Fish on Rice

A Modern Approach to Managed Landscapes for the 21st Century

By Jacob Katz, Ph.D., CalTrout Senior Scientist

My hands came up out of the muddy water and there it was, sleek and fat with silver sides flashing in the winter sun. What a surprise to pull such a beautiful little salmon from the turbid waters of a rice field. Salmon were supposed be in the river, not out here in the shallow, wetland-like waters of a farmed floodplain. But there it was: young, fat and healthy.

I had been taught (and had taken it as gospel) that salmon belonged in the river and that the river belonged in its banks. This little “floodplain fatty” was telling me that neither of those assumptions were necessarily so. This salmon definitely knew something we didn’t.

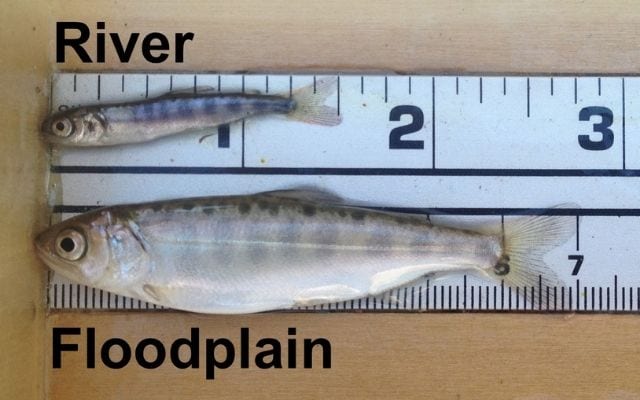

The Sacramento River was just a ½ mile from where I stood. In the cool, swift water between its steep leveed banks, tens of millions of small salmon were headed downstream to the ocean. I knew from experience those fish didn’t tend to look anything like the healthy, floodplain-fattened fish that I held in my hand. The fish stuck within the food-starved river channel were anemic, small and exceedingly unlikely to survive their journey to the sea and back. The fish I held was a glimpse of what a healthy Sacramento River salmon should look like. Similarly, the farm wetland that it was reared in was an indication that the Central Valley landscape could be managed to once again produce abundant salmon.

So was born the Nigiri Project in 2011. The project marked CalTrout’s first foray into the Central Valley, but in the ten years since those humble beginnings in a mud puddle in the corner of a rice field, the project has grown to be an indicator of the impact we can make at a major landscape-level scale. What we have learned in the floodplain mud has reshaped not only CalTrout, but also California’s efforts to manage our precious water resources. In just one short decade, the Nigiri Project has helped spawn a new vision for how to restore a functioning Central Valley river ecosystem, capable of supporting human communities and economies, as well as abundant fish and wildlife populations.

Nigiri Project fish pens on flooded farm fields. photo credit: Carson Jeffries

The Nigiri Project, named after a form of sushi with a slice of fish atop a compact wedge of rice, is a collaborative effort between farmers and researchers aimed at restoring salmon populations by reintroducing young salmon onto winter-flooded rice fields. These “surrogate wetlands” mimic the floodplain rearing habitat used historically by young salmon—a habitat that has been largely eliminated by human development of the Central Valley.

This public/private partnership has demonstrated that critical habitat for fish and birds can be recreated on farm fields during winter, when crop lands lay idle.

Historically, the whole Central Valley was a floodplain. In winter and spring, storm runoff and snowmelt would spill over riverbanks, creating vast biologically productive wetlands where aquatic life flourished. This incredible productivity supported a huge fishery in the Central Valley, where we once had one of the largest runs of Chinook in the world. Today, only 5% of Central Valley floodplains remain intact and three of the four native Chinook salmon runs are listed as threatened or endangered.

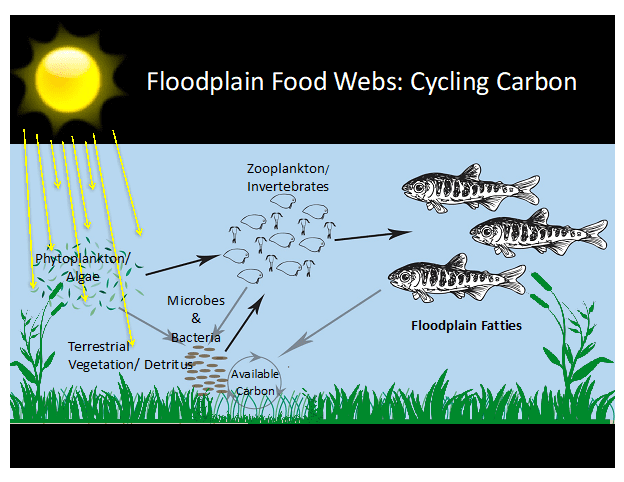

The Nigiri Project helped us to understand something simple, yet profound: sunlight makes sugar, sugar makes bugs, and bugs ultimately make fish. By seeing what a Sacramento salmon looks like when it's exposed to wetland rearing conditions similar to those to which it's adapted, we’ve come to understand how humans have fundamentally altered the underlying landscape of the Central Valley in ways that have severed the flow of energy through the landscape and into the river ecosystem.

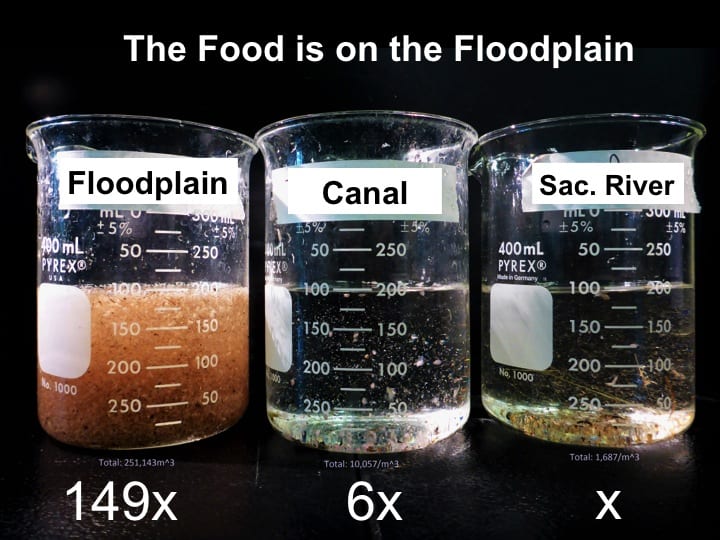

This is Not Rocket Science

But it certainly is physics. The known relationships between energy and mass (remember Einstein?) certainly apply. In the case of fish and floodplains, we can now see that the energy input into the river ecosystem comes, to a very great extent, from the act of spreading water out and slowing it down on floodplain wetlands. When water “puddles up” on the floodplain for a few weeks, it allows sufficient time for the aquatic food web to make abundant invertebrate fish food. As floods recede, the water (now rich in floodplain-derived food web resources) drains back into river channels bringing all those goodies with it.

Carbon—the foundation of an abundant, healthy Central Valley river food web—is created out on the floodplain, not in the river channel. Without actively inundated floodplains, that carbon doesn’t make it into the water nor into the aquatic food web.

In essence, levees are starving salmon and smelt populations.

We have lost 95% of our floodplains and wetlands, so why are we surprised that we have ended up with just 5% of our fish biomass?

The New Way Forward

Our work shows that endangered salmon and smelt populations are not an inevitable consequence of development.

The old ways separated species from the environment. Our new way integrates a 21st-century ecologic understanding of fish, wildlife and natural processes into the design and operation of California’s farms, rivers and water infrastructure, and incentivizes landowners to create solutions that work for both fish and farms.

Nigiri Project experimental fields on Knaggs Ranch

From Mud Puddle to Major Impact

A 5-acre experiment in the corner of a rice field on Knaggs Ranch showed that salmon and floodplain agriculture could co-exist. Today, CalTrout has expanded the program across the Central Valley, working with additional landowners to increase the scale and impact to a statewide level.

The Nigiri Project built lasting partnerships with agricultural landowners, water suppliers, bird conservation groups, local government, state and federal agencies where only acrimony had existed previously.

Scientific journal articles were published; articles were written in the state’s—and then the nation’s—major newspapers; local radio stories were picked up by National Public Radio; editorials placed in Sacramento, the Bay Area, and Los Angeles. Blogs large and small, including Smithsonian and the California Academy of Sciences, ricocheted around the Internet this story of farmers and environmentalists—odd bedfellows, indeed—working together in the very midst of California’s water wars.

The narrative of environmental hope and collaboration—central to our approach here at California Trout—ran counter to the frequently reported national story of conflict and litigation around the west’s natural resources, especially water.

The rigor of the science, the strength of the partnerships, the growing funding support from unexpected sources in government, water supply and agriculture all fueled the expansion of the scope, reach and ambition of our floodplain research throughout the Brown Administration. Small scientific studies led to proof-of-concept demonstrations at ever-increasing scale. The influence of the underlying concept, Reconciliation Ecology—that human landscapes must be managed to benefit wild species—began to be felt in ever-widening circles. This new approach reconciles fish, wildlife and natural processes into the design and operation of California water management, creating sustainable water solutions with global impact.

Here in California, we think of ourselves as the cutting edge of technology. After all, Silicon Valley is the global economic hub for the 21st century. But the resource that has the greatest effect on California’s economy isn’t silicon. It’s water. And the technology that ensures California’s water security and protects us from increasingly severe storms is woefully out of date, built to meet the needs of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Nigiri has shown that by integrating a modern scientific understanding of how river systems function into the management and operation of California’s outdated water and flood infrastructure, we can improve the resilience of both the aquatic ecosystem, and of California’s agricultural and urban water supply in the face of extreme climatic patterns, leaving California better equipped to deal with both bigger floods and longer droughts.

After all, it's right there in the CalTrout tagline: Fish. Water. People.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.