A River Reborn: One Year After Klamath River Dam Removal

The Klamath River Sees Dramatic Improvements in Water Quality and Salmon Repopulate Historical Habitat

This October marks the first anniversary since the removal of the four lower Klamath dams, and scientists, advocates and Tribes are celebrating dramatic ecological improvements for the Klamath River. Ongoing scientific monitoring, which started years prior to dam removal, has enabled the documentation of significant advances in water quality, water temperatures, and the rapid return of native salmon populations to previously blocked habitats.

"The Klamath is showing us the way. The speed and scale of the river’s recovery has exceeded our expectations and even the most optimistic scientific modeling, proving that when the barriers fall, nature has an incredible power to heal itself," said Barry McCovey Jr., Director of the Yurok Tribal Fisheries Department.

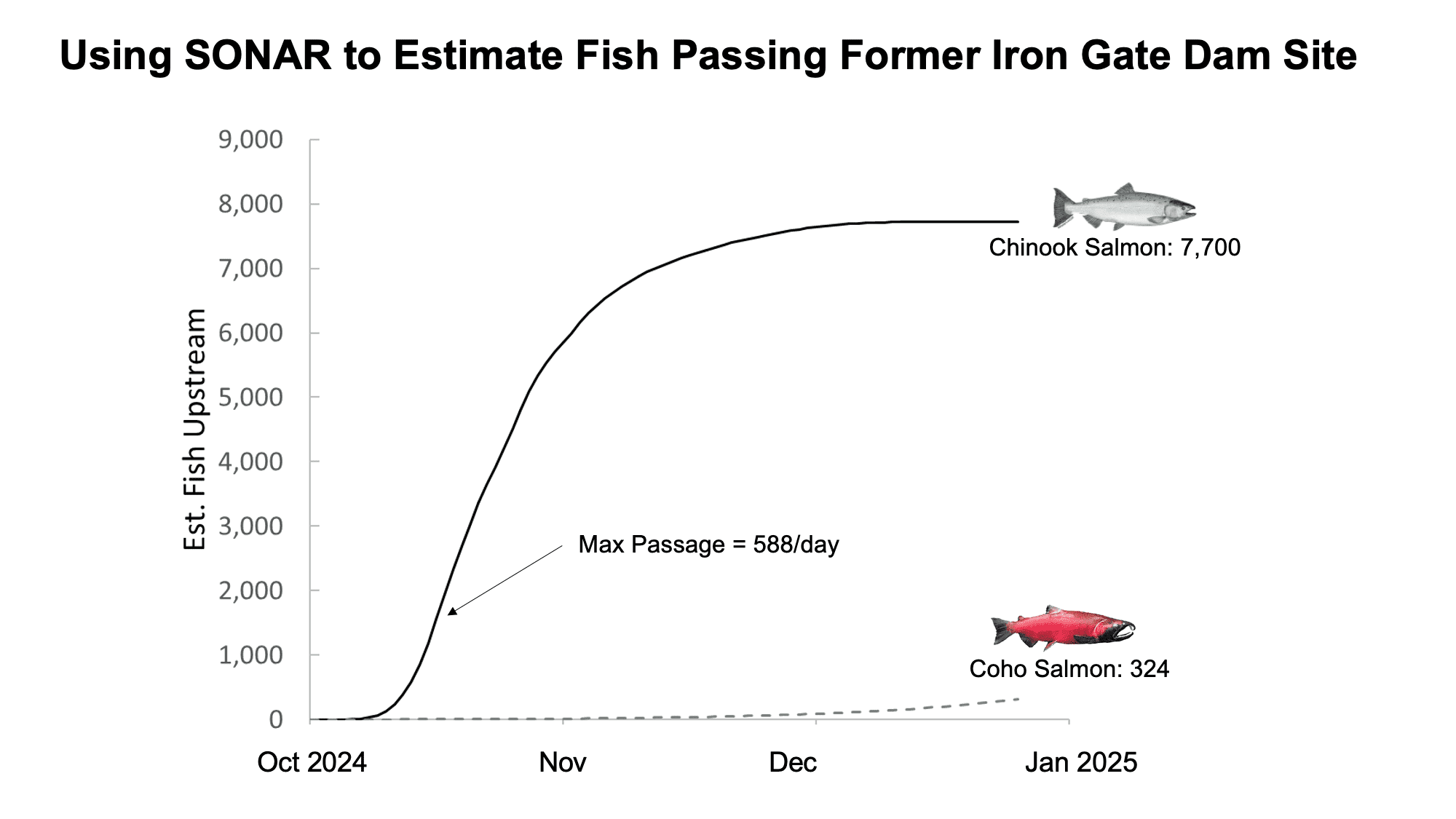

News of fish passing the former dam sites came the same week as the project's completion in early October 2024. While scientists were actively monitoring fish movements and spawning activity in the weeks and months following the restoration of natural flows to the river, it took several months of analysis to finalize specific data related to fish activity above the former dam sites. We now know that more than 7,700 Chinook Salmon swam upriver of the former Iron Gate dam site (the lowermost dam in the system) last fall to access habitat previously blocked by the dams. This number comes from a combination of monitoring techniques, including the use of SONAR, spawner surveys, and redd counts. This year the monitoring continues, and salmon have made it over the Link River Dam into Upper Klamath Lake.

“This is one of the most collaborative and comprehensive restoration studies ever undertaken with agencies, Tribes, and NGOs all coming together to monitor the recovery of the Klamath River salmon post-dam removal,” said Damon Goodman, Shasta-Klamath Director for California Trout. “What we witnessed was extraordinary—the river came back to life almost instantly, and fish returned in greater numbers than anyone imagined.”

Perhaps the most immediate and vital sign of the river's healing is the dramatic improvement in water temperature—a crucial factor for the Klamath's ecosystem. The dams and their reservoirs created artificially warm water temperatures in late summer and fall, when fish were returning to the system to spawn, and excessively cold water in the spring, when juvenile salmon out-migrate to the ocean. Ongoing monitoring of water temperatures both pre- and post-dam removal shows that temperatures have returned to a more natural regime that provides improved conditions for salmon during adult spawning migration and juvenile outmigration.

Hand-in-hand with this temperature recovery is a demonstrated monumental improvement in water quality, especially the precipitous decline of harmful algal blooms (HABs) and their associated microcystin toxins. Data collected by the Karuk Tribe since 2006 shows a powerful recovery: while 58% of samples below the former dam once exceeded public health limits, post-dam removal, 100% of water samples have tested within safe limits for people and wildlife. This combination of cooler, cleaner water is creating a resilient, thriving future for both fish and people.

“Since the dams were removed, temperature, algae, and dissolved oxygen levels have all dramatically improved,” said Toz Soto, Senior Policy and Research Advisor for the Karuk Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources. “The process of removing the dams created temporary water quality impacts as sediments impounded by the dams were mobilized through the system. When we look back at the data over the last year, we see that those short-term impacts were worth it, and the immediate improvements to the system are clearly documented in the data collected by the Karuk Tribe and others.”

The first year of a dam-free Klamath River demonstrates a powerful trajectory towards salmon recovery and an ecosystem with significantly improved health with significant cultural and community benefits for Tribes and others in the region.

About the Klamath River Salmon Monitoring Program

In fall 2024, CalTrout and our partners installed a SONAR fish counting station at the entrance to newly reopened habitat on the Klamath River. For the first time since Iron Gate Dam’s construction in 1964, anadromous fish could return upstream of the removed dam. The SONAR recorded more than 9,600 fish crossing this historic threshold, marking the beginning of population reestablishment, and we estimate 7,700 of those fish were Chinook salmon.

How does SONAR work?

The camera uses sound waves to generate movie-like imagery of passing fish on a continuous basis. Our team of scientists analyzes the camera’s recordings considering several factors including fish size and time of movement to discern that most of these are likely Chinook salmon or steelhead! This SONAR camera provided the first evidence of fish migrating into newly reopened habitat just days after dam removal construction wrapped up.

Following the Fish Through A Combination of Methods

In addition to SONAR imaging, the monitoring program employs methods including netting, radio telemetry, and spawner surveys. Netting documents fish species assemblages (variety and abundance of a fish species in a specific area), age, length, and genetic information and allow the team to attach tags to fish. Radio telemetry helps track fish migration into the 400 miles of newly re-opened habitat. Spawner surveys provide information on fish nesting locations. Together, these methods follow the fish to uncover how they are responding to dam removal and inform how to focus future restoration efforts. Last year, tangle netting and surveys by tribal, state, and federal partners confirmed the presence of Chinook salmon, coho salmon, steelhead, and Pacific Lamprey in California and Oregon waters.

The project team consists of dedicated individuals representing the Karuk Tribe, Klamath Tribes, Yurok Tribe, Ridges to Riffles, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, NOAA Fisheries, Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Cal Poly Humboldt, U.C. Davis, U.S. Geological Survey, Keith Denton and Associates, Resource Environmental Solutions, and CalTrout. The monitoring program is funded by Humboldt Area and Wild Rivers Community Foundation, Bella Vista Foundation, Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and NOAA Fisheries.

Applying AI to Fish Counting

This year, we launched a partnership with MIT and CalTech to integrate artificial intelligence (AI) into our fish counting station. By applying advanced machine learning, we’re building a platform that delivers near real-time updates on the number of fish passing — dramatically improving the speed, accuracy, and accessibility of data for managers and partners.

Understanding how fish respond to dam removal is essential for shaping future restoration and fisheries management efforts—both in the Klamath River basin and globally. The integration of SONAR fish counting station and AI will accomplish three key things. First, it will provide timely, high-quality data on adult salmon returning to newly opened habitats. Second, it will support tribal, state, and federal partners in making informed decisions. Finally, it will accelerate learning from the world’s largest dam removal project, creating a model for river restoration worldwide.

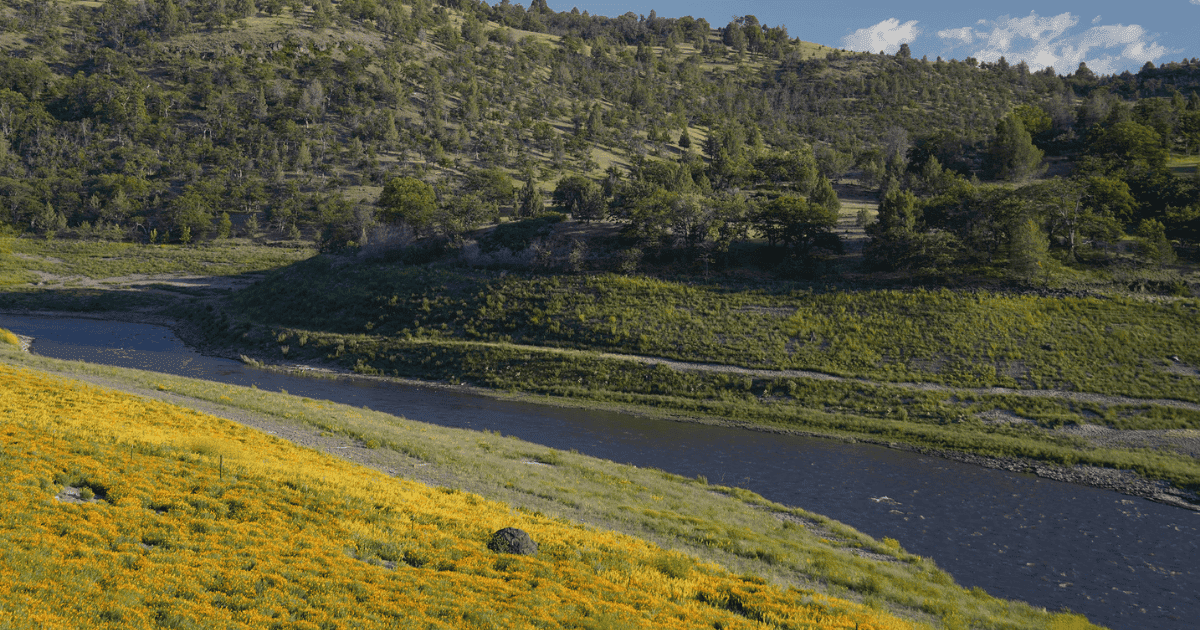

Cover Photo Credit: Dylan Aubrey, Yurok Tribe