This originally appeared in the Spring 2018 edition of the Current

Salmon recovery in the Mid-Klamath Basin

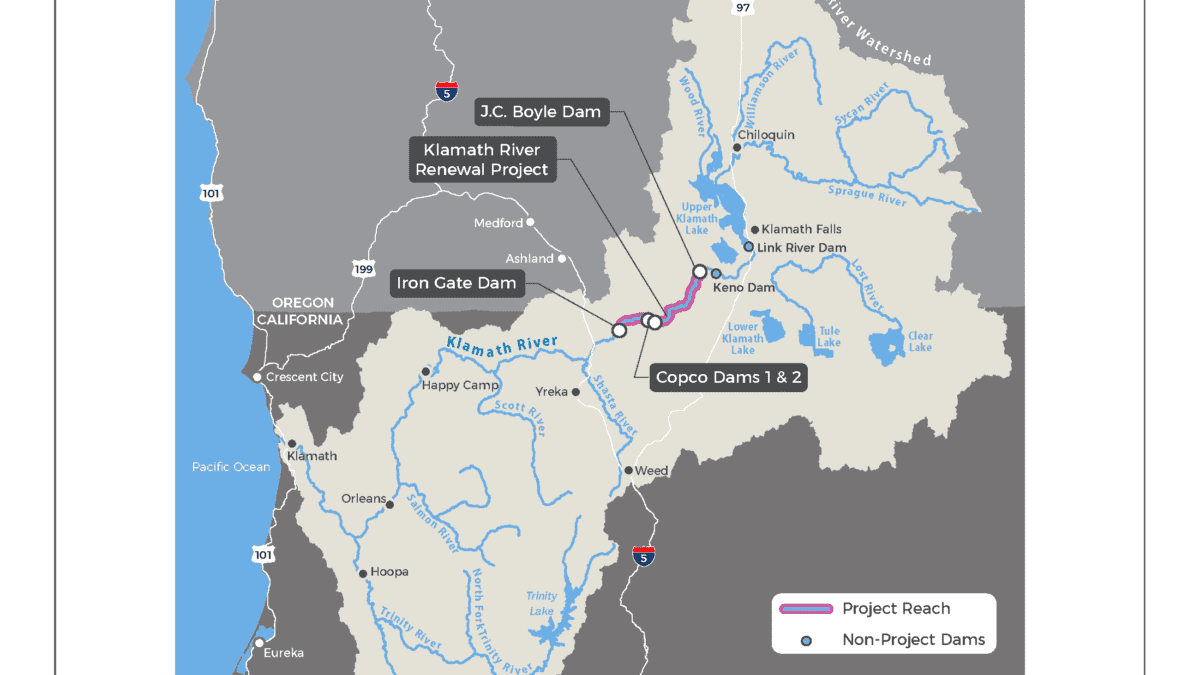

As CalTrout looks forward at our landscape-scale strategic objectives for the next three years, Klamath Dam removal jumps out as one of the most promising salmon recovery opportunities in the history of our organization. Hyped as the largest dam removal project in the world, we find it hard not to get excited about the prospect of spring-run Chinook reaching the headwaters of the Sprague, Williamson, and Wood rivers for the first time in over 100 years.

The Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC)—the herculean nonprofit organization tasked with dam removal—shows on their website an ambitious timeline of sub-accomplishments needed to meet the goal of dam removal within the 2020-2021 window. CalTrout and our conservation partners have an appointed seat on the KRRC Board and are active in ensuring that the many steps towards removal stay on schedule. Click here to see KRRC’s dam removal timeline.

Most notably, over the next two years, the KRRC will have to work through the highly bureaucratic Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) process for License Transfer and Surrender. On a parallel path, KRRC will have to navigate the California and Oregon 401 Water Quality Certification Process and the FERC National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process. If the FERC and permitting process go well, KRRC will then turn their attention towards the solicitation and contracting challenge of hiring a qualified design and build construction firm. All this must be accomplished while simultaneously carrying out a massive education and outreach strategy to communicate effectively with dozens of special interest groups, government agencies, tribes, farmers, and private landowners.

Key nurseries for the Klamath Basin

As the KRRC prepares to meet these challenges head on, CalTrout is also ready to act. Dam removal will improve water quality and reduce fish disease throughout the mainstem Klamath River. With the lethal impact of these factors diminished, the Shasta and Scott tributaries can resume their historic role as key nurseries in the Klamath Basin for threatened coho and fall-run Chinook. As Dr. Peter Moyle noted, “This is one of the most productive river systems in the entire Klamath Basin, so if you improve conditions in the Shasta River for salmon and steelhead, you’re improving conditions for in the entire Klamath Basin.” Historically, the Shasta River produced more than 50% of all the returning adult Chinook in the entire Klamath Basin while the Scott River consistently generates one of the largest returns of wild northern California coast coho salmon in the state (NRC, 2004). When the Klamath Dams come down, the Shasta and Scott need to be ready.

Significant work remains, however, to prepare these basins for an influx of healthy returning adult salmon. Over the next three years, CalTrout is uniquely positioned to carry out large-scale restoration projects on private lands. Both the Shasta and the Scott Rivers suffer from water diversions to support agriculture, which degrades flow and water quality at critical times of the year for salmon. Diversion dams also restrict access to important spawning and rearing habitat. To directly address these issues, CalTrout engages water users—primarily multi-generational family farmers—by offering incentives for voluntary cooperation in restoring habitat for salmon. In 2017, CalTrout partnered with the Hart Ranch on the Little Shasta River to secure a multimillion dollar grant to completely retool the ranch’s irrigation infrastructure. By replacing leaky pipes and valves, improving water management, and being more efficient with agricultural operations, the Hart Ranch was then able to use California water code 1707 to dedicate meaningful water savings back to the stream for salmon. Not only did the Hart Ranch upgrade their infrastructure and improve their water efficiency but in doing so they drastically reduced their exposure to environmental litigation under the Endangered Species Act.

CalTrout is currently working with other landowners in the Shasta and Scott rivers to replicate this voluntary, incentive-based model. By bringing partners to the table voluntarily, farmers often take great pride in the stewardship of natural resources, better water management, and the recovery of threatened or endangered species. As Blair Hart is fond of saying, “We know how to grow cows. We don’t know how to grow fish. But we’re going to learn.” CalTrout facilitates this learning process by offering the technical and financial assistance landowners need to understand how their agricultural operations affect aquatic ecosystems and the complex life history strategies of salmon and steelhead.

CalTrout also develops partnerships with leading academic institutions like the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences to ensure that all our work and restoration strategies remain grounded in science. Finally, CalTrout taps into tools and policies like voluntary Safe Harbor Agreements and California Water Code Section 1707 to find legal solutions for landowners that want to support salmon recovery efforts but might be discouraged by regulatory roadblocks or fear of litigation.

As Klamath Dam removal moves closer and closer to reality, CalTrout continues to work as part of the KRRC and with a broad coalition of long-time partners to ensure that the FERC license transfer and surrender goes smoothly at the federal level. In rural Siskiyou County, CalTrout continues to work towards restoring two of the most important salmon producing tributaries in the entire Klamath Basin. Combined, these strategies ensure that when the Klamath Dams do finally come down, fish will return to healthy waters for a better California.