CalTrout and PG&E Complete Bay Area Fish Passage Project, Reopening Alameda Creek to Migrating Salmon

CalTrout and PG&E Complete Bay Area Fish Passage Project, Reopening Alameda Creek to Migrating Salmon

With the gas pipeline lowered and over 20 miles of habitat reconnected, Chinook salmon are already reaching upstream stretches for the first time in decades.

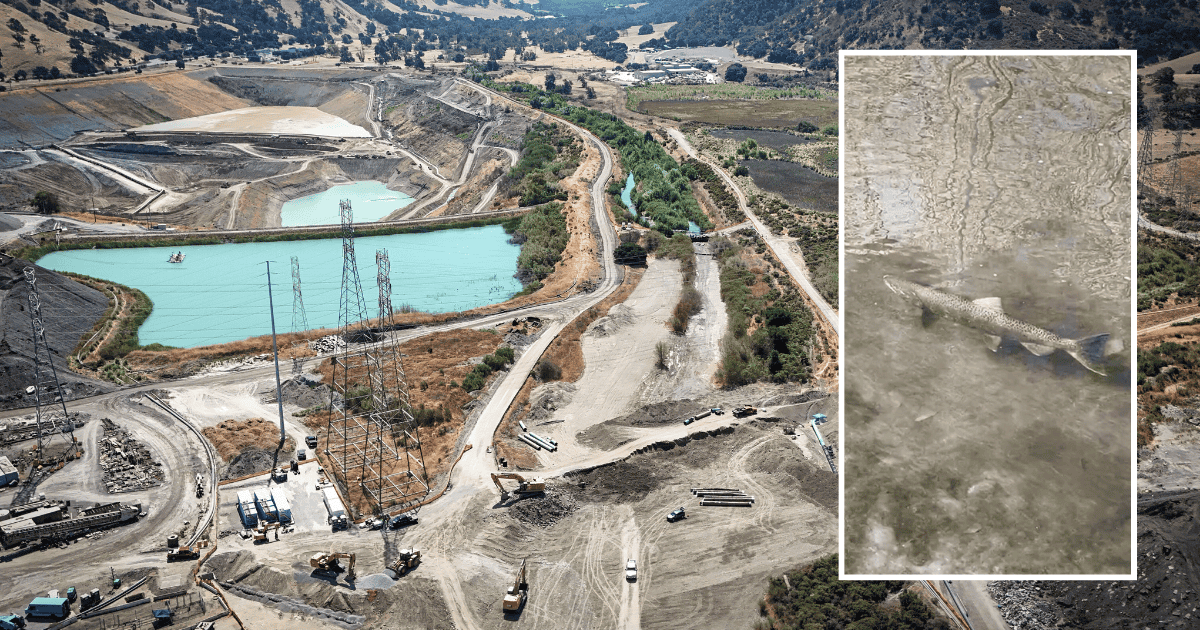

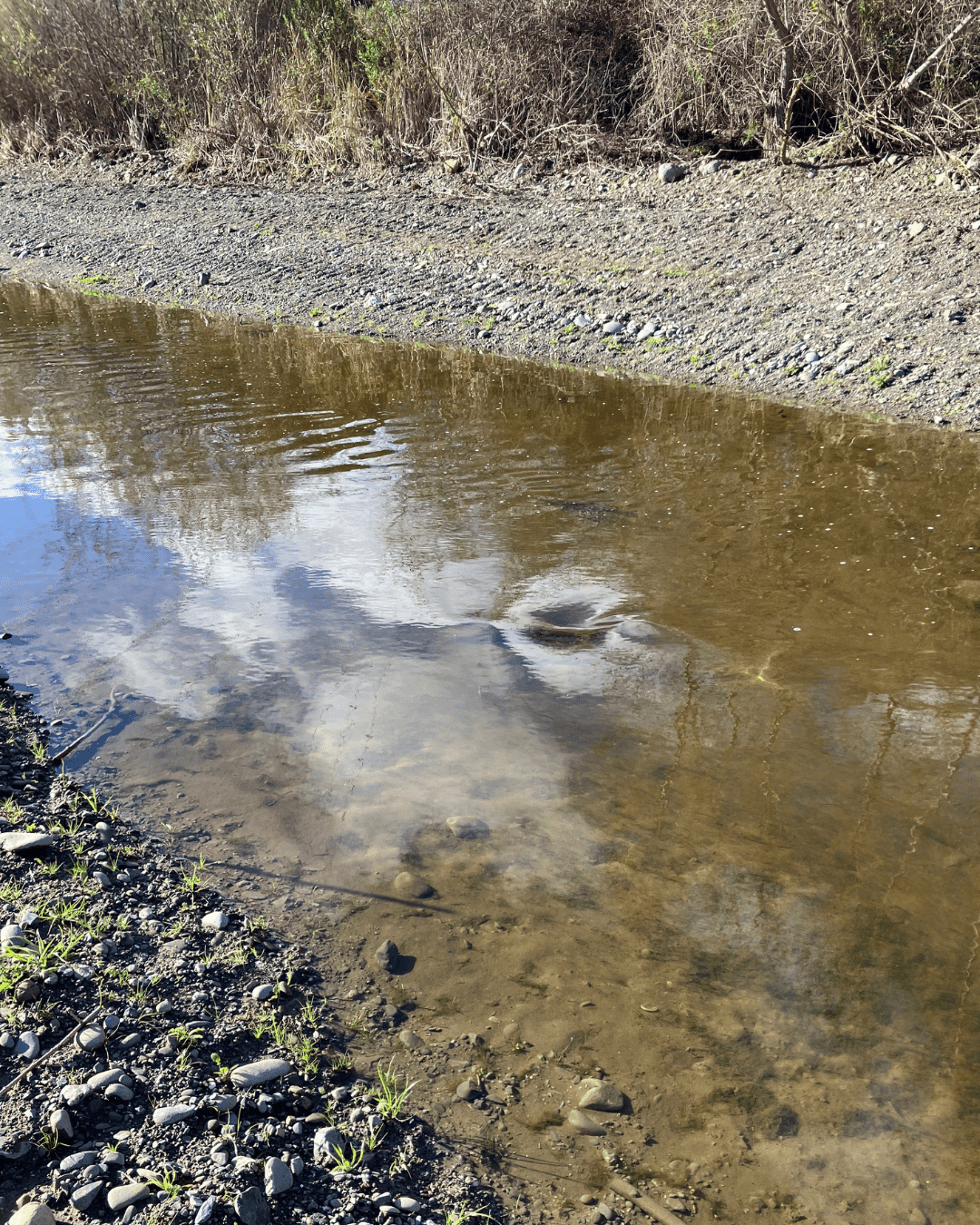

Earlier this month, California Trout (CalTrout) and Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) wrapped up construction on a project that remediated the last unnatural barrier to fish passage on mainstem Alameda Creek, the largest local tributary to the San Francisco Bay. As of November 19, Chinook salmon have already been observed migrating above the former barrier accessing habitat that has been largely unavailable for over 70 years. Alameda Creek historically produced large numbers of California Coast Chinook salmon and Central California Coast steelhead in the South Bay, but today many of the Bay Area’s native fish are struggling and vulnerable to extinction if current trends persist. The project connected more than 20 miles of stream including quality spawning habitat in the upper watershed to Chinook salmon and steelhead.

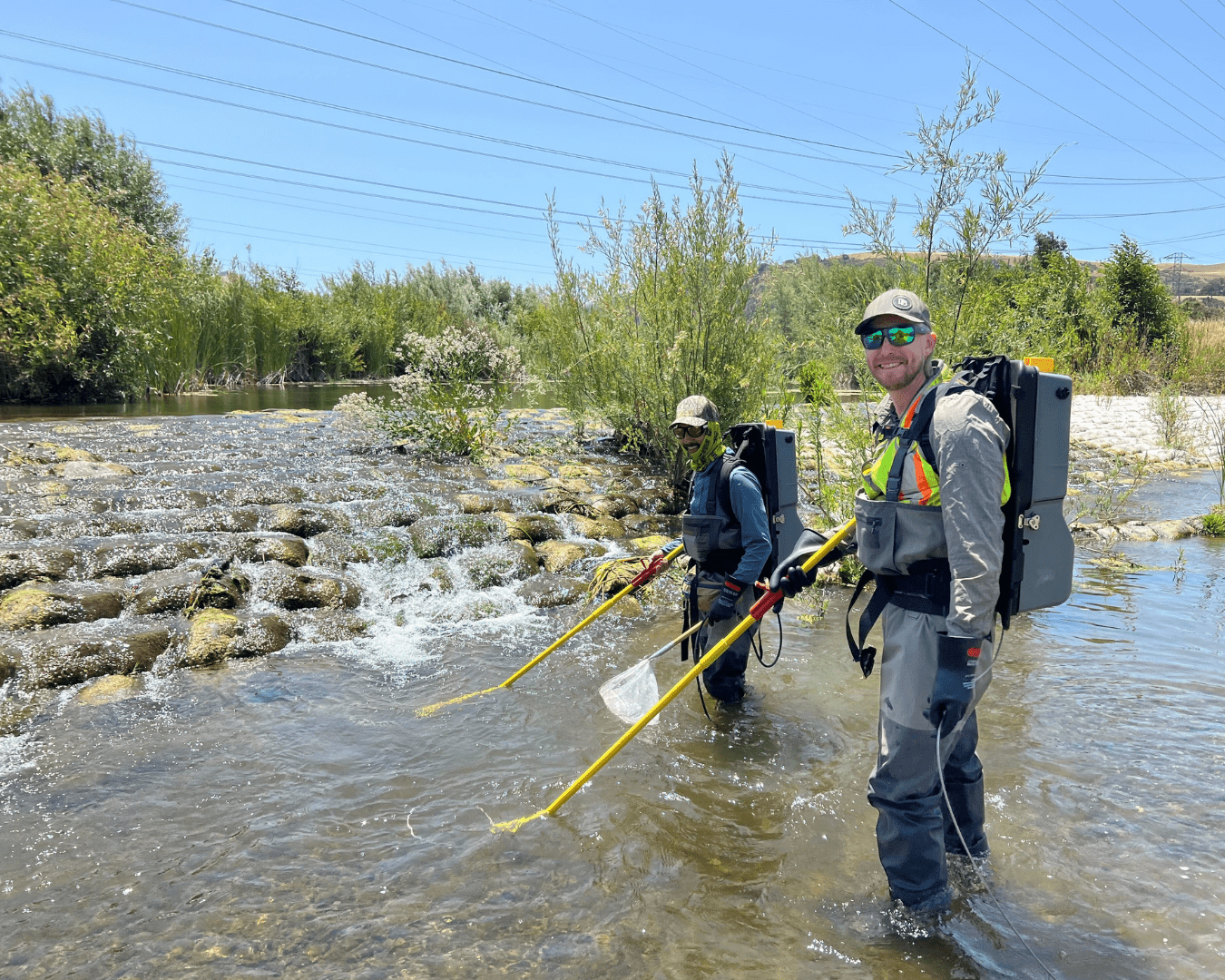

On November 19, team members with Sequoia Ecological Consulting, CalTrout’s biological consultants, documented two fish between 12 and 24 inches long just upstream of the former barrier location. These fish were identified as Chinook salmon. Based on best available records, this is the first time salmon have volitionally accessed this part of the watershed since the 1950s.

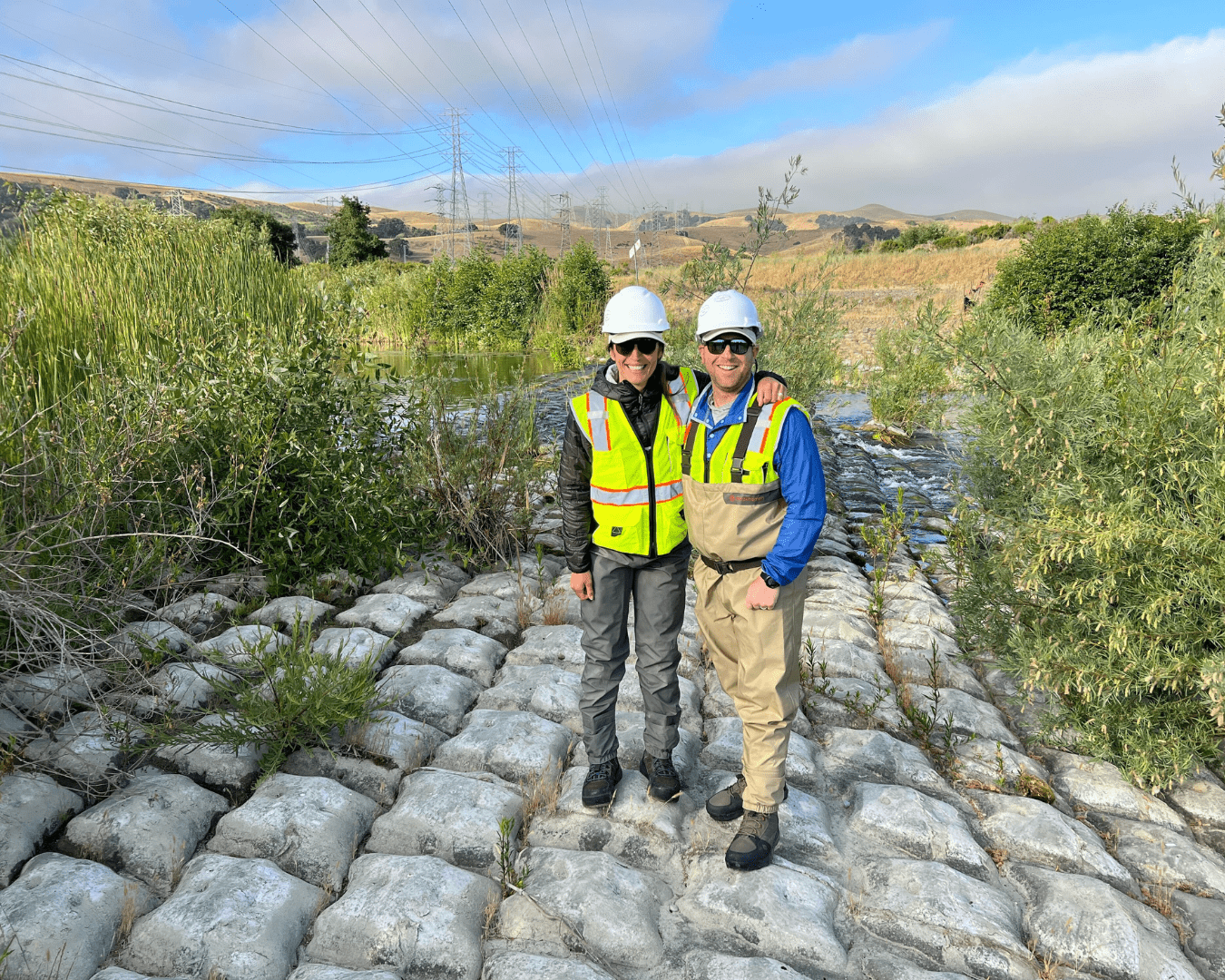

“We just wrapped up construction, and the fish are already finding their way home! It’s incredibly gratifying to see these incredible species reclaim crucial habitat that they have been locked out of for decades,” said Claire Buchanan, CalTrout Central California Regional Director. “This project remediates the last major barrier in mainstem Alameda Creek, and it was only possible after decades of advocacy and planning by the Alameda Creek Alliance, PG&E, Applied River Sciences, SFPUC, and others.”

The remediated barrier was created by a major gas pipeline in Sunol Valley upstream (or south) of the Interstate 680 overpass. Owned by PG&E, the pipeline was covered in a protective layer of concrete, known as an erosion control mat, which protruded up into the creek. This made the creek impassable to fish during most stream flows. During wet winters, flows were high enough to pass fish, but as California’s cycle of drought and deluge continues, resolving this last barrier to fish passage ensures fish access upstream and downstream, regardless of species, life stage or size, and whether it’s a wet or dry year.

To address this fish passage barrier, PG&E’s gas pipeline was moved downstream approximately 100 feet and lowered about 20 feet beneath the creek bed. Burying the pipeline removed the risk of erosion and the need for an erosion control mat. Following the pipeline relocation and the erosion control mat removal, the channel was regraded and revegetated with native plants.

"We're so excited to play a part in the historic return of steelhead trout and Chinook salmon to Sunol Valley. Being good stewards of the environment is one of our priorities as a company and witnessing that stewardship pay dividends in a local ecosystem is incredibly gratifying," said PG&E Vice President of Gas Construction Kevin Armato. "We’re looking forward to seeing these fish and other species thrive for generations to come.”

The channel restoration design plans were developed by Applied River Sciences. The pipeline lowering plans were developed by PG&E. Construction was conducted by Hanford ARC and Michels Corp, PG&E’s contractors. Sequoia Ecological Consulting provided the biological resources support, while Stantec Inc. provided cultural resources support for the project. The project is cost-shared by PG&E, NOAA Fisheries via federal grant funds, and a private foundation. While construction is complete, revegetation and final site cleanup will continue through mid-December.

The site of the former barrier is located on San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) property in Sunol Valley, upstream from where the agency previously removed the Sunol and Niles dams in 2006 and downstream of a fish ladder constructed by 2018 at the Alameda Creek Diversion Dam.

“The SFPUC and our partners on Alameda Creek have worked for more than 20 years to address migration barriers and enhance stream flows in the Alameda Watershed,” said Dennis Herrera, General Manager of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. “Because of these collective efforts, we are starting to see substantial increases in fish moving upstream and downstream within the watershed. This is a proud moment for all of us.”

Alameda Creek flows from remote Packard Ridge in the Diablo Range east of San Jose, for more than 40 miles until it reaches the city of Fremont where the lower 12 miles of creek are corralled through a flood control channel into San Francisco Bay. The creek flows by and through hundreds of Bay Area residents’ backyards and is bisected by Highways 880 and 680 and paralleled by Highway 84. Over the past century, the watershed experienced intense urbanization including the construction of three major dams and reservoirs.

Until recently, the entire watershed was inaccessible to anadromous fish (besides lamprey which are able to sucker their way over some barriers). In 2022 and 2023, former barriers at the BART weir and inflatable bladder dams in Fremont, eight to ten miles upstream of where Alameda Creek enters the Bay, were made passable for fish due to newly constructed fish ladders by the Alameda County Water District and after years of advocacy by the Alameda Creek Alliance. The newly constructed fish ladders enabled Chinook salmon and steelhead to migrate through the lower creek into Niles Canyon and access parts of the upper Alameda Creek watershed for the first time in over fifty years.

The Alameda Creek Fisheries Restoration Workgroup, formed in 1999, brought together water and land management agencies, regulatory agencies, the Alameda Creek Alliance, local fly-fishing groups, and nonprofits. The workgroup cooperatively started to address fish passage in the watershed from funding to permitting to implementation. Together, the group has implemented fish passage projects, including removing dams and constructing fish ladders, that remediated 17 former fish passage barriers throughout the watershed. These efforts were undertaken by workgroup members, including the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC).

“The return of salmon heralds hope for more healthy ecosystems and these charismatic fish are excellent ambassadors for protecting and restoring our local watershed,” said Jeff Miller, Director of the Alameda Creek Alliance. “We’re seeing results from two decades of restoration projects and we hope Alameda Creek will have an outsized impact on the recovery of steelhead trout in the region. It’s profoundly gratifying to see watershed residents and local water agencies taking pride in bringing back native fish and wildlife.”

For more information about the Sunol Valley Fish Passage Project, please visit https://caltrout.org/projects/sunol-valley-fish-passage-project-alameda-creek.