After more than a year, Sean Jansen, the writer and adventure junky completes his quest to retrace the 1,000 mile historic range of Southern California steelhead on foot. Find out his reflections below!

By Sean Jansen

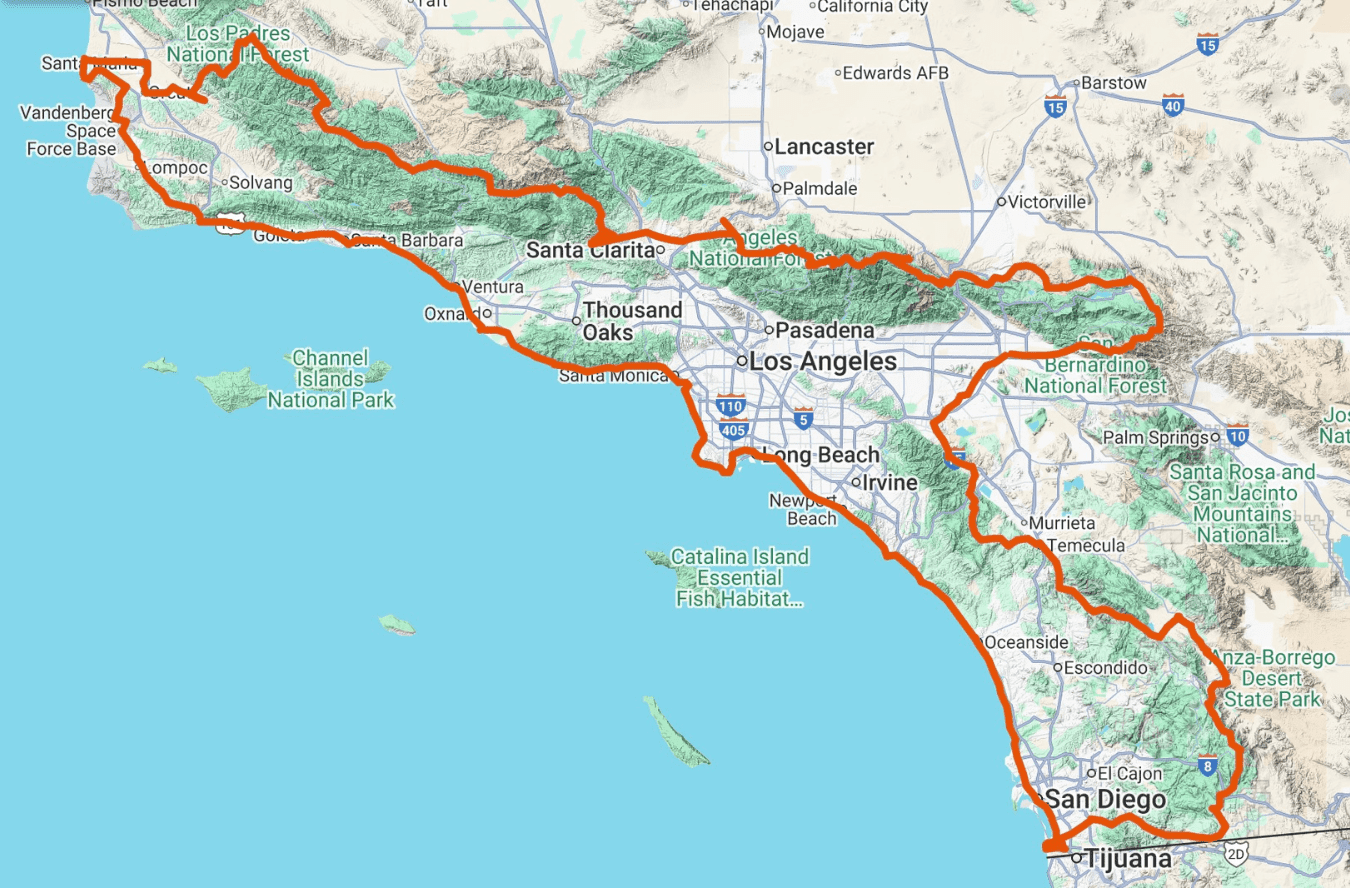

In April 2024, I started this trip in San Clemente with the goal of hiking along the entire historic range of Southern California steelhead to raise awareness of the struggles they face, teetering on the brink of extinction. I assumed it would be a 600-mile-loop. At the end of it all however, I assumed very wrong. I had walked up the coast to Santa Maria via the Pacific Coast Highway and by the time I got there, not only did I misjudge the time it would take to complete the trip, but also the distance.

After 300 miles and three weeks of hiking, I was only one third of the way done, and I hadn’t even started the mountainous section yet. But I tried not to think about it and once I made it into the mountains, was halted by some of the most heinous terrain I’d ever seen. Trails were gone, overgrowth swallowed the landscape, and dirt roads were being reclaimed by the forest. Feeling crunched for time, I hitchhiked around it and hit the Pacific Crest Trail, crushing miles to get to Big Bear. At this point, I wasn’t even halfway done with the trip but had to pause my journey to return to work.

My goal was to return in the fall to hit the section of the trip I had to hitchhike around, along with resuming where I had left off in Big Bear. I wanted to keep heading south but man-made fires ravaged the areas I needed to hike through and closures took over. My hands were tied and I had no choice but to wait until public access resumed.

By spring 2025, I was able to return to the area I had skipped around. However, the closures persisted and I still couldn’t make it south of Big Bear, having to wait once again until the fall to restart the trip. The next leg would include wrapping up the remaining southern section down to the U.S.-Mexican border, then finishing the loop around the historic range of the Southern steelhead.

By October 10, I had completed 700-miles after 54 days of hiking. I had walked from sea level to over 9,000 feet with terrain ranging from crashing waves to pine trees and snow. I followed in the footsteps of bears and heard mountain lion caterwauling. I also witnessed coastal sea birds dive bombing bait fish and listened to dolphins and even whales spout as they came up for breath. I thought I had seen it all until I restarted this final leg of the trip.

After hiking through a tropical storm that drenched the Southern California region in much needed moisture during its driest time of year, I was greeted by a 300-pound black bear that stumbled into camp on my first night. A few days later, I shivered in my tent at 11,502 feet atop the highest point in Southern California - Mount San Gorgonio - and looked below at the megalopolis that the inland cities of San Bernardino, Riverside, and Corona have become. Hiking down from that and back into the throes of concrete, I followed the Santa Ana River along a walking path rich with pollution, smog, and traffic, making me question the reason I chose to do this difficult trip in the first place.

Just when I became overwhelmed with doubts about the future of the trip (and the future of steelhead recovery), the top of a shoulder-less highway walk brought me to a view of nothing but pristine landscapes and wild terrain once again.

One constant throughout the trip was the extremism of the geography across landscapes, along with the demographic differences. In one day, I went from the highest point at eleven thousand feet and shivered at the arctic-like winds that beat at my tent throughout the night, all to wake up that morning, hike down to populated cities, and share that same day with thousands of people, traffic, and delicious Mexican food.

I would go from hiking in the most remote areas I have ever seen - the longest being eight days without even seeing a human - to walking in and around millions of people and going over and under major highways. The contrast within Southern California was a takeaway that astounded me. And the resiliency of the steelhead kept me, at least metaphorically, swimming with them through it all.

The contrasts continued throughout my journey. I hiked through wild and scenic river trails, mountain vistas, along highway roads, and even had near-death encounters with semi-trucks around blind curves. I would walk through creeks cascading over boulders and grunt my way through difficult sections in the sun along a bumpy trail or dirt road carrying seven liters of water for an intense dry section. My thoughts continuously returned to the steelhead, wondering how they survive. After nearly a month since restarting the trip, I had made it to the Mexican border, turned west and headed to the coast where I met the southernmost river in the historic range, the Tijuana River.

I prepared myself for the worst and was ready to see turbid water filled with trash and potentially dead animal carcasses. However, I was greeted with crystal clear water flowing into the sea and ocean waves. It was the most beautiful last chapter of the trip before the concluding section.

The conclusion was one of intense confusion. I felt no real sense of accomplishment, no real sense of pride. Because of the extended nature of the trip and the closures I had to navigate, it didn’t feel like a near three-month journey. But on my last day coming into my hometown of San Clemente, I walked along the bike path at Camp Pendleton enroute to my hometown water of San Mateo Creek with visions of clear skies, fresh swell at my local surf break, and a group of people all waiting to cheer me to the finish. Instead, I was greeted by something else.

Fog encapsulated the coast and wrapped its cold, grey blanket around all in its sight. But with each step I took, the fog cleared. It was as if I had a shield on that penetrated the grey and lifted its curtain - allowing the gorgeous and warm sunshine to come down to earth. When I reached the banks of San Mateo Creek, the grey lingered. I thought it was the perfect metaphor. I was allowed to complete the trip and circumnavigate its historic range – finishing exactly where I left off in my hometown of San Clemente - but just because the trip was complete, never meant the creeks or the fish were in the clear. Work still needed to be done.

One thing I reflected on as I lay in my bed that night at home, while cuddling my stuffed animal steelhead I used as a pillow on the trip, was that with each of the river systems I encountered within the range, their headwaters were pristine - untouched. Only a small handful of them flowed freely to the sea. The rest were dammed, diverted, polluted, blocked, or dried up.

So, in my unscientific eye the solution is simple: create pathways for these fish to get to the headwaters. If they can do that, the pristine nature of the headwaters will let them flourish and repopulate areas they once did. CalTrout and their partners are hard at work on exactly that: removing barriers to allow the fish access to these headwaters once more, and, after this trip, I couldn’t support this approach more. The remarkable nature of these fish astounded me and inspired me to never lose hope. If we give them a drop of water, they’ll use that and swim as far as they can, we just have to let them. And with the recent CESA protections given by state of California, hope is on the horizon.

By some estimates, nearly 60 percent of California’s population lives in the lower third of the state, yet so few of them seem to know these fish even exist. The goal of my journey has always been to spread awareness about Southern steelhead as far and wide as I can – and I’m hoping that writing a book will help me achieve this goal. The more people that learn about steelhead - their incredible perseverance and treacherous plight – the more people that will become advocates on their behalf. We can all help protect Southern California’s special fish and biodiverse ecosystems – and this all starts with awareness. At the beginning of my journey I believed Southern California was overpopulated and polluted, far from an intact and wild ecosystem where native species could live, let alone thrive and a place that I thought would be an easy and relaxing project to backpack – I have never been so wrong, and I have never been so happy and humbled to accept that.

Southern Steelhead Historic Range Circumnavigation by the Numbers:

Walked 1,196.39 miles, totaled 86 days to complete, took 2,610,706 steps, burned 165,745 calories, crossed 478 cross walks, crossed 26 railroad crossings, took 29 showers, encountered 4 days of rain, 2 days of snow, passed by 13 Ferraris, walked 12 piers, hitchhiked 10 times, rattled at by 10 rattlesnakes, witnessed 1 potential steelhead, and had 1 helluva trip!