by Corey Raffel and Jacob Katz, Ph.D.

The saying rang true when Mark Twain coined it, “Whiskey is for drinking. Water is for fighting.” 150 years later it still resonates and throughout the arid West, it is often repeated as gospel. But in California’s Central Valley an unlikely group of partners are coming together to write a new chapter in the saga of California water. Farmers, water districts, government regulators, and conservation scientists are all putting acrimony aside and getting down to business, working alongside one another to integrate a 21st century scientific understanding of how rivers work and how fish use them into farm and water management. In so doing, they are creating multiple benefits for birds, fish, farms, and people.

The Fish Food on Flooded Farm Fields program aims to help dwindling salmon populations by recreating floodplain-like wetland habitats on winter-flooded farm fields. The program works with rice farmers and water districts to intentionally inundate rice fields in the non-growing season to create the near-ideal conditions to grow the water bugs on which juvenile salmon and other fish depend on as a food source. Tons and tons of water bugs can be grown in these floodplain fields and sent into the nearby river channels where the fish are, to replenish the fish food supplies that have been dramatically reduced over the decades due to the river being disconnected from the natural floodplain.

Photo: Jacob Katz holding zooplankton (fish food) produced on the floodplains by Ezra Romero of Capitol Public Radio.

The Need for a Solution

California’s native salmon populations are struggling for survival. In its 2017 report, State of the Salmon II, CalTrout and UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences estimates that ten of the twelve California distinct salmon populations are at high or critical risk of becoming extinct in the next 50 years if current trends continue. The reasons behind the decline of salmon are complex, but we know that changes to landscapes and rivers that have reduced both flow and habitat availability are common problems for all salmon runs.

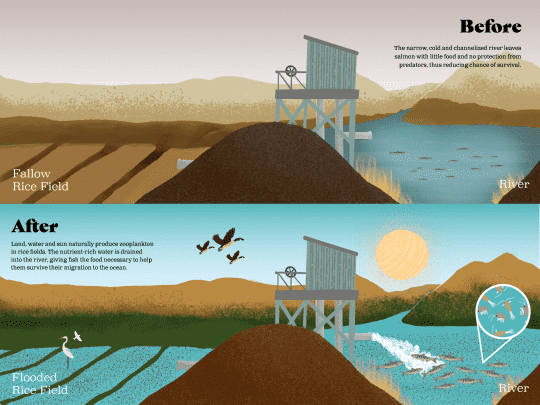

The rivers of the Central Valley of California, especially, have been dramatically modified to create the rich agricultural area it is today. Before European settlement, every rainy season rivers would swell with rain and snowmelt, overflow their banks and flood over 4 million acres of floodplain wetlands. In an attempt to control flooding and convert wetland to farmland, more than 1,600 miles of riverside levees have been built in the Valley since the goldrush. As a result, 95% of the floodplain now is cut off from rivers and is no longer inundated each winter. In addition, 20 major dams have been built to store water from the wet winters for use in the dry summers to irrigate fields but they also block salmon from migrating upstream to the majority of their native spawning grounds.

Controversies over the use of water for agriculture or for wildlife usually ended up in court and are often positioned in the press as a fight of fish vs. farms. Many such conflicts persist. But CalTrout is also cultivating a spirit of cooperation in farm country where government regulators, farmers, and conservation organizations have identified new on-farm water use practices that are good for birds, fish, and farms.

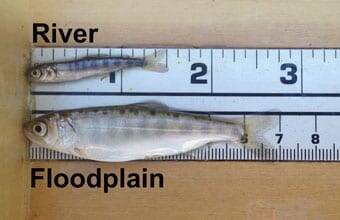

“Several years ago, the Nigiri Project studies began to show that juvenile salmon given access to shallowly flooded rice fields in winter grow at a much faster rate than do fish stuck in adjacent leveed river channels,” said lead researcher Jacob Katz, Ph.D., CalTrout’s senior scientist.

The Nigiri studies also clearly demonstrated that flooded rice fields can be an ideal place for small aquatic insects called zooplankton to grow. When juvenile salmon are given access to the zooplankton in the field, they feast on these abundant, fattening bugs and grow at dramatic rates. But, of course, wild salmon fry hatch in the rivers not in the rice fields. As mentioned earlier, the Central Valley’s rivers are now mostly separated from the rice fields that now occupy much of the historic floodplain by levees specifically designed to prevent rivers from overflowing their banks. So how do we reunite the salmon, stuck in the food-starved river channels on the "wet side" of the levee with the abundant water bug fish food that grows in floodplain farm fields on the "dry side" of the levee? Fortunately, a recently completed CalTrout study addressed this exact question.

Fish Food on Floodplain Farm Fields

What started out as a muddy puddle in the corner of a five-acre flooded rice field in 2011 has now grown into a series of landscape-scale experiments utilizing the flood and farm water infrastructure that allows the Central Valley to be among the most intensively farmed and most productive ag landscapes on Earth. “The Fish Food study expands the Nigiri Concept and shows even where fish can’t leave the river to swim to managed wetlands on floodplain farms, they can still benefit from the nearly 500,000 acres of valley rice fields,” said Katz.

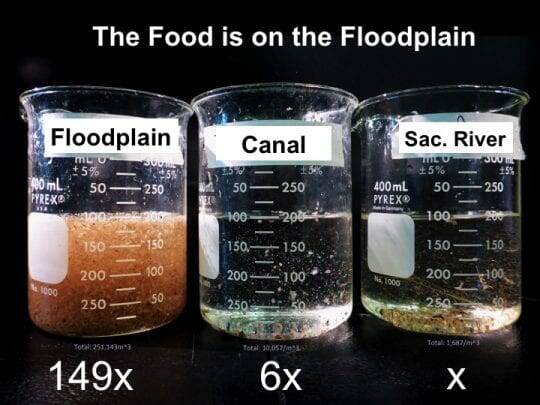

Dubbed the “Fish Food on Floodplain Farm Fields” experiment, this latest study explored the ecological impact and operational feasibility of increasing fish food supplies (i.e., increasing the abundance of zooplankton) in the Sacramento River itself. The experiment relied on existing irrigation and flood protection infrastructure to intentionally flood winter farm fields to encourage the growth of invertebrate food resources for fish. Shallowly flooded fields mimic the natural floodplain wetland conditions where algae and plant matter are consumed by microbes which in turn feed and promote the growth of small insects and crustaceans that are the main source of food for juvenile salmon.

As part of the 2018 experiment, more than 5,000 acres of farmland, owned by California Reclamation District 108 in the Colusa Basin near Knight's Landing, was flooded to a depth of about a foot in mid-November. The field was left flooded for one month to allow the food web to mature and produce the abundant zooplankton the salmon prefer. Then, over the next month, one-quarter of the fields were drained per week. The water, now dense with zooplankton, was delivered through drainage canals to the Rough and Ready Pumping Facility where it was lifted by large pumps into the Sacramento River.

Measuring Zooplankton

To test how this export of floodplain-derived fish food might impact salmon growth in the river scientists placed floating cages containing juvenile salmon in the river at several locations. The fish were placed upstream of the pumping facility, at the outflow where pumps discharged into the river, a half-mile downstream, and one full mile downstream of the pumps. The site upstream of the pumping facility served as a control because fish growth at this site would be indicative of growth in the river without the addition of zooplankton-rich water from the flooded field. Thus, the results at the upstream site could be compared to those at the other sites to study the effect of adding the floodplain derived, food-rich water to the river.

Each week during the study, researchers measured the amount and types of zooplankton at each site and measured the fish from each enclosure for length and weight.

A Bug Buffet

As expected, the zooplankton counts in the flooded fields increased throughout the study. And not surprising, was the high percentage of Cladocera, food favored by the salmon, observed in the floodplain water. Over the time of the study, the amount of zooplankton documented in the river at the pumping station outfall increased about 40-fold while the site one mile downstream saw a six-fold increase compared to the upstream site.

By the end of the study, fish at the pumping entry site were two to three times longer and weighed four to five times more than the upstream fish. Similarly, fish at the downstream sites were two to three times longer and two to three times heavier. These spectacular results indicate that supplementing the river food web with zooplankton-rich water from intentionally inundated farmland during winter when crops are not grown can significantly increase the growth rate of juvenile salmon stuck in the food-scarce river.

A New Way Forward

But why is size important to a fish? Because one of the primary factors that influences whether a juvenile salmon will successfully return from the ocean is its size and weight at the time it enters the ocean. Thus, either of the two pioneering methods of getting juvenile salmon more to eat: getting the fish onto floodplain food factories or delivering the floodplain food to the fish in the river, should result in healthier, larger fish entering the ocean and an improved rate of return of spawning salmon to their natal rivers.

A New Era of Cooperation

Critically, this work has been done in an atmosphere of collaboration between all parties involved. Farmers, water districts, government regulators, scientists, and conservationists are working together to move beyond the old Water Wars narrative and, through science, chart a better future for the Central Valley’s fish, farms, and people.