How we're working to save them:

- Reconnect rivers with oxbows, side channels, and floodplains (e.g., Sutter and Yolo bypasses), and set back levees to increase valuable feeding habitat.

- Clip the adipose fin on all hatchery Chinook salmon and implant coded wire tags in a fraction of fish to improve research and management.

- End trucking of hatchery Chinook to the San Francisco Estuary to limit straying to non-natal watersheds and reduce hybridization.

- Relocate hatcheries in estuaries to minimize competition and gene flow between hatchery and wild stocks, and allowing hatchery fish to be harvested while freeing wild populations to recover and adapt to local conditions.

- Close hatcheries where adverse impacts outweigh benefits.

Where to find Central Valley Fall-Run Chinook Salmon:

Central Valley Fall-Run Chinook Salmon Distribution

Central Valley fall-run Chinook salmon historically spawned in all major Central Valley rivers from the upper Sacramento, McCloud, and Pit rivers (Siskiyou County) in the north to the Kings River (King County) in the south. Today, they are restricted to a small fraction of their historical habitat by dams in every major river in the Central Valley. Passage into the mainstem San Joaquin River, above the confluence with the Merced River, is intentionally blocked at Hills Ferry by a CDFW-operated weir. On the Sacramento River, Keswick Dam near the town of Redding blocks upstream migration.

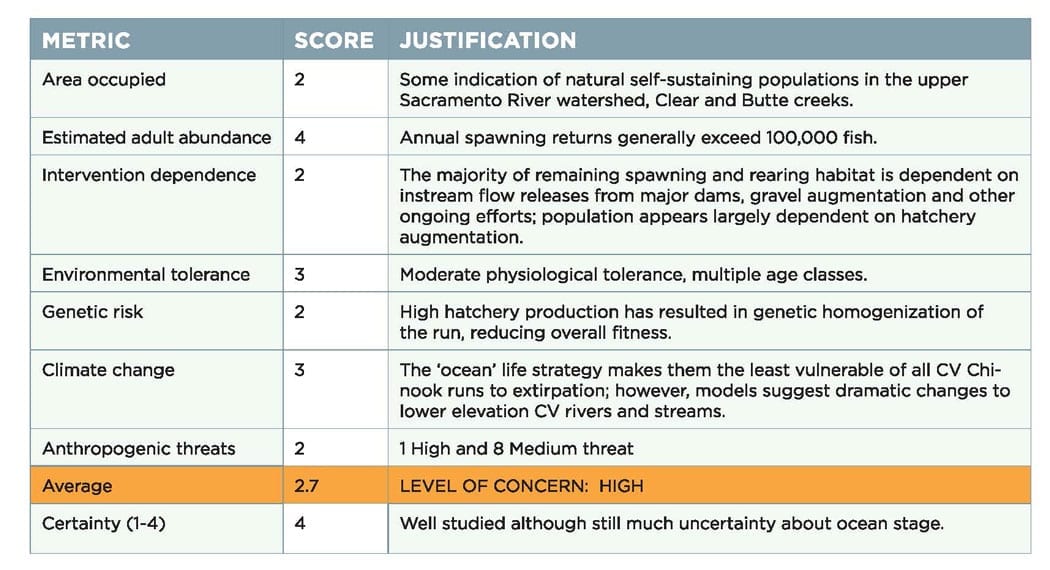

How they Central Valley Fall-Run Chinook Salmon Scored:

Characteristics

Central Valley fall-run Chinook are generally smaller than late fall-run Chinook, typically measuring 45-60 cm (18-24 in.) in length, and weighing 9-10 kg (20-22 lbs.). Fall-run Chinook salmon make up the largest run in the Central Valley today, and once supported robust commercial and recreational fisheries in the Pacific Ocean and fresh water. Due to low adult returns, the fishery has either been closed or restricted every year since 2008.

Abundance

The historical abundance of fall-run Chinook salmon is difficult to estimate because populations declined significantly before good records were kept. Best estimates suggest that as many as one million fall-run Chinook salmon once returned to spawn in the Central Valley each year. Gold mining, dam construction, and commercial fishery impacts caused stocks to plummet by the 1940s. Annual runs have averaged around 150,000 fish per year over the past decade. Most returning adult fall-run Chinook salmon are from hatcheries today, with only a few streams in the northern portion of Sacramento Valley sustaining wild runs.

Habitat & Behavior

Adult CV fall-run Chinook salmon return to fresh water in late summer and early fall, and spawn relatively quickly after reaching spawning grounds in mainstem rivers. Spawning peaks from October-November, but can continue through December and into January if stream conditions allow. Juveniles emerge from December through March, and spend up to seven months feeding before migrating downstream in spring. Fall-run juveniles are younger and smaller than other Chinook juveniles during their downstream migrations. Most juveniles enter salt water in late spring and early summer, when upwelling currents provide abundant food. Immature fall-run Chinook typically spend between two to five years in the Pacific Ocean from Point Sur (Monterey County) to Point Arena (Mendocino County) before returning to fresh water as adults to spawn.

Genetics

Hatchery operations that increase straying of fish to various rivers have produced a genetically homogenous population of fall-run Chinook salmon, and wild and hatchery fish are now indistinguishable from each other. This hatchery- mediated loss of genetic diversity is a major threat to the continued existence of Chinook salmon in California, which rely on genetic and life history differentiation to adapt to changing environmental conditions over time. Decades of interbreeding between fall and spring-run Chinook salmon has produced hybrid fish that return to the Feather River in spring, but are nearly genetically identical to fall-run Chinook. Despite differences in genetics, life histories, and run-timing, NMFS groups fall-run and late fall-run Chinook salmon into a single “special concern” ESU.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.