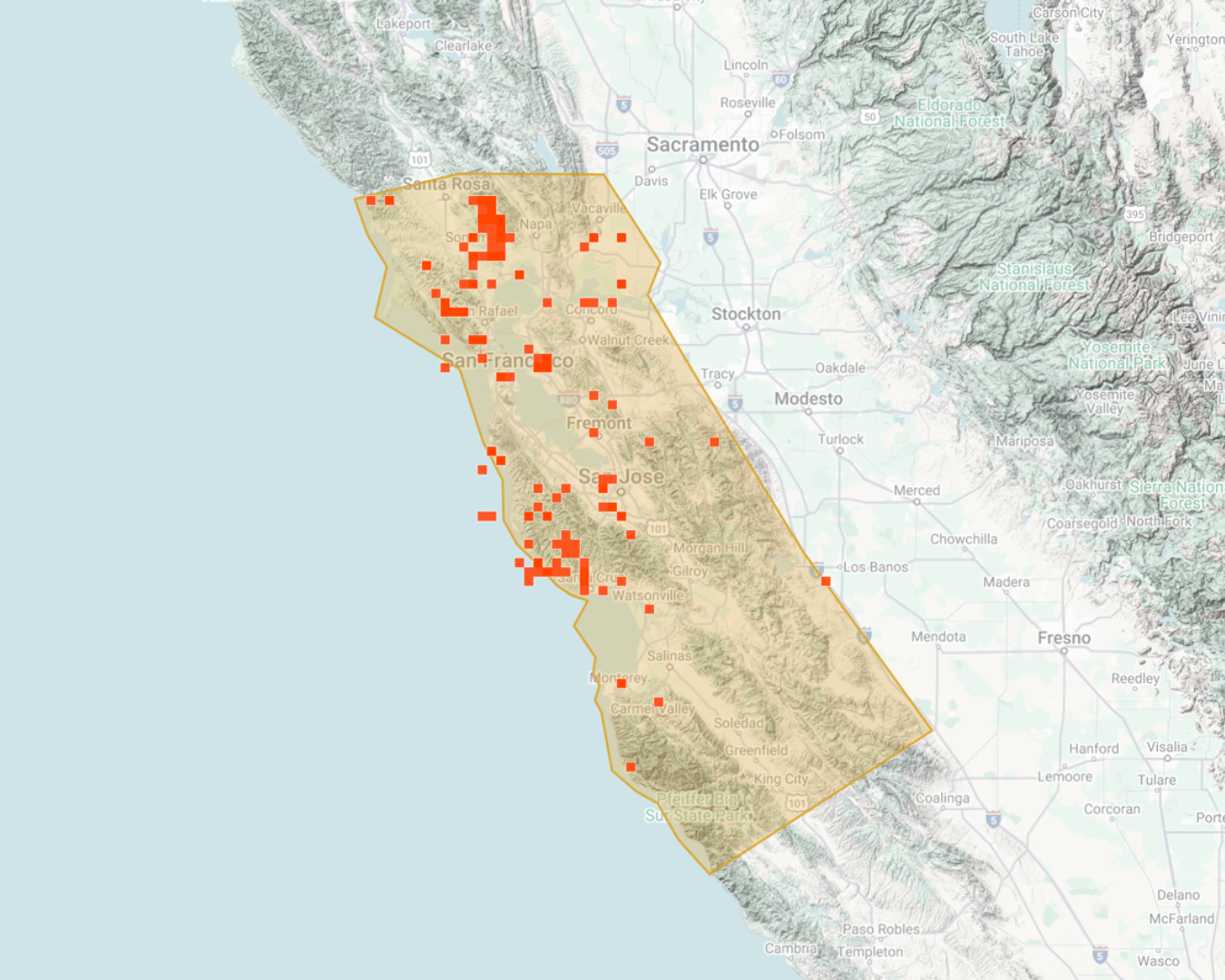

Thank you to everyone who participated in our iNaturalist campaign this past winter to document salmon and steelhead in Bay Area rivers and streams! The submitted photos and observations help us build a more complete picture of how fish migrate through and use Bay Area watersheds to inform restoration and management efforts. We loved following along with your observations as you explored your local rivers and streams, finding fish, alive and deceased!

By the Numbers:

- 323 observations

- 154 observers

- 70 species identifiers

- 42 different watersheds, San Francisco Bay, and the Pacific Ocean

- 11 counties

- 3 species (coho salmon - 47, Chinook salmon - 203, rainbow trout- 47)

How does this information support our restoration efforts?

At CalTrout, we focus our efforts where we can make the biggest impact. These decisions are driven by science and your observations helped us build out our Bay Area data pool. Understanding where fish are showing up, especially in places we might not have realized, reveals where we should build out more comprehensive monitoring programs and explore future restoration opportunities. This is especially true for California’s critically endangered coho salmon.

Your observations also show whether fish are able to pass potential obstructions to their traditional migratory routes, which includes fish ladders, culverts, and road crossings, among others. They can help us understand the geographic extent of fishes’ ranges, if new habitat is being used, or if historical habitats are being recolonized. This can help us keep tabs on how fish populations, such as threatened Central California Coast steelhead, are reacting to changing conditions on the landscape, such as drought, wildfire, and atmospheric rivers.

Lastly, fish observations in newly accessible areas directly after a restoration project such as barrier removal helps us determine the efficacy of the work. Proof of success allows us to secure additional funding and investments for our restoration efforts – a necessity to scale our work and impact.

Understanding how your observations coincide with migration patterns

Your fish observations occurred primarily during December 2025, which is the beginning of California’s winter and wet season. The environmental changes that coincide cue salmon to begin their migration upstream to spawn. Out of the 324 total number of observations, 204 were of Chinook salmon, 47 of coho salmon, and 47 of rainbow trout.

Many of you captured photos of actively spawning salmon. By spring, baby salmon have successfully hatched, reared in our cool streams, and finally migrated out to the San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean before the arrival of our hot, dry summers. One, two, or possibly even three years from now, some of those fish hatched this winter will return as adults from the ocean to spawn and complete their life cycle.

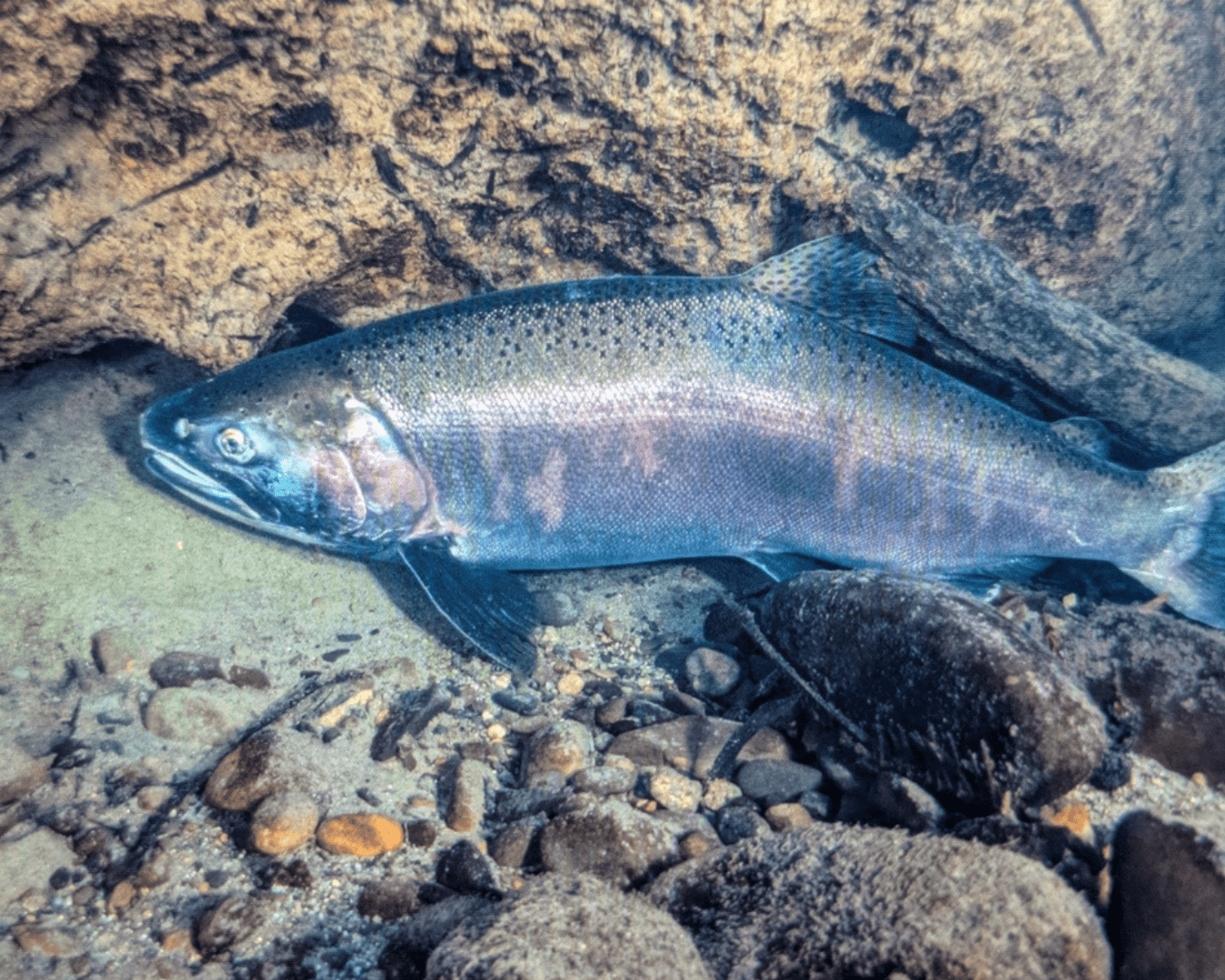

Steelhead tend to wait a little while for streamflows to recede before they make their move. They are also relatively harder to document because they tend to be more secretive, moving primarily when streamflow is high and the water is turbid, or under the cover of darkness. If you’re lucky enough to observe one, they can be found in Bay Area streams through March, and almost all surviving steelhead have made their way back out to the ocean by May or June.

Steelhead eggs in the gravel hatch in late spring or early summer and typically rear in our streams, estuaries, or lagoons for 1-2 years before growing to sizes that can sustain them on their journey to the Pacific Ocean. Steelhead are much less rigid than salmon in this pattern, however. They have significant diversity in their rearing habits, outmigration timing, and years spent at sea before spawning.

Check out some of the amazing photos you all submitted, below!

Diving into Your Data:

You may have heard that salmon return to where they were born to spawn and complete their life cycle. Most do, but some portion of the population every year wanders to other watersheds, sometimes near, and sometimes far. This is natural and experts refer to it as straying. This mixing of fish from different watersheds helps maintain genetic diversity and support populations in streams that are dependent upon immigration of fish from nearby watersheds.

The coho salmon and steelhead observed by community scientists in this effort are part of the greater Central California Coast populations of coho and steelhead, respectively, and regularly move between watersheds from the Russian River south to Santa Cruz County.

Water connects us all and that is demonstrated through these straying behaviors. These fish depend on connected, healthy streams along the coast to complete their life cycles. The Chinook salmon observed in this effort are likely, but not always, Central Valley fish that were raised in a hatchery and released into the Pacific or San Francisco Bay as juveniles that took advantage of winter storms to enter Bay Area streams to spawn. This is especially true in very wet years, when Chinook can access just about any creek with a few inches of depth that connect to the ocean or the bay.

There are still some Central California Coast Chinook around that are native to our area in Bay Area streams, but they are very rare. Rainbow trout, which spend their lives entirely in freshwater and never migrate to the ocean, still inhabit many Bay Area watersheds above barriers such as dams and reservoirs. These wild fish retain their genetic integrity despite historical stocking of hatchery rainbow trout into these watersheds.

Your observations highlight the interconnectedness of our communities – human and wildlife. These remarkable species – coho salmon, Chinook salmon, and steelhead/rainbow trout - exist right here in the Bay Area’s backyards where we live, work, and play. They are key indicators of healthy watersheds, a necessity for thriving, sustainable societies.

This community science program reveals that we all have a role to play. By observing, stewarding, and protecting the watersheds and fish in our backyards, we can together create a more resilient California.

Dive into some of CalTrout’s restoration work to protect and restore Bay Area native fish here, and tune into an exciting fish passage project on Alameda Creek that kicked off this summer!