Foreword By Ted Grantham

Professor of Cooperative Extension, UC Berkeley, PPIC-CalTrout Ecosystem Fellow (2019-2020)

"California has more than 1,400 large dams and tens of thousands of smaller impoundments on its rivers and streams. These dams have created barriers to fish movement, altered natural seasonal flow patterns in rivers, and are a primary cause of native fish population declines in the state. While dams will continue to play an essential role in managing water in California, many aging dams have outlived their functional lifespan. These include dams with sediment-filled reservoirs, those with non-functional hydropower facilities, and those at risk of failure, threatening downstream communities and ecosystems. The removal of such dams has the potential to bring substantial environmental benefits, while also supporting the economic and recreational activities associated with free-flowing rivers. However, the removal of dams is time consuming, expensive, and can be politically charged. That is why a science-based approach for prioritizing dams for removal is critical.

In the 2022 Top 5 Dams Out report, CalTrout has identified 5 dams that are ripe for removal. The selection of these dams was informed by the review of past scientific studies, understanding of their impact on salmon and steelhead, awareness of their regulatory context, and sustained engagement with the communities in which of the dams are located. By strategically pursuing opportunities for dam removal where economic, social, and environmental interests strongly align, CalTrout offers a model for restoring the health of the state’s rivers for the benefit of fish and people."

Cover Photo: Kyle Schwartz

Why Dams Out?

California Trout is advocating for the removal of obsolete dams in order to forward our mission of ensuring healthy watersheds and resilient wild fish for a better California.

Dams can disrupt watershed health, harm fish populations, create public safety concerns, and degrade surrounding ecosystems which hold cultural importance for many.

Photo: Mike Wier

Watershed Health

Dams alter the timing of river flows, trap sediment, remove water below dams, and increase water temperature which can result in algal blooms.

Photo: Thomas O'Keefe

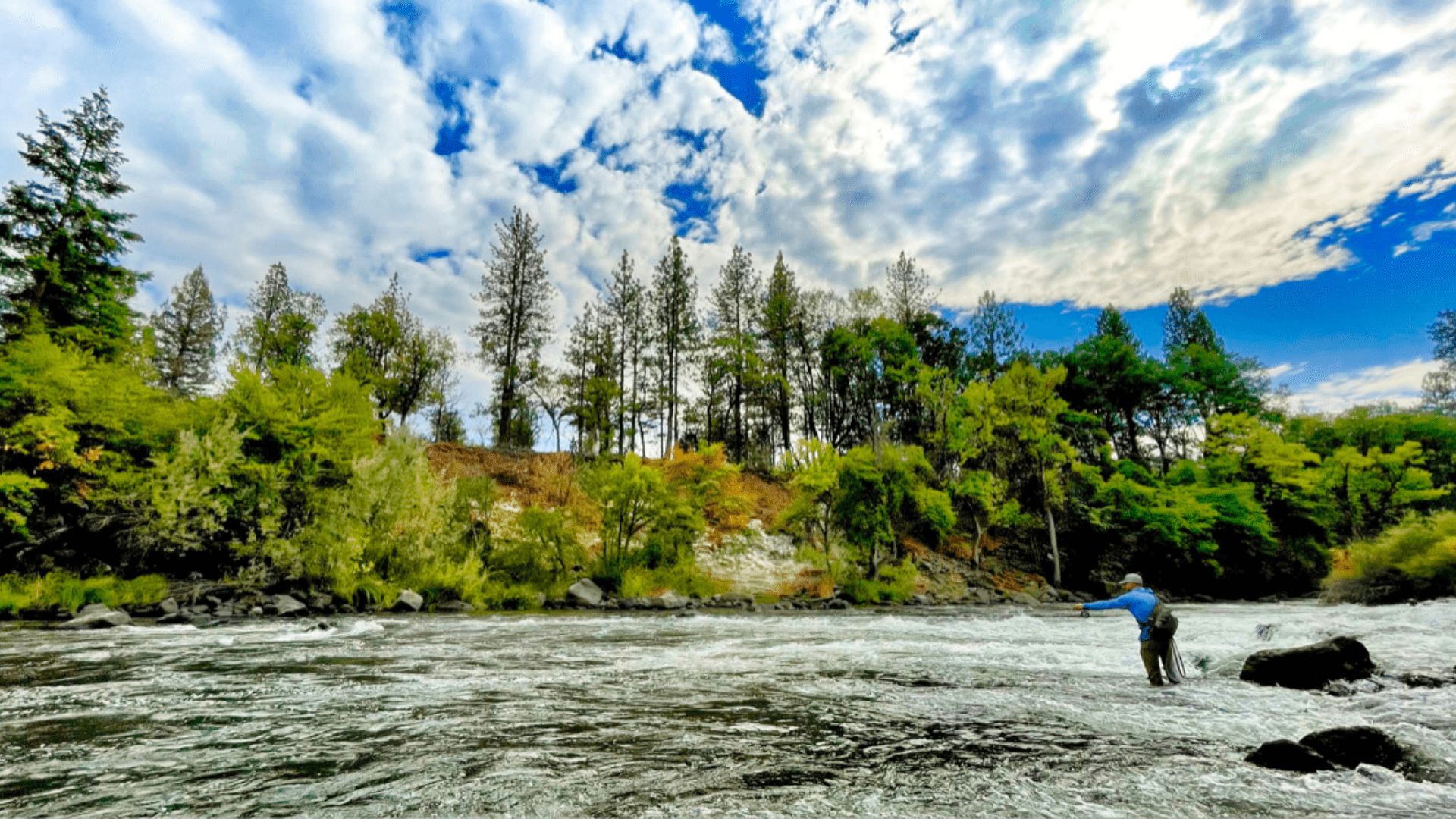

Fish Populations

Dams prevent fish migration, alter habitat, limit spawning habitat access, and are a primary cause of native fish population declines in California.

Photo: Joe Cavaretta

Public Safety

Since 1850, there have been 1,645 dam failures in the United States. Combined, those failures have resulted in 3,495 lives lost.

Photo: Thomas O'Keefe

Cultural Importance

Many people — including Native Americans — have strong connections to water and the surrounding land. Dams harm both the water and land, disrupting these relationships.

Photo: Thomas O'Keefe

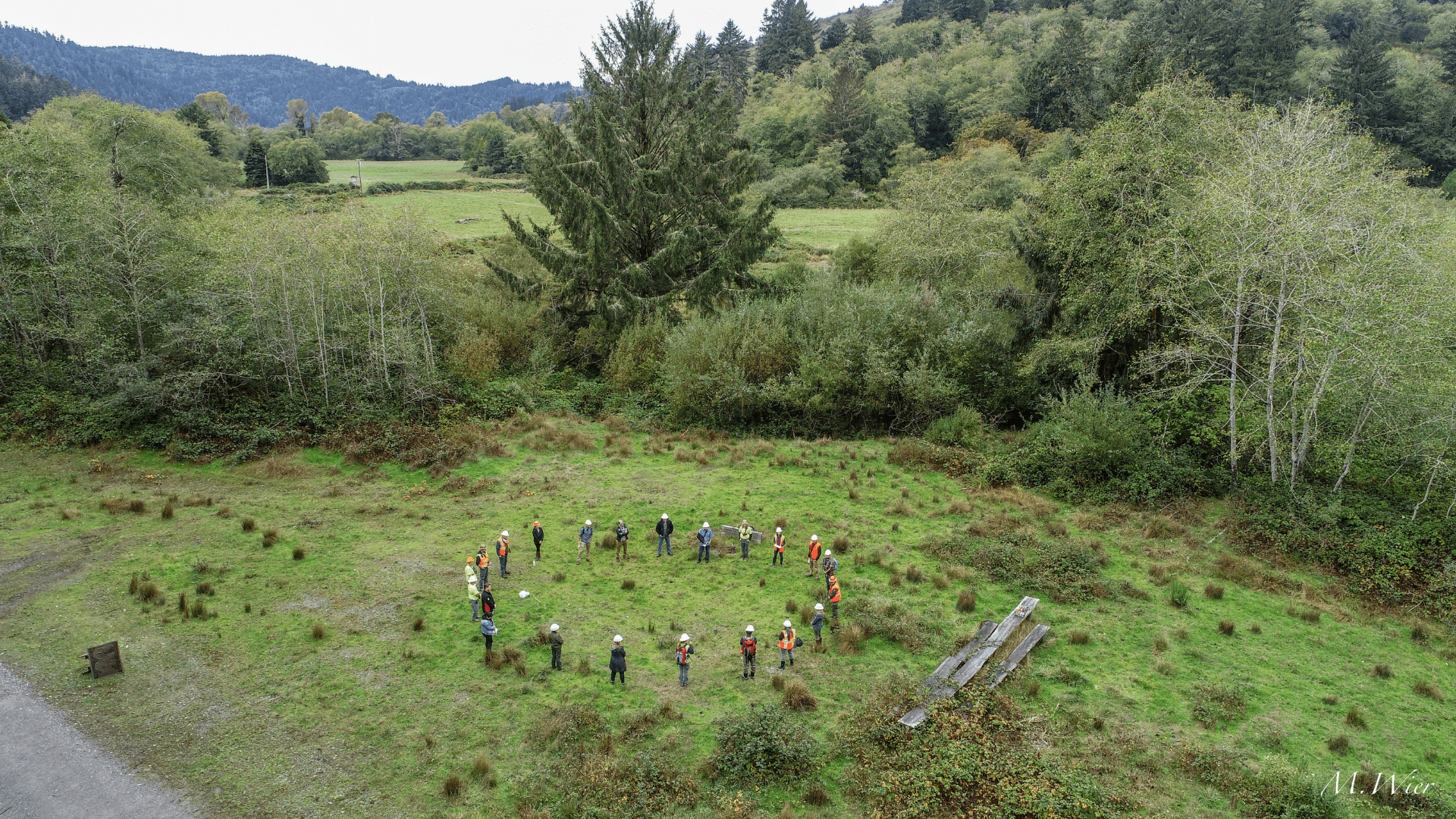

A New Era of Dams

The 1930s to the 1960s was an era of large-scale hydroelectric dam building across the United States.

The construction of these dams was important for electricity production and flood control, but today, many have outlived their useful lifespans. We have now entered a new era in which we must reevaluate the utility of aging infrastructure — and take down those dams that are no longer useful or safe.

Dam removal is far from unprecedented. Between 1912 and 2020, 1797 dams were removed nationwide. In 2011, the giant Ellwha River dams in Washington State came down. In 2015, the 106-foot-tall San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River was removed. Soon, the Klamath Dams are slated to follow. The removal of these dams, and others that have aged beyond usefulness, can have tremendous benefits for fish populations and watershed health.

Photo: Mike Wier

U.S. Dams Removed Since 1912

Each orange dot on this map represents a dam that has been removed between 1912 and 2020. To learn more about a removed dam, click on a dot on the map.

Map Source: American Rivers . 2021.

Water supply and storage in California are crucial today in the face of extreme drought and widespread wildfires. However, maintaining a large number of dams and their subsequent reservoirs is not always the best option.

In some California watersheds, when large dams were built following the construction of smaller dams, this created a redundancy: more storage space than water exists in these watersheds. In this situation, more water is lost to evaporation from the reservoir surfaces than would be lost if the water storage were concentrated to fewer reservoirs. This means that, for some watersheds, the most effective way to supply and store water is to decommission some of those dams.

Instead of focusing solely on dam reservoirs, there are many other options for water storage . Recycling water, including treated sewage, graywater, or stormwater can help meet non-potable needs such as irrigation and fire protection. Groundwater recharge is another water supply solution.

Many dams in California do provide benefits to Californians including flood control, water supply, and hydroelectric power. However, the dams included in this report have been carefully selected as dams that have outlived their functional lifespans.

The cost of leaving these dams in place far outweighs the ecosystem and economic benefits of removal. Read on to learn about California Trout's Top 5 Dams Out.

California Trout's Top 5 Dams Out:

Klamath Dams

Scott Dam

Matilija Dam

Rindge Dam

Battle Creek Dams

Interact with the map by clicking on a black dot, representing a dam, and then click "Zoom to".

Klamath Dams

Removal of the dams has been the subject of national attention for nearly two decades.

Photo Credit: Mike Wier

The Problem

Copco #1, Copco #2, Iron Gate and J.C. Boyle (in Oregon) are four aging hydroelectric dams on the mainstem Klamath River, which flows through parts of Southern Oregon and Northern California.

Over 40 organizations, irrigation districts, and many Native American Tribes support taking the dams out. Tribal leadership has been a central component of the dam removal effort. The Yurok, Karuk and Klamath River Tribes have led the effort to restore part of their cultural heritage and subsistence fishing for salmon and lamprey.

The Klamath dams block salmon and steelhead from reaching more than 300 miles of spawning and rearing habitat in the upper basin. Historically, the Upper Klamath-Trinity Rivers spring-run Chinook salmon was the most abundant run on the river. Today less than 3% remain, in large part because they cannot access historical habitat in the Upper Klamath Basin.

Current Situation

A non-profit organization, the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), was formed in 2016 to take ownership of four PacifiCorp-owned dams (Copco #1, Copco #2, Iron Gate and JC Boyle), for the purpose of overseeing the dam removal process. That work will include restoring formerly inundated lands and implementing required mitigation measures in compliance with all applicable federal, state, and local regulations. PacifiCorp will continue to operate the dams until FERC approves a license transfer to KRRC. The transfer of the FERC license from PacifiCorp to KRRC is currently pending before FERC and is expected to be completed by summer of 2022.

All the pieces are in place for these dams to be removed by 2023 pending the license transfer. Removing the Klamath dams will be the largest dam removal project in in the United States, restoring river health and fish abundance and providing social justice to tribal people who have relied on salmon for subsistence for thousands of years.

Photo Credit Left: Mike Wier; Right: Dominic Bruno

Scott Dam

The Eel River represents perhaps the greatest opportunity in California to restore an entire watershed and abundant populations of wild salmon and steelhead.

Photo Credit: Kyle Schwartz

The Problem

Scott Dam is one of two dams that make up the Potter Valley Hydropower Project. The Project, owned by PG&E, consists of Scott and Cape Horn dams, two reservoirs, a diversion tunnel that sends water south to the Russian River watershed, and a powerhouse. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) license for the Project expires on April 14, 2022, and will not be renewed. PG&E will thus likely be directed by FERC to prepare a Surrender and Decommissioning Plan for the Project.

Fish populations in the Eel River are severely depressed. Although the Eel River once boasted some of the best salmon runs in California, the river’s salmon and steelhead populations are all listed as threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act. Scott Dam is the largest barrier to native salmonid habitat in the Eel watershed and throughout the entire north coast. Water quality throughout the Eel River is listed as impaired under the Clean Water Act for excessive sedimentation and high temperatures.

Current Situation

The Eel River represents perhaps the greatest opportunity in California to restore an entire watershed and abundant populations of wild salmon and steelhead.

With PG&E’s decision to withdraw from relicensing the project, CalTrout and others recognize a unique opportunity to steer the future of the Eel River toward robust fisheries and a healthy watershed. We also recognize the opportunity to reverse the long-lasting impacts to Native American Tribes from a century and a half of habitat degradation and overharvesting impacts.

In 2019, CalTrout teamed up with Round Valley Indian Tribes, Sonoma Water Agency, Humboldt County, and Mendocino County Inland Water and Power Commission to file a Notice of Intent to take over the project and implement a Two-Basin Solution. Unfortunately, the $18 million of funding needed was not able to be raised, in large part because PG&E was unwilling to help. At a crossroads, in January of 2022, the coalition informed FERC it would no longer be submitting a Final License Application by April of 2022 and were effectively withdrawing their Notice of Intent to take over the Potter Valley Project. FERC is now expected to initiate a License Surrender process with PG&E that will lay out a project decommissioning plan.

Now, CalTrout is pivoting to work on the License Surrender process. Our Two-Basin Partership received a $1 million grant from the Department of Fish and Wildlife to assess the feasibility of removing Scott Dam and Cape Horn Dam. We enter this next phase more informed about this complicated project. We remain committed to working with Congressman Huffman and other stakeholders in this process so that we can return fish to the upper Eel River basin.

Photo Credit Left: Jim Inman; Will Boucher; Right: Dominic Bruno

Matilija Dam

For almost 20 years a broad coalition of community groups and resource agencies have been advocating for dam removal and working together to develop a comprehensive strategy to restore the Ventura River.

Photo Credit: Mike Wier

The Problem

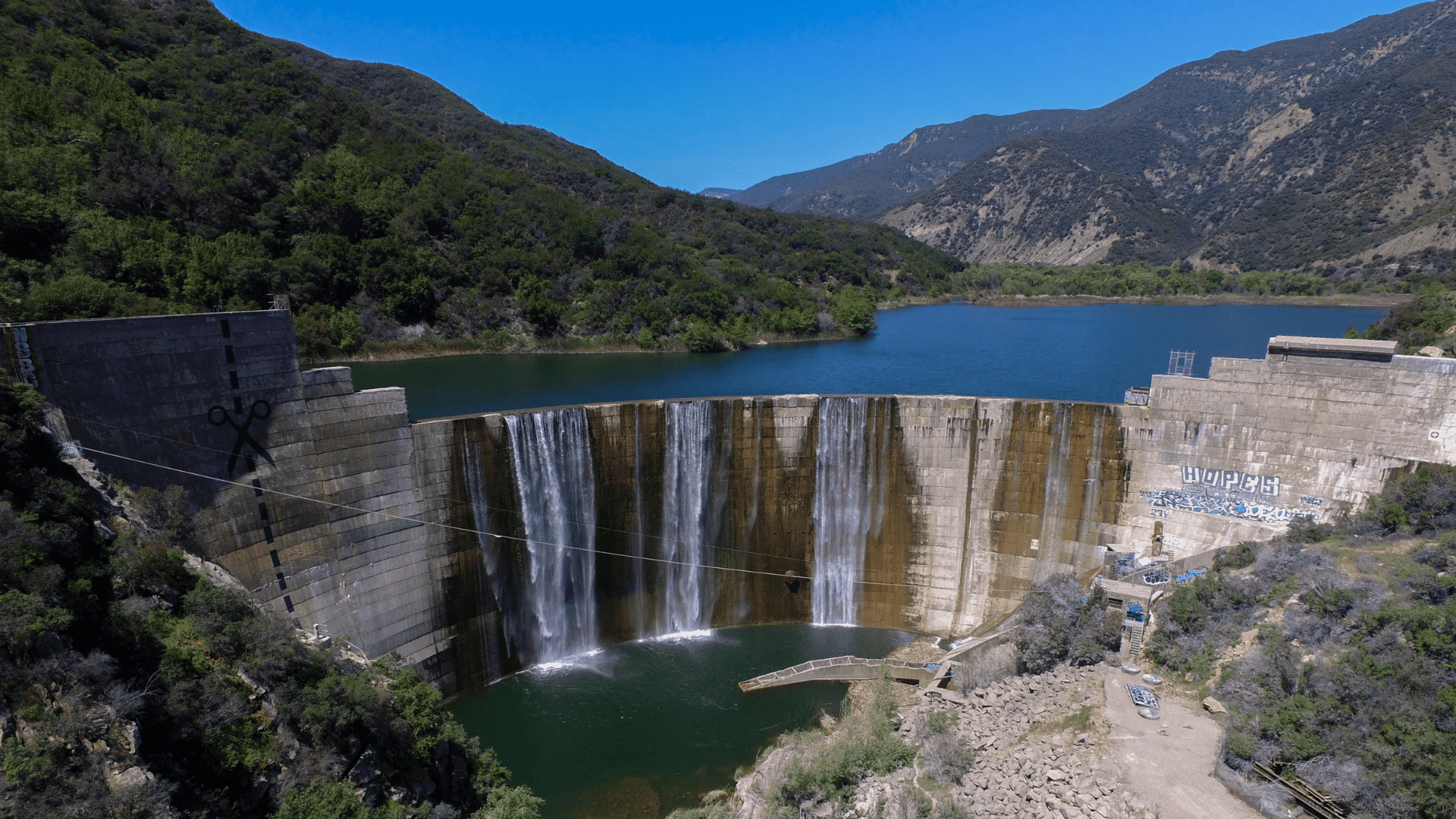

Matilija Dam, located in the Ventura River watershed on Matilija Creek north of Ojai, is a concrete arch dam built in 1947. Infamous for the scissors painted on the dam by graffiti artists in 2011 that have become an iconic symbol for dam removal, it was originally designed for water storage and flood control.

The reservoir behind Matilija Dam is nearly completely clogged with sediment, significantly reducing storage capacity to the point of rendering the dam non-functional. With no fish ladder or bypass structure present, it is a complete barrier to the migration of endangered Southern California steelhead.

Southern California steelhead are an incredibly important species because they evolved in seasonally disconnected systems and can survive in warmer waters than other steelhead populations. With only an estimated 500 individuals remaining, this life history trait makes them a particularly valuable population to protect in the face of climate change. The removal of Matilija Dam will restore access to 17 miles of spawning, rearing and foraging habitat above the dam.

Current Situation

For almost 20 years a broad coalition of community groups and resource agencies have been advocating for dam removal and working together to develop a comprehensive strategy to restore the Ventura River. Ventura County officially made the decision in 1998 to remove the dam altogether. Congressional approval for a preferred preliminary design was obtained through the Water Resources Development Act of 2007, but was not funded.

The Matilija Dam Ecosystem Restoration Project will cost millions of dollars and the lack of dedicated funding has been a major impediment to action. Regardless, all stakeholders agree, Matilija Dam must come down.

In 2016, the group overseeing design alternatives voted in favor of a removal plan. The approved alternative will use two bore holes at the base of the dam to remove and transport the impounded sediment. Current projections estimate that once the bore holes are opened, complete dam removal and a free-flowing river will be achieved in 2 to 5 years.

In 2021, we saw immense progress. With funds from California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), construction began to replace Santa Ana Bridge, a downstream structure that must be modernized before the river can be set free since the current bridge’s span is undersized. This pre dam removal work is moving forward and on-schedule for completion in 2022. Ventura County also is in the process of finalize funding awards with the State Coastal Conservancy and the Wildlife Conservation Board to fully fund final designs to update Camino Cielo.

Photo Credit Left: Mark Capelli; Right: Bernard Yin

Rindge Dam

The removal of Rindge Dam represents a unique opportunity for systemic and sustainable ecosystem restoration in highly urbanized Southern California.

Photo Credit: Mike Wier

The Problem

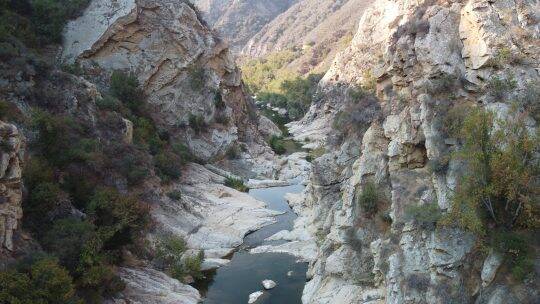

The 100-foot-tall Rindge Dam in Malibu Creek is located in the Santa Monica Mountains, about three miles upstream from Southern California’s Malibu coastline. Construction of the concrete dam and spillway structure was completed in 1926 on the Rindge family property and provided water for irrigation and household use in Malibu. The reservoir filled entirely with sediment by the 1940s, and the dam was decommissioned in 1967. It was purchased shortly thereafter by California State Parks and is now part of Malibu Creek State Park.

Rindge Dam has altered the natural geomorphic, riparian and aesthetic character of Malibu Creek. The dam has trapped over 780,000 cubic yards of sediment that was naturally destined for the coastline, where it would support beach nourishment and reduce coastal erosion.

The lower three miles of Malibu Creek below Rindge Dam is designated critical habitat for the federally endangered Southern California steelhead. The dam is a barrier to Southern California steelhead and blocks their access to high-quality spawning and rearing habitat. Moreover, Rindge Dam prevents steelhead from accessing more than 18 miles of historic spawning and rearing habitat in Malibu Creek and tributaries.

Current Situation

The removal of Rindge Dam represents a unique opportunity for systemic and sustainable ecosystem restoration in highly urbanized Southern California. Rindge Dam was deemed obsolete due its lack of function as a water storage facility and has been the subject of removal planning for decades.

The Locally Preferred Plan (LPP) was selected as the preferred alternative for dam removal. The LPP calls for the removal of the concrete arch dam and spillway; removal or modification of eight smaller upstream fish passage barriers; and removal of ~780,000 cubic yards of impounded sediment.

The Malibu Creek Ecosystem Restoration Study Final Integrated Feasibility Report was completed in November 2020 and signed by Commanding General Scott Spellmon in December 2020. The design phase of the project will begin in 2022. Over the next four years, CDPR will lead the design phase of this project, which will include additional technical studies; dam removal design in sequential phases to a 90% level of completion; environmental permitting; and public outreach and education.

Photo Credit Left: Bernard Yin; Right: Bernard Yin

Battle Creek Dams

Historically, Battle Creek was home to a diverse assemblage of anadromous and resident fishes adapted to its specific hydrology and habitats. Today, eight dams block fish access.

Photo Credit: Damon Goodman

The Problem

The Battle Creek Hydroelectric Project was originally developed to support the power demand of mineral extraction in Shasta County including Iron Mountain Mine near Redding. The Project included 8 low-head dams within anadromous reaches, an additional 4 dams outside of the anadromous habitat, and a complex network of 20 diversion canals and pipelines.

Historically, Battle Creek was home to a diverse assemblage of anadromous and resident fishes adapted to its specific hydrology and habitats. North Fork Battle Creek is spring-fed with water originating from the flanks of Mt. Lassen and provided ideal spawning, holding and rearing habitats for winter-run Chinook Salmon. This run or ecotype is unique to California and is one of the most endangered salmon.

The South Fork Battle Creek hydrograph is storm driven and has deep holding pools that provide habitats for spring-run Chinook Salmon which are listed as threatened on the Endangered Species Act. Anadromous steelhead trout, Pacific Lamprey and a host of native resident fish species reside in the drainage. The construction of the Battle Creek Project virtually eliminated access to 42 miles of anadromous habitat as well as connectivity for resident fish populations.

Current Situation

There is new hope on the horizon to provide volitional passage to all historical fish habitats in Battle Creek and restore it’s natural hydrograph. PG&E was in the process of renewing a federal (FERC) hydropower license before its expiration on July 31st, 2026. Over 2 decades of planning and restoration efforts were underway to balance the needs of native fishes with hydropower generation. In 2020, PG&E filed notice of its intent to not file an application for a new license and no other party filed a notice of intent to assume responsibility of the project, which will likely lead to decommissioning. Restoration efforts have now pivoted to preparing for project decommissioning and maximizing the benefit for native fishes.

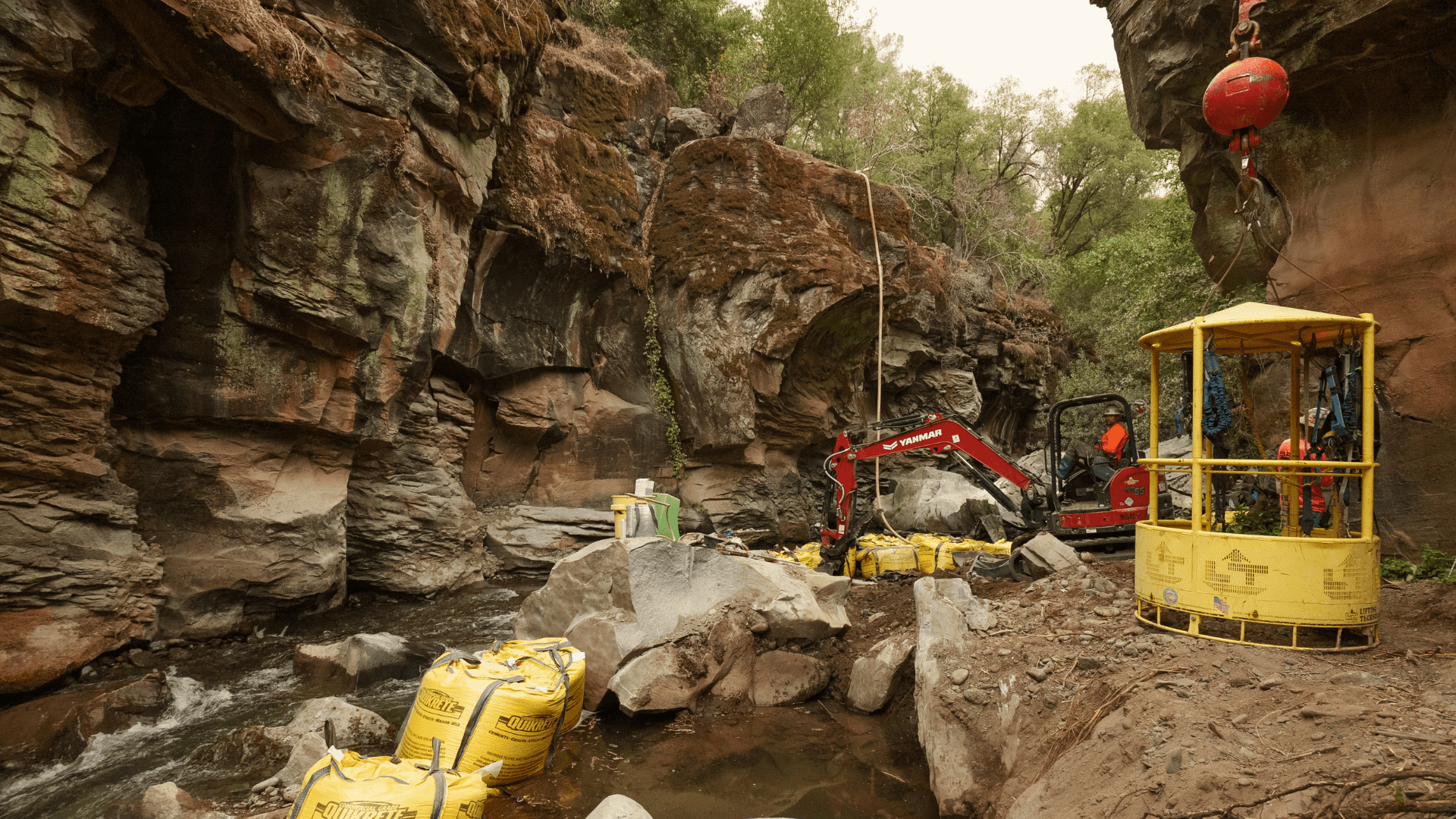

CalTrout is a member of a team that is leading the way to restore Battle Creek. In 2021, CalTrout and others completed a project on NF Battle Creek to restore access to 4 mi of winter-run Chinook Salmon habitat. This project created a foundation for future progress in Battle Creek and other rivers in California. Read more about this project.

Removal of several dams are already underway through the Battle Creek Salmon and Steelhead Restoration Project. The first dam removal occurred in 2010 with the removal in Wildcat Dam on the North Fork which opened miles of anadromous fish habitat. Efforts are now in progress to initiate the removal all dams in the South Fork as well as provide passage beyond the remaining North Fork Dams.

Photo Credit Left: Damon Goodman; Right: Pusher Studios

A new era of dam removal is ongoing. Looking to the success of other dam removals, CalTrout is excited for a future in which these five dams no longer disrupt watersheds and when rivers are free flowing once more.

To learn more about our top 5 dams, check out our Dams Out StoryMap.

To view our full Dams Out campaign, stay tuned for the release of our Top 5 California DAMS OUT Report. Support dam removal in California by donating to CalTrout's Reconnect Habitat Initiative today.

Photo Credit: Michael Marois