Scaling Floodplain Conservation and Salmon Recovery in California’s Central Valley

By The Jacobs (Montgomery and Katz)

Fish Food is Made on Floodplains

Like all living things, fish need to eat. In large river valleys the fish food needed to support abundant fish populations is primarily made in wetlands. But in the Sacramento Valley, like in most other large river valleys in the developed world, the former floodplain wetlands that once supplied that food energy have been drained and cut off from leveed river channels, primarily for conversion to agriculture. Loss of more than 95% of the wetlands formerly connected to Central Valley streams has resulted in depriving the river ecosystems of the energy needed to make native fish biomass. The building of thousands of miles of levees in the Central Valley has resulted in massive population declines of California’s native fish. Put simply, levees starve salmon.

In California, fish are not only an important part of our natural legacy and cultural heritage, but also endangered populations are the legal proxy by which the health of the state’s rivers are judged. Meaning that the legal mechanisms for regulating the supply of water into California’s economy are significantly influenced by the relative health of specific fish populations. This means that in short, endangered fish populations also threaten the secure supply of one critical natural resource fueling the world’s 4th largest economy (4.1 trillion-dollar GDP) – water.

But our science is clear: endangered fish are not an inevitable result of California’s development. Instead, their impending extinction is a direct result of water and farm infrastructure built before we understood how California river valleys functioned and how fish used them. Now, our research demonstrates that by integrating a 21st century understanding of ecological process into the management of our rivers, California can have both its fish and its farms. However, we will only be able to recover fish populations and secure our water supplies for both farms and cities if we restore the interactions between rivers and the landscapes through which they flow on a landscape-scale. Because the Central Valley is almost entirely privately owned, the math of salmon recovery will rely on building trust and partnerships with those that own and operate the Valley’s working lands.

Getting the Fish to the Food

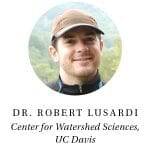

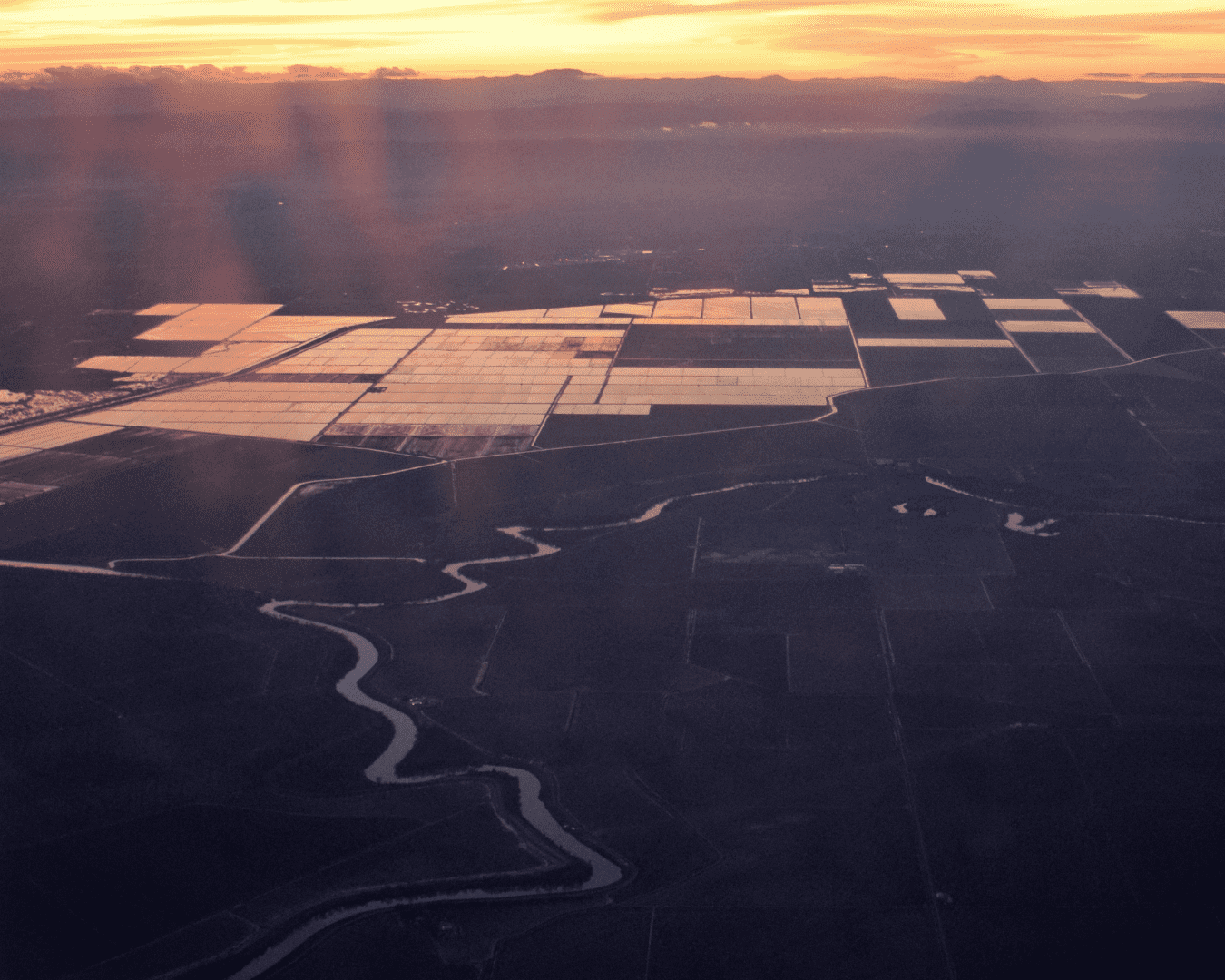

“Swim through wetlands” is the best way to get juvenile salmonids access to food-rich floodplain wetlands. The concept can be applied anywhere that floodwaters full of fish can spread out and slow down over low-lying wetlands adjacent to stream channels. The catch, of course, is that most formerly hydrologically connected wetlands have been cut off from stream channels by levees. With European settlement of the Valley in the mid-1800s, levees began to be constructed to protect agricultural and urban development. Today, less than 5% of wetlands remain connected to river channels and thus accessible to fish during high water events. Fortunately, within the Sacramento Valley exists a corridor of landscape-scale flood protection projects designed to direct flood waters away from critical urban and agricultural areas.

By diverting high flows onto specifically managed floodways these “bypasses” alleviate flood threat to Sacramento and other cities. The bypasses are extensively farmed during summer but can flood multiple times during the winter/spring wet season.

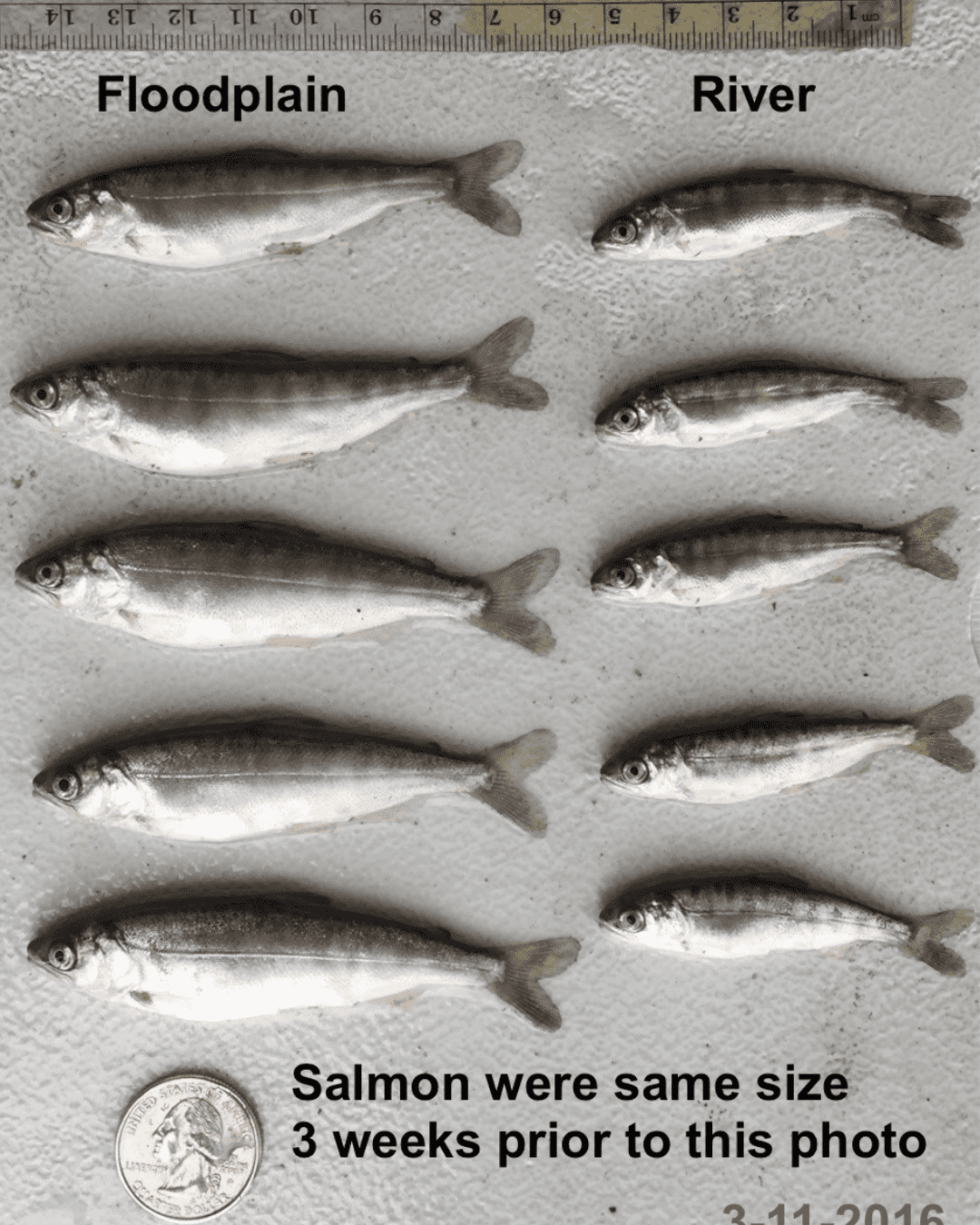

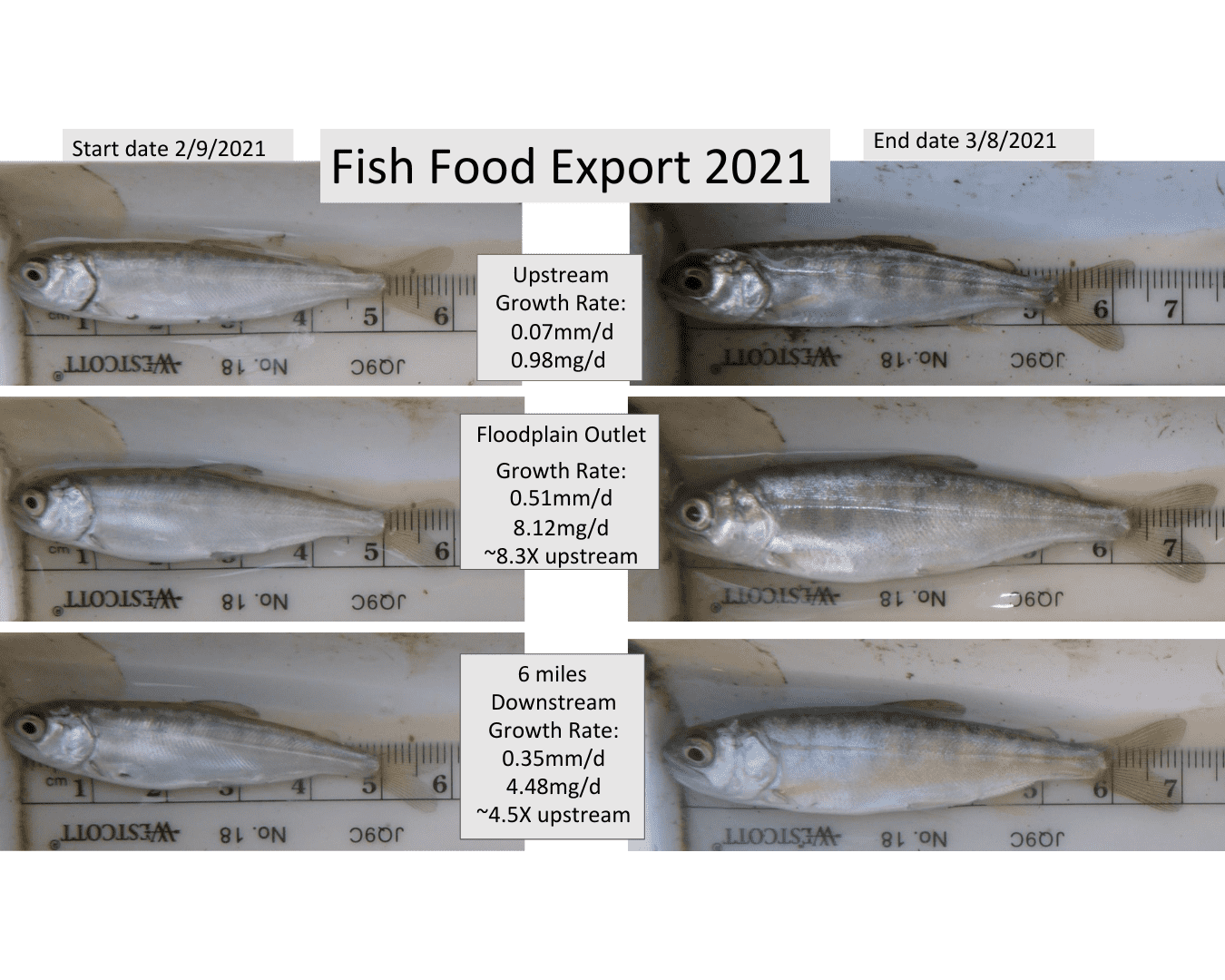

The “Nigiri Concept” is the name of CalTrout’s collaborative effort between farmers and conservationists to help restore salmon populations by reconnecting young salmon with winter-flooded bypass fields (which are primarily in rice agriculture). These “surrogate wetlands” mimic the floodplain rearing habitat used historically by young salmon which has been largely eliminated by the development of the Central Valley. Inundating bypass fields in winter when crops are not grown allows us to create high-quality habitat for fish, birds, and wildlife while keeping farms in active ag production in summer. These managed ag wetlands can produce up to 15,000% more invertebrate biomass than the leveed river channel can, and fish can grow up to 12x faster on these activated floodplains.

CalTrout has forged deep and trusting partnerships with fish and bird conservation organizations, fishing interests, farmers, water suppliers, flood protection, and environmental regulation agencies to facilitate fish conservation actions within the bypass system. This effort focuses on increasing the frequency and duration of floodplain inundation events during winter to maximize the benefits accrued by fish rearing on the roughly 90,000 wetland acres within the bypasses. While this is a truly huge step towards salmon recovery, it is insufficient by itself. To truly rebuild the historical power and abundance of Central Valley floodplains requires also reactivating the productivity of the floodplain acreage that remains inaccessible to fish on the other side of levees.

While the vast majority of formerly connected wetlands in the Central Valley have been either drained or cut off by levees, there are at least 500,000 acres of floodplain habitat in the Central Valley on the “protected” side of large flood protection levees. While fish can’t swim to inundated “dry side” floodplains, these lands can still contribute to recovering fish stocks. CalTrout’s Fish Food program brings these floodplains to the fish. Or more accurately, the program delivers the fish food made on inundated dry-side floodplains to fish stuck within leveed and food-starved rivers. The Fish Food Program works with farmers and wetland managers to flood parcels of land (~85% rice agriculture, ~15% wetland habitat) to create the wetland conditions that produce abundant zooplankton and aquatic invertebrates. After the water is teeming with this protein-rich fish food, the fields are drained back to a fish bearing channel (e.g., Sacramento River, Feather River, Butte Creek, etc.) where they can be eaten by young salmon.

Same Land, More Benefit

The program's results were innovative and exciting, but we had some questions. Could a field be reflooded after growing a ton (literally) of bugs and draining them back to the river? Could the same field be flooded and drained multiple times a season? We knew it worked once, but would abundant fish food be produced in subsequent flood cycles? And even if it worked, would farm and wetland managers be willing to adopt greater operational duty? Beginning in 2021 we set out to get those answers.

Our monitoring data from the last several seasons clearly demonstrates that fish grow as fast during subsequent drainage cycles as they had in the first. And, because we were paying per flood and drain cycle, we found most landowners were willing to flood and drain multiple times. In 2021 we enrolled 8,775 acres in the program and 2,164 of them completed two cycles. In addition to increasing the overall volume of fish food delivered to the river, enacting multiple cycles also spread out the food benefits over time - meaning more fish could access it throughout their outmigration season. With that, we were off to the races and have been building the program year by year.

In 2022, we developed the online infrastructure for public, open enrollment into the Fish Food program in order to broaden landowner engagement. The California Rice Commission's partnership in this effort was transformative. Their conservation branch, the California Ricelands Waterbird Foundation, has a successful track record of facilitating waterfowl and shorebird conservation programs on winter-flooded rice fields. Hosting the Fish Food application on their website facilitated immediate broad access to the rice community from a trusted partner.

Results and Impact: Three Years of Proven Success

With the help of a technical advisory committee consisting of experts from UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, Delta Science Council, Point Blue Conservation, The Nature Conservancy, California Rice Commission, and Ducks Unlimited, we developed a description of the Fish Food practice and a simple application form on which farmers provide information about where they are located, to where and along what route their water drains, how many acres and how many cycles they are willing to enroll, when they can have drainage events occur, and what that will cost. We then created a scoring rubric which ranks applications according to which will be most impactful based on a suite of criteria. The criteria are simple: total acreage (more is better), number of cycles (more is better), timing of cycles (some nuance here based on what salmon runs are present in which watersheds at which time, e.g. timing for winter-run Chinook is prioritized for fields that drain to the Sacramento River, but the same timing score is not relevant in the Feather River where there are only fall and spring-run Chinook), distance from field to fish bearing channel (shorter is better), and cost (cheaper is better). We also coordinate with other winter conservation programs for waterfowl and shorebirds to ensure that growers are not getting paid by multiple programs for the same action. A grower can enroll in a bird program and the Fish Food program at the same time (or sequentially), but they can’t get paid twice for the same actions.

We have grown the number of flood acre cycles (a single acre flooded and drained) every year since implementing this reverse auction program in 2022. Since that time funding for the program (approximately 2 million dollars a year) has come directly from Congress via a federal ear mark with the support of the Floodplain Forward Coalition. Each year has seen an increase in total bids submitted, as well as an increase in flood/drain cycles per acre and a decrease in cost per cycle. (See Table 1.) The data suggests that interest in the program from the floodplain community is continuing to grow as we cultivate a culture of more intensive management of winter flooding for the benefit of fish and aquatic ecosystems. It is also gratifying to see the market-driven bid process increasing the impact of our limited conservation dollars. We are getting more environmental benefit on the same amount of land for less money! That’s a cool triple bottom line!

Table1: Fish Food program bid summary stats

| Year | Budget | Bids | Acres selected | Cycles selected | Cycles per acre selected | Cost per cycle selected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 1,990,000 | 29 | 29,000 | 43,000 | 1.48 | $46.28 |

| 2024 | 2,089,079 | 42 | 27,400 | 54,800 | 2.00 | $38.12 |

| 2025 | 2,107,556 | 64 | 25,100 | 59,600 | 2.37 | $35.36 |

Funding Challenges and Future Vision

Where do we go from here? Unfortunately, the funding we have been relying on for these past three years is no longer available. At the time of writing this (June 2025), we do not have funding for a Fish Food program for Water Year 2026. We have developed a novel and increasingly more efficient aquatic conservation easement program with proven benefits to endangered and declining fish populations, local communities, and California’s economy - and yet we have no money to implement it. Our task now is to find dedicated, long-term funding. The standard model for this type of environmental incentive program is the Natural Resource Conservation Service Environmental Quality Incentives (NRCS EQIP) program, funded by the Farm Bill through the US Department of Agriculture. While we are currently applying to the NRCS in their Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP), federal funding for the program and staffing to implement are anything but secure.

The Fish Food program demonstrates the potential to create landscape-scale benefits for fish, like those that have led to the recovery of migratory water birds. Last year, on approximately 25,000 acres we achieved nearly 60,00 flood and drain cycles of high quality food delivered to juvenile fish in the Sacramento Valley during their rearing and outmigration life stage. To generate the food web energy that will help recover salmon stocks, we believe we need to enroll 100,000 acre cycles a year at minimum, preferably 150,000 cycles. With increased efficiencies coming from scale, we think we could do that for around $4-6M dollars a year. That may seem like a lot for an annual conservation investment, but compared to the downside risks to California’s economy resulting from a failing aquatic ecosystem and subsequent water restrictions, that money would be only a drop in the proverbial bucket.

How Can YOU Help?

At CalTrout, we know that effective restoration is grounded in scientific research – yet it's often underfunded and overlooked. Private donations help us expand our body of knowledge where data gaps might exist and scale our proven successes – AND they help us leverage larger public investments. If you’re interested in getting involved, you can join our volunteer community, attend an upcoming event, or make a gift to CalTrout. Together, we will continue to partner across industries to recover fish populations, boost local economies, and create more resilient communities.