Watch CalTrout's video on our project at Eagle Canyon on Battle Creek.

Reconnecting Winter-run Chinook Salmon with their Historical Source Waters

Eagle Canyon Passage Project, Battle Creek, CA

By Damon Goodman, CalTrout Director of Mount Shasta-Klamath Region

When you think about California’s grandeur, it’s hard to pin it down...

It’s not just big mountains, or the hottest deserts, or the tallest trees, or the clearest lakes and most beautiful beaches. Unlike many states that have one or two iconic features, our state has too many to list, from the geological to the biological and everything in between. During a recent retreat to San Diego, I spent each sunset looking past the waves in search of the Green Flash, hoping for a glimpse of a fluorescent green sky. Somehow it always seems to evade me, but I keep looking anyway.

I can’t help but add the majestic sequoia forests to the list—the largest trees known on our planet, with General Sherman standing 275 ft tall with a diameter of 37 ft. Likewise, the north state volcanoes, Mt Shasta and Mt Lassen, dominate the viewscape of the I-5 corridor and help to shape the hydrology and culture of Northern California. From a fisheries perspective, the list goes on and wouldn’t be complete without winter-run Chinook salmon, a distinct member of California’s biodiversity found only within the Sacramento Valley. And you wouldn’t know it by looking, but the real beauty of California is that these features are all connected, from the highest mountains to the smallest fish in the streams. Read on as we explore the unique biology of winter-run Chinook salmon and efforts that are underway by CalTrout and our partners to conserve them.

Cover photo: Pusher Studios

Let’s start by taking a trip back in time...

Let's envision the landscape that shaped the evolutionary trajectory of winter-run Chinook salmon. Try to imagine San Francisco Bay and the Sacramento River 200 years ago: The Bay, a complex of wetlands and tidal marshes creating aquatic habitats that fish biologists now only dream about; coastal redwood forests surrounding the Bay and its streams; the banks of the Sacramento River, lined by seasonal floodplains and wetlands providing low velocity habitats and conditions that drive the aquatic food web; upland forests and meadows, open and healthy from frequent fire, providing copious amounts of cool water to headwater streams. No man-made obstacles stood in the way of anadromous fishes as they swam their way to their birth places in headwater habitats on a mission to reproduce and start the cycle again. The upper extents of fish migrations were determined by waterfalls rather than dams. These habitat conditions led to the evolution of four different runs of Chinook salmon each named for the season that they return from the Pacific Ocean and cross under the Golden Gate Bridge. The life history diversity in the Sacramento River rivals any river in its distribution of species. Each run takes advantage of distinct ecological niches.

Background Photo: Val Atkinson

Winter-Run Chinook Salmon

Winter-run Chinook salmon evolved to take advantage of spring-fed source waters and seasonal runoff. Unlike other runs of Chinook salmon, winter-run migrate from the ocean during the winter. Using routes available during elevated river levels, these fish migrate high into source waters where they reproduce during the springtime. Young fish or fry then emerge from redds during the hottest summer months and rear into the fall. Due to the upper thermal tolerance of the species, this life history strategy is made possible by the cold spring water available during the warmest months when other rivers are flowing low and warm.

Background Photo: Mike Wier

The historical spawning habitats of winter-run are limited to the upper Sacramento River, McCloud River, Pit River, and Battle Creek. These rivers are well known for their spring waters bubbling up from basaltic aquifers created by historical eruptions of the iconic volcanoes Mt Shasta and Mt Lassen. Because these watersheds are lined with permeable rock, water is able to percolate from mountain flanks to rivers through a maze of lava tubes. The process takes decades and creates ideal habitat for this endemic California run of Chinook salmon.

Background Photo: Battle Creek, Pusher Studios

Fish Passage Obstructed

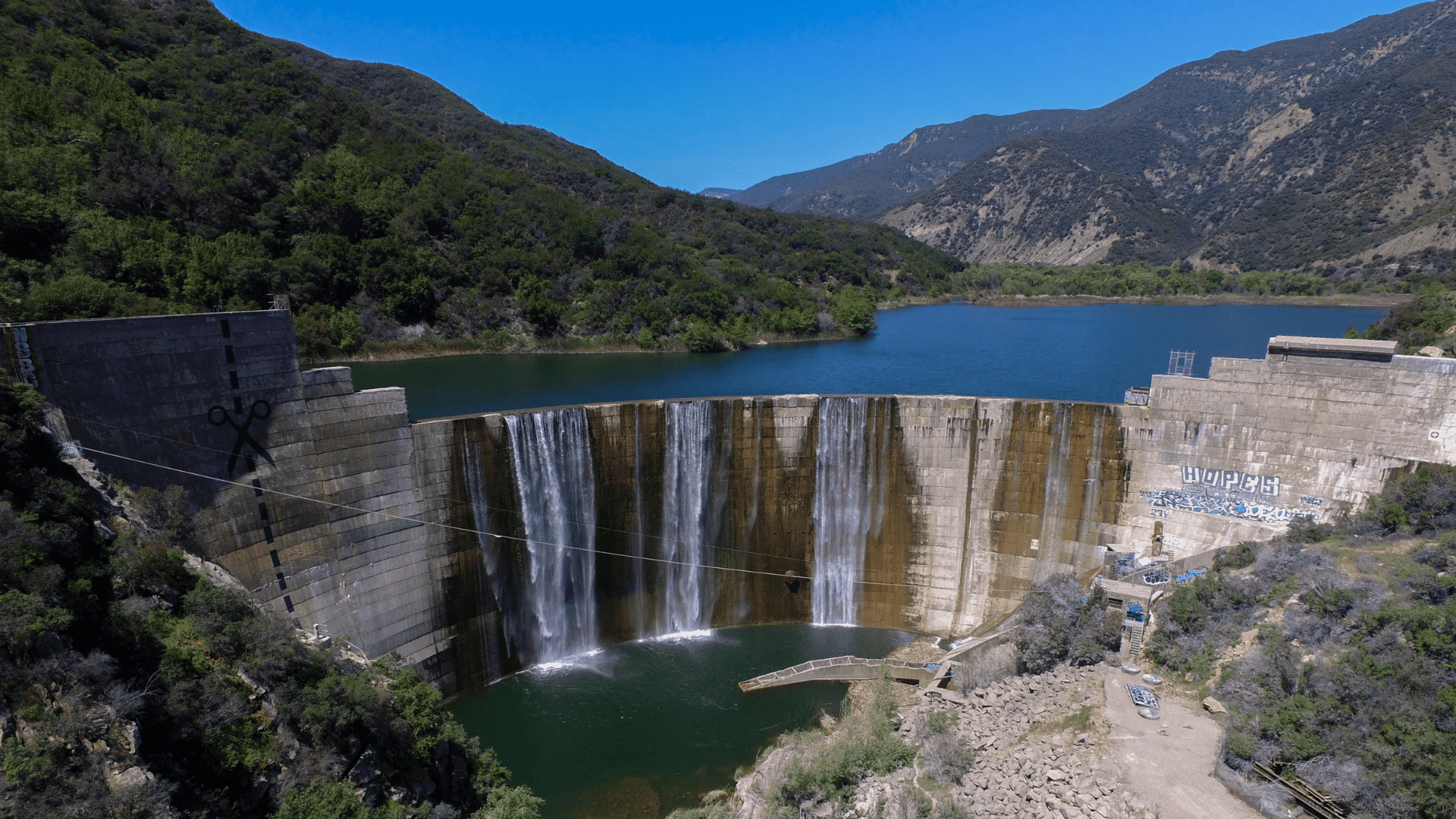

Unfortunately, the consistent year-round streamflow that supported the evolution of winter-run also led to its exploitation through the development of dams and hydropower that lack fish passage facilities. The source waters that historically provided spawning habitat are now completely blocked behind impassible man-made barriers such as Keswick Dam and the Battle Creek Hydroelectric Project, and winter-run are on life support, listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act —the highest level of concern afforded by the law. Given winter-run are unable to access the places they evolved in, it’s no surprise that the species is heading toward extinction.

Winter-run are now just a small percent of their historical run size, crashing from over 100,000 fish per year now down to just hundreds. Their only extant population is in the Sacramento River, downstream of Shasta and Keswick dams, surviving on the unnatural thermal regime provided by management of the dam and supplementation from the Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery. However, drought is testing the capabilities of this life support system, bringing high temperatures and low reservoir levels. In 2021, California Department of Fish and Wildlife studies suggested that less than 3% of winter-run survived from hatch to downstream migration to the Bay and this estimate does not include mortality from the rest of their lifecycle.

CalTrout and our partners are stepping up to conserve winter-run through on-the-ground restoration projects such as the Eagle Canyon Fish Passage Project.

Background Photo: Pusher Studios

Eagle Canyon

In 2021, construction was completed on the rock barrier in Eagle Canyon, resolving the largest fish passage barrier in North Fork Battle Creek and reconnecting miles of anadromous habitat. This project was a huge step toward reconnecting winter-run Chinook salmon with their historical habitats. The success of the project depended upon close coordination and support from a host of government agencies, private landowners, construction firms and more. The project design process included data from water level monitoring, site mapping, LiDAR surveys, hydraulic modeling, and more to ensure the success of this hard-core restoration project.

Background Photo: Pusher Studios

To add even more complexity to the project, the construction site was located 275 ft below the canyon rim in a steep-walled gorge at the end of a dirt road. The implementation team used a 300-ton crane to move boulders the size of trucks and to configure the river to mimic the surrounding natural stream channel making the river passable to fishes of all life stages. The project resulted in the removal of 3.6 million lbs. of rock from the river channel—roughly the equivalent of the weight of the giant sequoia tree General Sherman.

Background Photo: Pusher Studios

Although the Eagle Canyon Project was a success, our work is far from over.

Background Photo: Pusher Studios

Future Opportunities on Battle Creek

CalTrout and our partners are stepping up to do what we can to help, and we are currently working toward another large-scale passage project to continue the momentum. In parallel, the Battle Creek Hydroelectric Project has seemingly outlived its utility. In 2020, Pacific Gas and Electric Company withdrew its application to relicense the project with the Federal Energy Commission and has now opened the door to decommissioning of the dams that make up this antiquated hydroelectric project. The federal license for the Battle Creek Hydroelectric Project is set to expire in 2026 and a new hope is on the horizon for restoration of Battle Creek and its native fish fauna.

Background Photo: Pusher Studios

Restoration of Battle Creek is arguably the best opportunity in the world to change the trajectory for winter-run, and though the Green Flash may continue to evade me, opportunities like this will not.

Background Photo: Pusher Studios

CalTrout Partners on Battle Creek

Battle Creek Watershed Conservancy, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, NOAA Fisheries, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, PG&E, California Bay-Delta Authority, California State Water Resources Control Board, FERC, The Nature Conservancy, California Wildlife Conservation Board, Greater Battle Creek Watershed Working Group, AquaTerra Consulting, Syblon Reid, Michael Love and Associates, Tehama Environmental Solutions, NV5, RCD of Tehama County, David Gamon, April Gamon, John Gammon and Donnette Thayer.

Learn More

You can read more about CalTrout's Battle Creek - Eagle Canyon project here.

Learn more about CalTrout’s involvement with the Battle Creek Hydroelectric Project and dam removal in our 2022 Dams Out Report.

About the Author:

Damon was introduced to the importance of conservation at a young age in the front of his dad’s canoe during wilderness river expeditions. This spark led to a passion for exploring wild rivers around the world and a career dedicated to conserving the species that rely on them.

His work has focused on bringing people and science together to solve complex fish conservation issues across California for the past 15 years. These efforts have resulted in the implementation of projects that benefit fishes and the publication of 25 peer-reviewed journal articles covering a diverse range of fisheries management issues. In 2020, his work was recognized by the California-Nevada American Fisheries Society with the Distinguished Professional Achievement Award. He holds a Master of Science degree in Fish Biology from Humboldt State University where he studied under Dr. Stewart B. Reid and Andrew P. Kinziger..