How we're working to save them:

- Restore spring-run to the San Joaquin River watershed, where they can exploit the snowpack predicted to persist in the high southern Sierra.

- Protect and enhance cold water habitat in Deer, Mill, and Butte creeks through water acquisition or forbearance, conjunctive use of groundwater wells, water use efficiency improvements, and shifting land use practices and management.

- Remove passage barriers to spring-run Chinook salmon throughout their range, especially in Battle Creek and the Yuba River.

- Restore floodplains that serve as important nursery and feeding habitat for all juvenile Central Valley salmonids.

- Amend hatchery practices to eliminate interactions between Feather River Fish Hatchery Chinook and wild populations.

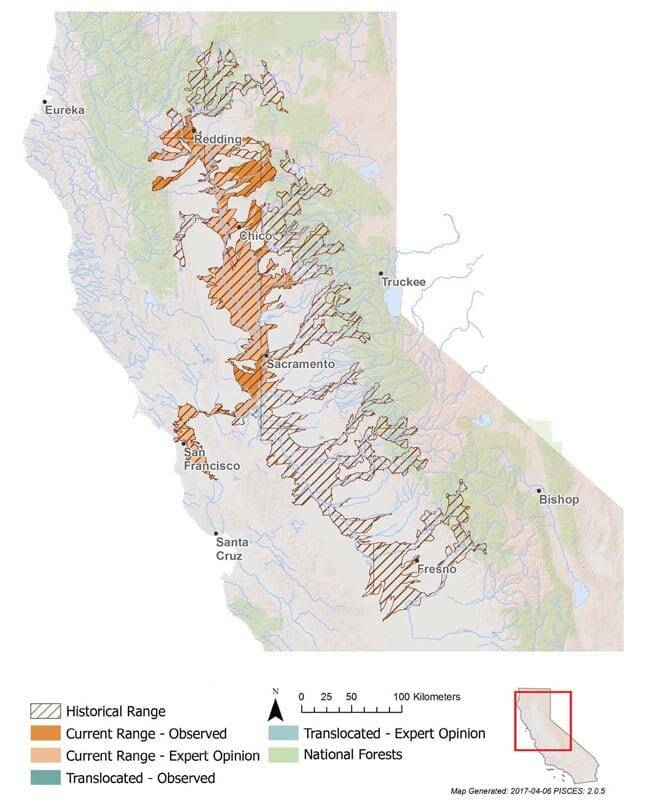

Where to find Central Valley Spring-Run Chinook Salmon:

Central Valley Spring-Run Chinook Salmon Distribution

Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon historically ranged throughout all major snowmelt tributaries of both the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, including the Pit River (Modoc County) and the headwaters of the San Joaquin River in the south (Fresno County). Today, only the mainstem Sacramento River and Butte (Butte County), Mill, and Deer creeks (Tehama County) maintain wild spring-run Chinook. In most years, some adults return to Antelope, Big Chico, Little Chico, Beegum, Battle, and Clear creeks, but these populations are not considered self-sustaining. Recent surveys have documented very few spring-run Chinook in the Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced rivers.

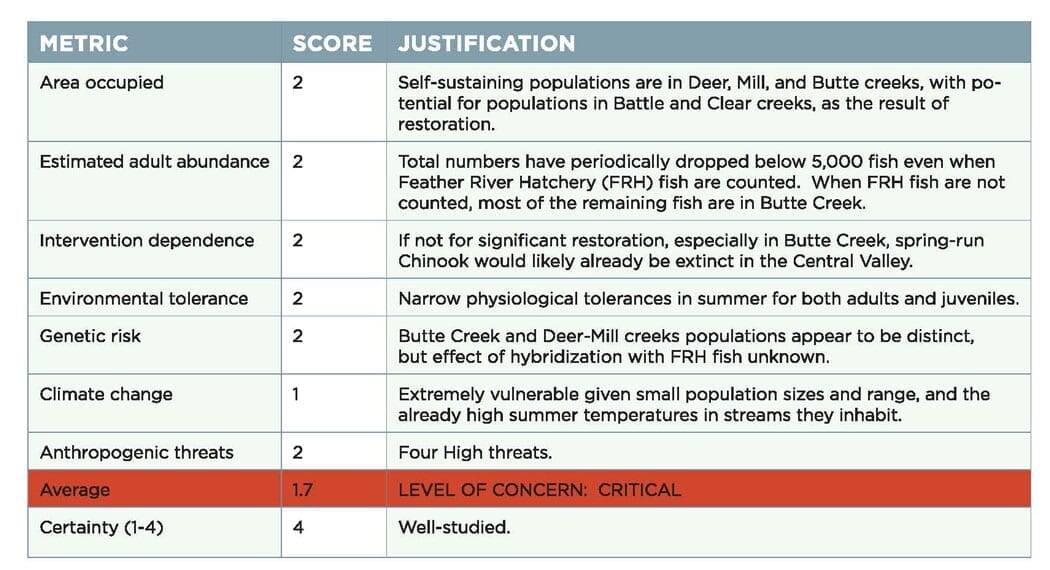

How they Central Valley Spring-Run Chinook Salmon Scored:

Characteristics

All California Chinook salmon are similar in appearance, with some slight differences in size, shape, and coloration. Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon are separated by their run timing, spawning areas, and late maturation in fresh water.

Abundance

19th-century spring-run Chinook salmon were once as abundant as fall-run Chinook in the Central Valley, numbering approximately one million returning adults per year. Over the past forty years, annual abundance has varied considerably, from highs around 30,000 fish to lows of about 3,000 fish. Since 2012, population estimates have plummeted.

Habitat & Behavior

Spring-run Chinook salmon migrate upstream during high runoff events starting in January or February. High flows, especially from snowmelt, allow adults to access higher elevation, smaller tributaries in April through June that are generally inaccessible to salmon at other times of the year. Adults seek out deep, cool pools in tributary streams less than 21°C (70°F) where these big fish hold over the summer before spawning in the fall. They prefer pools with plenty of cover, such as rock ledges, bubble curtains, and woody debris. Most spring-run Chinook adults in the Central Valley are four years old and average 78.5cm (31 in.). Juvenile spring-run Chinook spend varying amounts of time in freshwater before migrating to sea: 1) a matter of weeks after hatching, 2) a few months after hatching, or 3) an entire year or more in fresh water.

Genetics

The delayed maturation strategy in spring-run salmon arose as a single evolutionary event in a Chinook population and spread throughout the species’ range, primarily through straying of fish to other watersheds. There are only two distinct self-sustaining populations of Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon: one in Deer and Mill creeks and one in Butte Creek.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.