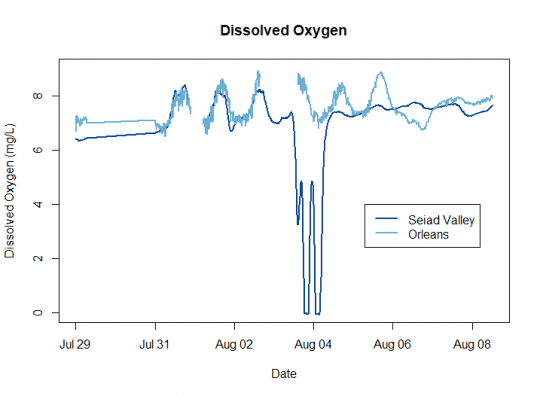

Debris landslides from the McKinney fire, triggered by thunderstorms and flash floods earlier this August, led to a prominent fish kill on the Klamath River, first reported by the Karuk Tribe. The debris flow into the river led to extremely low oxygen concentration (see graph below), plummeting to zero two nights in a row, according to data from a gauging station operated by the Karuk Tribe. (Watch a video of the intense flows.)

Data from the Karuk Tribe of the rapid Dissolved Oxygen (DO) drops from the debris flow events that occurred on August 3 to 4.

Dead fish were observed over 65 miles of the Klamath River from Humbug creek to Indian Creek. Tens of thousands of fish were found dead, but unfortunately, we are unable to get an exact estimation due to low visibility in the water from the slide and inability to access the location of the kill due to fire-fighting activities with damage assessments currently underway. Among the species observed were ESA-listed coho salmon (juvenile), Chinook salmon (juvenile), Klamath small-scale sucker, rainbow trout, Pacific lamprey, Klamath River lamprey, speckled dace, marbled sculpin, three-spined stickleback, Pacific giant salamander, and crayfish.

Photo by Stormy Staats, Karuk Fisheries

The Karuk Tribe has been working with Yurok Tribe, along with state and federal agencies, to gain access to the fire zone location to better document and evaluate the river conditions. These killed fish hold high cultural significance to the tribes, who have been powerfully fighting for years to protect fragile populations of salmon in the Klamath River. “When the river is doing poorly it hurts us too. It is an integral part of our culture,” said Karuk Tribe Spokesperson Alora Sutcliffe.

The fish kill appears to be over, and the river is slowly recovering. Water quality remains impaired throughout the Klamath system. It is unclear how this event will affect the fall migration of endangered Chinook salmon which has just begun. Salmon are already under a lot of stress in the Klamath watershed due to the presence of a series of dams which block over 400 mi of habitat and degrade water quality.

This event underscores 3 critical points:

1. The importance of holistic land management and prescribed burns for areas that require it. It’s time to work with nature, rather than against it. The Karuk people treated the Klamath mountains with fire to protect communities and manage resources for countless generations before the practice was outlawed. Prescribed fires allow for us to receive the benefits of natural fire regimes and lessens the intensity of impacts we receive from un-prescribed fires.

2. The need to take immediate action to restore Klamath fisheries. The removal of the 4 Klamath dams will improve water quality, restore natural flows, and give salmon access to hundreds of miles of high-quality historical spawning habitat. Dam removal should be complete by end of 2024. The dam removal plan includes the needed implementation measures to minimize impacts on downstream fisheries, and has considered all potential impacts including downstream Dissolved Oxygen (DO) levels. We are looking forward to the biggest salmon restoration project in history with the slated Klamath dam removal.

3. The significance of large-scale ecosystem management, from upland to the rivers and including all species of native fishes; viewing restoration to cover the entirety rather than segmented parts.

While we’re glad to hear that the adult salmon populations seemingly avoided the kill, the loss of any native fish is detrimental to both the ecosystem and those that rely on the fishery.

We’d like to thank the Karuk and Yurok tribes for their efforts documenting this unfortunate incident.

For up-to-date information on the McKinney Fire, see https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/8287/

Cover photo by Stormy Staats, Karuk Fisheries.