How Can California’s Iconic Hat Creek Be Restored?

Hat Creek (image courtesy Val Atkinson)

Once an iconic California fishery, Hat Creek needs help. Here’s what we’ve got in mind.

Hat Creek in better days (image courtesy Val Atkinson)

In the 1960s, California’s Hat Creek was a mess; overfished and overrun by non-game species, anglers could legally kill ten of its trout per day.

By 1972, a young conservation group named CalTrout succeeded in restoring Hat Creek’s habitat, reduced harvest to two fish per day, and had it declared California’s first Wild Trout Area.

By 1983, the success of CalTrout’s Hat Creek project was apparent; fish counts were estimated at 5,000 fish per mile, the weed beds and hatches were stunning, and anglers traveled from all over the west to fish it.

By any measure, it had become California’s most iconic fishery.

But even as Hat’s reputation soared, the 50,000-80,000 tons of fine volcanic sediment that would eventually strangle it was becoming apparent in aerial photos.

A light-colored smear below Powerhouse Riffle #2, the sediment plug — which for decades migrated down Hat Creek like a slow-moving wave — suffocated Hat’s rich beds of aquatic vegetation and the insect life that depended on it.

When the bugs and the cover went away, so did Hat Creek’s fabled trout.

Carbon Bridge sediment plug, 1991

Worsening matters were the non-native muskrats (released into the wild when a nearby fur farm went bankrupt). They burrowed under Hat Creek’s banks, which promptly collapsed. That had the effect of widening and shallowing Hat Creek, compounding its problems.

Cattle grazing also denuded the riparian corridor and speeded the collapse of the banks.

Recently — with the tail end of sediment plug finally starting to clear Hat Creek’s upper stretches — fish populations had plummeted to an estimated 1,000 fish per mile — approximately 1/5 their peak population.

Hat Creek — an iconic fishery which once drew anglers from literally around the world — has once again fallen on hard times.

Muskrats undermine banks at Hat Creek.

What’s Next?

Hat Creek remains compromised, but there are encouraging signs. Aquatic plants have begun reappearing at the tail end of the sediment plug and the cattle are gone.

The luxuriant hatches of previous decades have largely disappeared (longtime local and CalTrout Board Member Dick Galland recalls fishing 16 distinct hatches during Hat’s better years), and many speak fondly of Hat Creek’s “Golden Age” as if it was gone forever.

Intent on recovering Hat Creek’s iconic status, CalTrout has created a new restoration plan, the goal being a return of stable, sustainable fish populations to Hat Creek.

Most encouragingly, PG&E — who owns the land surrounding Hat Creek — recognizes its value to anglers, and is working with CalTrout and other partners to restore Hat Creek.

Perhaps Hat’s Golden Age isn’t behind us.

Working Plan

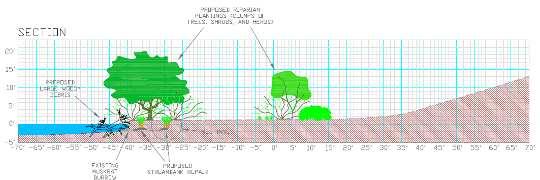

Bank stabilization drawing (click image for larger version of restoration drawing)

CalTrout’s draft recovery plan — developed in conjunction with PG&E, the California Department of Fish & Game and the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences — focuses on six key areas:

-

A program designed to monitor Hat Creek’s status and progress.

-

Replanting 6.3 acres of Hat’s riparian corridor with native plants (including alders and willows, which disappeared when the cattle arrived).

-

Adding large woody debris (typically trees with root balls still attached) to mimic the trees which would have fallen into the river had cows not intervened. These provide exceptional instream habitat for bugs, juvenile trout and large trout alike.

CalTrout’s Drew Braugh on restoration

-

Moving the Carbon Bridge parking lot away from the river’s edge to minimize angler impacts.

-

Constructing a trail around Hat Creek (Wild Trout Area), including two pedestrian overpasses (minimizing angler impacts on streamside vegetation).

-

Stabilizing the banks and hardening them against muskrat burrows.

“We’re encouraged to see some aquatic vegetation appearing at the tail end of the sediment plug,” said CalTrout’s Hat Creek Project Manager Drew Braugh.

“If we can build up the instream habitat — mostly by using large woody debris to provide cover for fish and a place for aquatic vegetation to root — and address a few other issues, we can get Hat Creek back on track.”

The Future

Note that dredging is not a part of the restoration plan; there isn’t enough material left to justify the disruption, and the presence of an endangered sucker likely renders dredging untenable.

More importantly, biologists believe Hat Creek’s submerged weed beds will reappear if given a chance to reestablish themselves.

Right now, the Hat Creek restoration plan remains just that — a plan. CalTrout is actively seeking funding to undertake Hat’s restoration (we should receive word on one funding source by Fall of 2012).

In the meantime, we’re moving forward with the first steps in the process: permitting, finalizing the plan, and working closely with PG&E (who owns the properties).

Hat Creek was once California’s premier fishery, and with a little help, it can fish like the world-class fishery it once was.

CalTrout’s members, readers and interested parties should stand ready; we’ll no doubt ask you for a show of support sometime in the future, if only to convince our partners that Hat Creek still means something to California’s fishermen.

16 Comments

I strongly doubt this fishery has 1000 fish in the entire system. We’re squawfish and suckers included in the estimate? It is disgusting that the fishery was allowed to fall into the state it is currently in.

The population estimate was determined by visual counts using multiple divers, and the number refers to trout, not other species.

As for Hat Creek’s current current state, there really isn’t much that can be done about an 80,000 ton sediment plug moving through the system (dredging isn’t really an option for several reasons), and we’re encouraged by the reappearance of aquatic vegetation at the tail end of the plug.

CalTrout’s restoration plan aims to address those things we can address (bank stabilization, instream habitat via woody debris, minimizing further muskrat and angler impacts, etc.). We’re hopeful — with a little help — Hat Creek will return to being a productive (world-class even) fishery.

We hope we can count on your support during those efforts.

As a fly fisherman, no aquatic plight has saddened more in CA than Hat Creek. I have watched it disintegrate the last decade and it really breaks my heart.

I support you, keep up the good work.

President Grizzly Peak Fly Fishers Berkeley CA

Obviously, Hat Creek is a huge problem. But it’s not your only issue in California to say the least. It’s safe to say that every body of water in California is negatively impacted by dams for power, irrigation and drinking water. Multiple sources of erosion and contamination are everywhere. So without the natural flushing that happens on a freestone river, you will ALWAYS have these problems as long as early 20th century infrastructure exists in these streams.

Perhaps your biggest challenge given extremely limited resources (money) is which one of these do you want to fix? I live in Lake Tahoe and we have pristine water flowing down the Truckee and there is good fishing here. But imagine if Donner Lake, Boca, Prosser and Stampede Reservoirs were not impounded but rather served as filtration for the river and spawning habitat for Lahonton Cutthroat Trout!!

I think Hat Creek is a nice nostalgic project but I would much rather see you guys spend our money on projects that have real potential on a grand scale. Because if you don’t think BIG now, you will have a lot more collapses on your hands.

Jim;

You’re right that we always have to apportion resources, but think we’re doing pretty well in that area. If you haven’t seen it yet, you’ll find a list of our 2012 projects here. You’ll notice we’re active in most major watersheds.

Hat is more than a nostalgia project to us; it once supported a lot of fish in a highly challenging fishing environment (something many of our members actively seek out), and we think — with a little help — it can do so again.

Just thinking about the needed resources for such a monumental task as outlined with the restoration of Hat Creek. Of course, it’s going to require money “raised” in some manner, but where will the bulk of it likely come from? Main secondary source?

Additionally, it will certainly require “man power” . I understand the obstacles to some degree of having just anybody physically work and get involved, but I would love to be offered to be part of that. If anyone wants to know why I should , contact me and I’ll explain further!

i remember the glory days myself. 30+years ago. there are some good ideas put forward to improve the creek. the idea of two pedestrian bridges is silly and crazy expensive. how about trapping muskrats? a bounty could be instituted. curious how fall, hat, and yellow have all plummeted.

You know I want my ashes spread on Hat, and I think the demise of the fishery began when Cal Trout put in all the trees to divert flows. The browns soon ceased to be. While there are more and bigger rainbow in the stream now, I seldom take a brown over six or seven inches. In the late nineties my biggest brown ever came to a stonefly, it measured 26 inches, and was an old buck on his way out. I haven’t seen a fish recently even close to that. Last Spring an angler from WA took a 20 inch rainbow on a green drake just above the 299 bridge. This May in two nights I hooked several ‘bows in the 12 inch range, and not another angler. Ninety-nine percent of the presure in the riffle (I don’t think people know how to fish w/o a bobber), and then the stonefly hatch brings anglers to the riffles above the park. I truely believe that the fishing for bows was improved by the last round of improvements, while the brown population plummeted. I’m glad anglers think Hat is done, because I know it’s not—not nearly as bad as some say. I’ve fished it for almost forty years, and I think that last year was the best rainbow fishing I’ve had as far as average size and number of bows. I think the problem is angler skill and expectation. Hat fish are never easy except in the riffle with a bobber, and in all my years on it I only fished the riffle on my first trip. Too many maladroit anglers for my taste. If I can get five fish to eat, LDR three of those, and land one or two, I’ve had a great night.

rl

Thing is, browns are not native to North America and, though people like to catch them, they are in fact a kind of invasive species, just like brookies are west of the Mississippi. I wouldn’t be concerned about your catch rate on browns. The important point is that the creek is being given some TLC again.

Again Cal Trout needs to pay more attention to the actions of the Stewardship Council. They are in the process of transferring PG&E properties to non profits and or government agencies. The Hat Creek property will be transferred in the future to some entity other than PG&E. I feel that PG&E should retain ownership of this and other watershed properties. The transfers by law have to be property tax neutral to the counties, which mean that whomever owns them will have to pay property taxes, this and other ownership costs will prohibit habitat work, and/ or cause Hat Creek to have a fee to fish or use put in place. I believe that the public would be greater served by PG&E retaining ownership. after all they use this resource for the generation of power and the rate payers and stock holders owe it to the resource and the resource using public to maintain, and enhance those resources. Cal Trout needs to be more involved, the Stewardship Council, as a result of the PG&E bankruptcy has is receiving $10 million dollars per year for 10 years to give away PG&E property. Think about what could have been done to enhance the resource on PG&E properties if this money had been spent on Habitat and recreation enhancements and restoration.

Sediment is not the only problem at Hat Creek. Serious work and attention must be paid to the water flows into the creek.

I have seen the entire flow into this creek completely cut off.

My fishing partner and I began scooping up stonefly and assorted other nymphs and moved them too deeper water areas where hopefully some survived.

I am not sure what happened to all of the fish when all of the flow to the creek was cut off.

Having moved to Oregon from SFO 10 years ago, I had no idea that Hat Creek had these problems. I had always understood that place to be Valhalla for fly fishers. When I came here I took up fly fishing and have never put my rod down!

Here in Oregon, there are several examples of similar degradation, most of it man made, though. One of the great fishing comeback stories is the Metolius River, near Sisters, OR. 15 years ago it was an overfished, overplanted, undermanaged wild stream which appears fullblown from an enormous spring beneath a cinder cone. Today, thanks to concern and support from many fly fishing groups and enthusiasts, it is protected from hatchery plants and is planted with a lot of streamside vegetation and fallen trees to provide habitat for fish and bugs. It is also catch and release in the best parts of the river.

Today, it’s a premier place to fish and requires skill and dedication to be good at in taking redsides, bull, cutts and, soon, steelhead and salmon, which are being reintroduced to the Metolius.

My hat is off to CalTrout. Bravo!

Everyone loves what you guys are usually up too. This kind of clever work and coverage! Keep up the fantastic works guys I’ve added you guys to my personal blogroll.