Partnership to work together to elevate and coordinate meadow restoration. The Partnership’s overarching goal is to restore 30,000 acres of the estimated 90,000 acres of degraded meadows over the next 15 years. Learn more about the partnership here.

Photo: Pickel Meadow by Mike Wier

Meadows Matter Infographic by Megan Nguyen

Balancing Water for Fish and People

CalTrout is studying environmental flows and using innovative strategies to find out how much water fish need to ensure thriving populations and also balance the needs of people.

One of the major factors affecting the decline of salmonids in California is insufficient streamflow. Streamflow controls so many different aspects of the aquatic environment such as habitat-forming processes for salmonids and other native fishes.

It also cues specific life history events such as juvenile and adult fish migrations, behavior, and, more recently, has been shown to influence the relative success of introduced or invasive species.

Changes in streamflow can also strongly affect water quality, including temperature, but also aquatic food webs.

Below are two ways CalTrout is balancing the needs of fish and people using science.

Photo: "Hot Creek" by Kent Blackburn

Foodwebs and Fish

Warm waters are a threat to coldwater fish such as salmon and trout. Productive habitats like spring-fed rivers, floodplains, estuaries, and seasonal lagoons will be key links for coldwater fish like salmon and trout to cope with warmer temperatures.

Here are some ways CalTrout is using science to study productive landscapes and grow more food for fish.

Growing Fish Food on the Floodplains. CalTrout’s Fish Food on Floodplain Farm Fields is using innovative solutions to reintegrate food from the floodplain back to the river. Research shows that floodplains produce resources 150 times greater than in the river. We work with farmers to grow food on the flooded farm fields and transfer those resources back to the river where fish can access them.

Conducting Experiments in the Shasta River. Researchers reared juvenile Coho salmon in a series of enclosures within the Shasta River basin, which is a tributary to the Klamath River. They examined how natural gradients in temperature and prey availability affected summer growth rates and survival. Learn more about their study.

Photo: "Central Valley Fish Food Sampling" by Mike Wier.

Monitoring Fish Populations

Two common methods used to monitor fish populations are:

Physical Monitoring. Scientists monitor fish population abundance and movement through methods such as pit tagging, snorkel surveys, electrofishing, and sonar monitoring. These approaches can also measure the physical conditions of fish habitat including water quality, water temperature, streamflow, and gravel composition.

Genetic Analysis. Genetic analysis tells scientists a lot of about the life history of a fish. Field biologists take a small fin clip from a fish and analyze the DNA — looking for small differences in nucleotide sequence – by a molecular biological technique called single nucleotidepolymorphism (SNP) analysis. From this genetic test, we can get clues as to the level of exchange of genetic information among populations (degree of inbreeding), native or hatchery lineage, and identify related populations in the same or nearby watersheds.

Genetic isolation can arise from fish passage barriers and along with declining population numbers, and can cause genetic bottlenecks. Populations with a lack of genetic diversity causes population inbreeding making them more susceptible to environmental threats since their adaptive capacity is impaired.

Maximizing biodiversity is an effective ecological risk mitigation strategy that can help inform where conservation efforts should be focused to protect native populations.

Photo: "Fall River Fish Tagging" by Val Atkinson.

Fish Genetics

Using physical monitoring and genetic analysis to track fish populations will provide us better information for our conservation plans to protect native, wild fish. Below are two projects using genetic analysis.

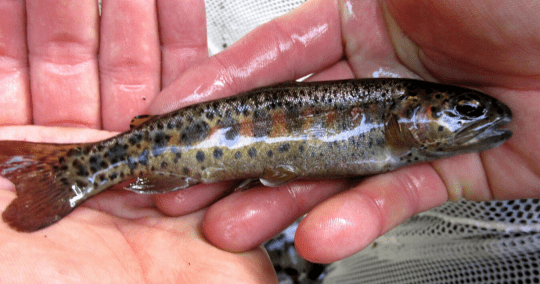

Saving the Rainbows. Southern steelhead represent the southern edge of the species’ range and are critically vulnerable to climate change. CalTrout’s project, the Native Rainbow Trout Project, will increase resiliency of native rainbow trout populations in Southern California and facilitate recovery of endangered southern steelhead.

These land-locked populations in Southern California are the remnants of steelhead runs over 100 years earlier.

They were identified by molecular genetic analysis by a study completed in 2014, and are recognized as the last remaining genetics sources of these historical salmonid populations. Learn more.

Fall River Fish Tagging. In 2012 researchers at CWS noticed an unusual thing happening in the Fall River. Rainbow trout were spawning in September.

With the combination of genetic data and location where the fish go spawn, we were able to determine that there are two distinctly different populations of trout in the Fall River, one that spawns in Bear Creek and one that spawns near the springs. Learn more.

Photo: Phil Reedy