Ghost-Hunting for Salmon and Steelhead in Santa Cruz

by Will Ware, CalTrout Bay Area Project Coordinator

May 2024

Ghosts of Past & Present

Monitoring salmon and steelhead is like ghost-hunting. Despite declining population numbers, these spawning salmonids still run in the memories of communities along coastal California streams. These fish support the livelihoods of diverse people including tribes, commercial fishers, and recreational fishing businesses. Claire Buchanan, Bay Area Senior Project Manager, captured the sentiment when she said “steelhead are like ghosts” as she described how they often migrate up and down creeks undetected under the cover of darkness and murky waters after storms. In the Santa Cruz Mountains, at the southern edge of where salmon spawn along the West Coast, sightings of critically endangered coho salmon are rare and threatened steelhead are seen less than they once were. Conservationists are working to conjure more of these fish back into the Santa Cruz Mountains.

The two largest watersheds in the Santa Cruz Mountains range are the Pescadero Creek and San Lorenzo River watersheds that once supported strong spawning runs of coho salmon and steelhead. These watersheds also supported populations in nearby creeks with “spill over” of individuals that crossed boundaries. Time shaped these two drainages in both similar and distinct ways. Logging thinned the old-growth redwood forests that covered the upper portions of the mainstems and tributaries as flood control measures reduced their tidal prisms along the coast. The lower portions of the Pescadero Creek watershed largely became agricultural lands while the lower portions of the San Lorenzo watershed largely became urban and suburban lands. Still, both watersheds are crucial to recovering salmon and steelhead populations to some semblance of their historic highs and de-list them from the Endangered Species Act.

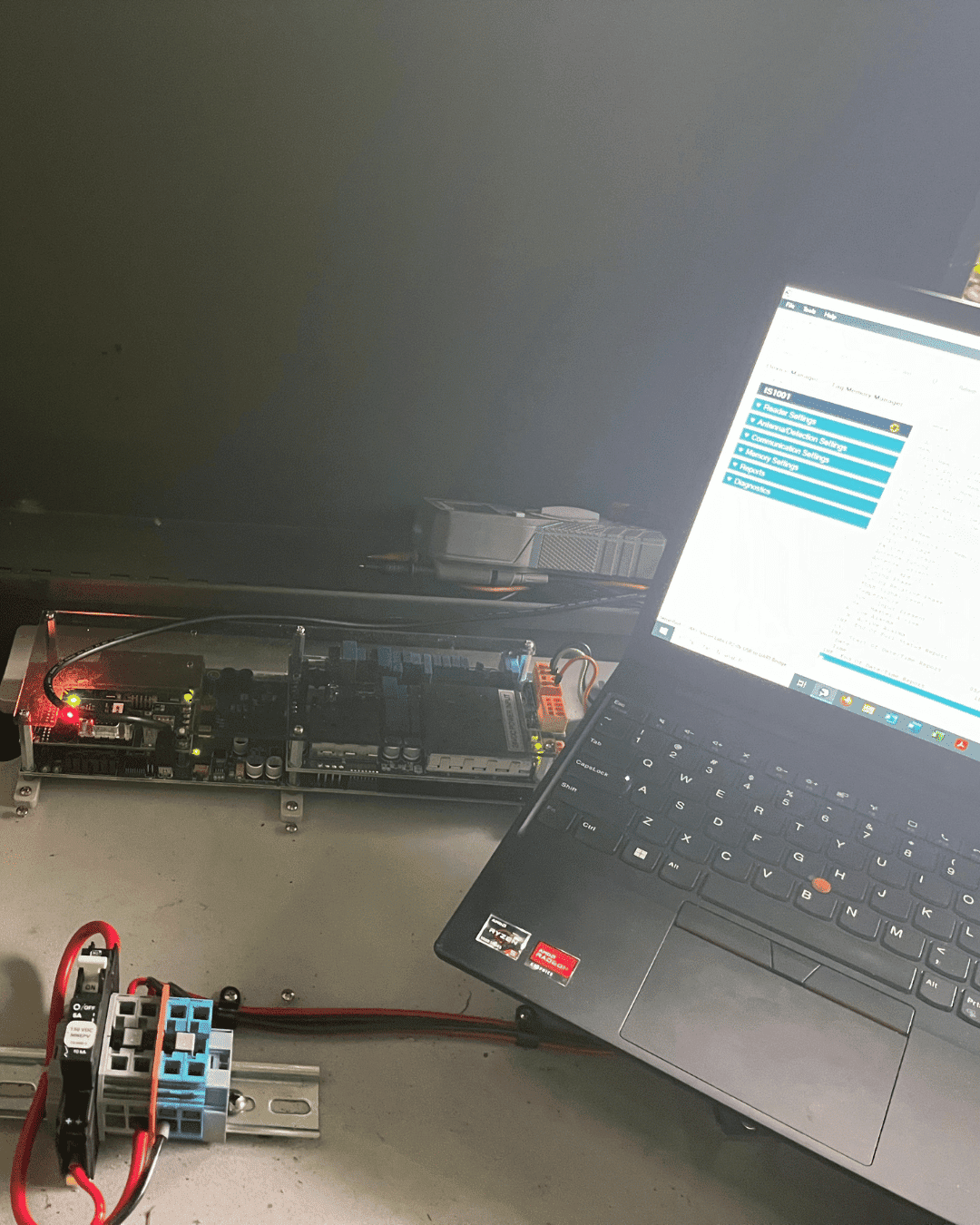

Biological monitoring indicates the success of population recovery actions via various tools that sample phantom fish. Backpack electrofishing units, which resemble Ghostbusters proton packs, are used to catch fish in shallow streams. Handheld readers, which resemble psychokinetic energy readers, detect passive-integrated transponder (PIT) tags placed in migratory fish. PIT tags are a common way to study the movements of coho salmon and steelhead. Tags are inserted into the abdominal cavities of fish. The unique PIT tag identification codes are scanned and recorded by handheld readers before fish are released. PIT tags are then passively detected as fish swim past PIT tag antennas that span stream channels at opportunistic locations. These antennas operate as fish counters that transmit the uniquely identifiable tag codes, date, and time of detections to computer boards where data is stored and retrieved for analysis. Results are used for a variety of applications such as determining how many individuals survive in a certain area, tracking how relative abundance changes over time, inferring habitat use, determining the reasons behind individual fish movements, and inferring whether unique movement patterns are expressions of “life history” such as spawning at specific times of the year.

"PIT-ting It" Together

PIT monitoring requires collaboration across the boundaries that coho salmon and steelhead swim across. In 2019, Patrick Samuel, Bay Area Director, launched a pilot study with Trout Unlimited and California Department of Fish and Wildlife that tracked the individual movements of coho salmon and steelhead near the town of Pescadero in San Mateo County. This sparked the ongoing Pescadero Creek Watershed PIT Project between the aforementioned partners and NOAA Restoration Center, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center, California State Parks, San Mateo County Parks, and the San Mateo Resource Conservation District. The Science Center used PIT detections and genetic sampling to show that coho salmon and steelhead stray between watersheds along California’s northern and central coast. Salmonids often stray between coastal streams and rivers in San Mateo and Santa Cruz counties, which means that fish move between the Pescadero Creek and San Lorenzo River watersheds.

This is why, at CalTrout, I launched a pilot PIT study of salmonid migrations in Branciforte Creek, the lowest tributary to the San Lorenzo River, located near downtown Santa Cruz. The purpose of this study is to determine if salmonids from the San Lorenzo River and nearby streams use natural habitat in Branciforte Creek upstream of the flood control channel. PIT detections are like puzzle pieces that can form a picture of when steelhead and coho salmon use the creek. If tagged individuals swim up Branciforte Creek, they will pass through two PIT antennas that span the stream channel. The paired antennas will indicate swimming direction via consecutive detections. There is currently one antenna at the study site that took months of trial and error to build out of hardware store materials, install, repair as spring storm flows passed, recalibrate, and continuously operate. Although the process changes with each antenna, my lessons learned will streamline the deployment of the second antenna at the site. Both antennas will be made from loops of flexible wire that spans the creek like a stretched donut whose sides are tied to tried and the bottom half is staked in the streambed so that the half top floats to naturally adjust to changing water levels. This is important since only part of the channel is wet as water drops to summer base flows yet streambanks may have flash floods in the winter. This method was originally designed by Dr. David Boughton and Dr. Haley Ohms at the Science Center in the Carmel River and it is useful for our coastal watersheds with flashy flows.

The Branciforte Flood Control Channel poses a barrier to fish migration from the lower San Lorenzo River up through the first mile of the creek. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers installed the flood control channel in 1955 to reduce flood risk to the City of Santa Cruz by quickly passing storm flows on Branciforte Creek. Unfortunately, this channel became a barrier to upstream salmonid migrations because it either funnels water too fast for fish to pass at high flows, the low flow channel gets clogged with sediment, or birds can easily pick out fish moving through.

The City recently contracted engineers at Environmental Science Associates to evaluate fish passage and design a solution to improve movement through the concrete channel. ESA engineers developed hydrologic models which predicted that only adult salmonids can swim upstream through the channel during a narrow range of stream flows. The winning fish passage solution combines “rocks in a box” where boulders slow storm flows through the channel enough for fish to move upstream in winter with “culvert cubbies” designed to provide piscine pit stops. The Branciforte PIT antennas are above the flood channel as the City works to secure funds to implement this fish passage solution. This will provide baseline data on salmonid migrations to determine if and when fish can make it upstream. The baseline data will then be compared post-project to determine efficacy of these passage improvements and help us understand how salmon and steelhead utilize this historically important spawning tributary.

Opportunities to detect tagged salmonids in Branciforte Creek stem from multiple monitoring efforts by numerous partners in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Wild, juvenile steelhead are PIT-tagged each summer and fall in the lower reaches of Pescadero Creek, Butano Creek, Laguna Creek, and the San Lorenzo River by permitted biologists from the California Department of Fish & Wildlife and the City of Santa Cruz that lead other conservation professionals and volunteers. At different times of the year, ecologists from the Science Center also PIT-tag steelhead from the wild to research them and release coho salmon from conservation hatcheries into several streams to boost populations. These salmonids naturally stray into nearby streams as both juveniles and spawning adults, and these variable migration patterns support “life-history diversity.” This increases the likelihood of detections in Branciforte Creek as tagged salmonids swim from elsewhere. Life-history diversity supports salmonid population recovery by promoting resilience to changing environmental conditions such as droughts and post-fire debris flows that reduce spawning and rearing habitat.

Calling Back Coho

Branciforte Creek historically attracted wild spawning runs of returning coho off the mainstem San Lorenzo River. It offered a relatively easy swim over six miles of low-gradient stream habitat in perennial, cold water fed by springs and shaded by old-growth redwoods. Younger trees now comprise the riparian forest, with Branciforte Creek still draining through redwood ridges, meandering through a rural valley, splitting suburban backyards, and then straightening into the one-mile-long concrete flood control channel.

Given the history of this stream and others, conservationists endeavor to make Santa Cruz “coho country” once more. In the 2010s, homeowners share stories of spawning steelhead in rocky riffles in Branciforte Creek above the flood control channel. During this period, Santa Cruz County biologists sampled juvenile steelhead with Ghostbusters-style backpack electrofishing units, and volunteers for the Monterey Bay Salmon and Trout Project used handheld PIT tag readers to scan returning adult steelhead for tags as they moved through a fish ladder in Felton. The Resource Conservation District of Santa Cruz dismantled dead-beat dams in 2017 and 2022 to restore access to historical spawning grounds. They continue planning to knock down more dams like dominoes as the County plans to check off its dam hit list along the mainstem San Lorenzo River.

Opportunities to detect tagged salmonids in Branciforte Creek stem from multiple monitoring efforts by numerous partners in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Wild, juvenile steelhead are PIT-tagged each summer and fall in the lower reaches of Pescadero Creek, Butano Creek, Laguna Creek, and the San Lorenzo River by permitted biologists from the California Department of Fish & Wildlife and the City of Santa Cruz that lead other conservation professionals and volunteers. At different times of the year, ecologists from the Science Center also PIT-tag steelhead from the wild to research them and release coho salmon from conservation hatcheries into several streams to boost populations. These salmonids naturally stray into nearby streams as both juveniles and spawning adults, and these variable migration patterns support “life-history diversity.” This increases the likelihood of detections in Branciforte Creek as tagged salmonids swim from elsewhere. Life-history diversity supports salmonid population recovery by promoting resilience to changing environmental conditions such as droughts and post-fire debris flows that reduce spawning and rearing habitat.

Inspiration flows further than water as memories of spawning salmonids run in our collective consciousness.

Key to the Future

Salmon and steelhead are “keystone species” that uphold diverse communities and ecosystems along the West Coast of the Pacific Ocean. Social-ecological systems can crumble like archways as these iconic fish leave their historic habitats. However, coho salmon and steelhead return to their historic spawning grounds when barriers to entry are removed. We monitor for evidence of these ghost fish using PIT tags and antennas. Each data point is a word of a story that informs salmonid population recovery efforts by a collaborative group of agencies, nonprofits, landowners, and other community members across the Santa Cruz Mountains. CalTrout is thrilled to support them in conjuring coho salmon and steelhead back in greater numbers.

2 Comments

Thanks so much for this article and for the work you are doing on Branciforte creek. I live up Branciforte Creek and every once in while catch a glimpse of a steelhead or coho ghost up in my neck of the woods!

I’m amazed, I have to admit. Rarely do I encounter a bloog that’s equally educative and amusing, and let me tell you, you have hit the

nail on the head. The issue is something too few people are speaking intelligently about.

Now i’m verey hppy that I stumbled across this inn my

search foor something regarding this. https://ukrain-forum.biz.ua/