CalTrout Questions Loss of Protected Rivers Caused By Raising Shasta Dam

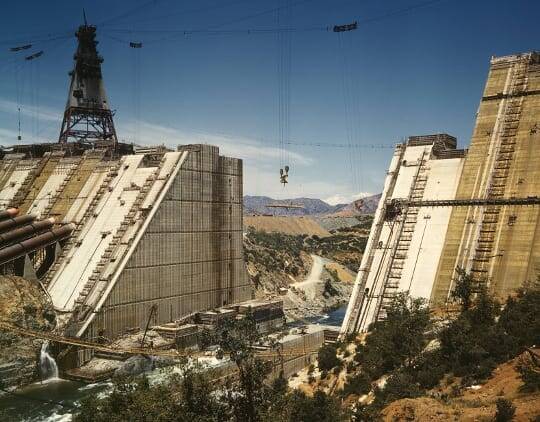

The Shasta Dam prior to completion.

Raising Shasta Dam, flooding McCloud & Upper Sacramento Rivers contradicts state Wild and Scenic Rivers Act

When the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) released their Draft Feasibility Report (DFR) and the Preliminary Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Shasta Dam raising project, it concluded that raising Shasta Dam 18.5 feet (flooding stretches of the McCloud and Upper Sacramento Rivers in the process) was the preferred alternative.

The BOR determined that raising the dam would benefit salmon and steelhead downstream and provide more water for irrigation in the Central Valley. CalTrout is concerned about the potential raising of Shasta Dam for many reasons, including:

- The McCloud River has given enough. Two dams block access to the McCloud’s anadromous fish, divert over 80% of its flow and flood miles of habitat.

- The McCloud River is protected under the state Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, and rolling back these protections sets a dangerous legal precedent.

- Benefits of dam raising to Central Valley salmon populations needs to be addressed comprehensively with other Central Valley salmon and steelhead projects. For example, the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Draft Central Valley Recovery Plan gives no mention of the Shasta Dam raise project.

- The Upper Sacramento River — one of California’s most-popular with fishermen and other recreational users — also stands to lose up to two miles of flowing water.

The McCloud: A Remarkable River

By the late 1800’s, fisheries experts and anglers from around the world looked to the 77 mile-long McCloud River for its hard-fighting steelhead, the colorful redband trout, its abundant salmon runs, the only California occurrence of the aggressive bull trout, and the unique winter-run Chinook salmon (found nowhere else in the world).

Today, all the species listed above are gone save the Redband, which clings precariously to a few small feeder creeks in the upper watershed. It’s ironic that the McCloud’s hardy trout and salmon stocks were transplanted all around the globe, so they now survive in many other places, but not here.

A River Dammed

How did we lose so many of the McCloud’s fish? First, we dammed it, separated it from the sea, flooded its lower 14 miles, and extirpated its salmon and steelhead.

Then another dam was constructed in a middle stretch, which turned six more miles of it into a lake, diverted over 80% of the base flow into the neighboring Pit River, and extirpated its bull trout.

Simply put, we have cut the river off from the sea, eliminated five of its six species of native trout and salmon, inundated nearly half of the free flowing river, and siphoned off most of the water from the half that remains.

The McCloud, it seems, has already suffered enough.

State Protection

What remains of the McCloud is an extraordinary resource. The 25 miles of river between McCloud Dam and Shasta Dam is one of the most popular fly fishing destinations in the world. The rainbow trout are the seed stock that was sent to the far reaches of the globe, earning them the title of ‘trout of the world’.

In 1989 the legislature declared the McCloud “one of the finest wild trout fisheries in the state” and further went on to pass special protective legislation (*see note at end of article) that declared “maintaining the McCloud River in its free-flowing condition to protect its fishery is the highest and most beneficial use of the waters of the McCloud River.”

Not only are new trout rivers not being created, but the McCloud River enjoys special legislative protection due to its value as a unique recreational resource .

The BOR acknowledges the McCloud’s special status in their “Major Topics of Interest” section, but distressingly offers almost no mention of the loss of up to two miles of the Upper Sacramento River, and dances around discussions of the effects flooding would have on the McCloud River:

Specific information is lacking concerning the river reach that could periodically be inundated if Shasta Dam and Shasta Lake were enlarged because the lands along this part of the river are privately owned and access for biological and other surveys has been limited; therefore, general information concerning the lower McCloud River as a whole is provided for some resource areas.

Given the owners of that “private stretch” of the McCloud River are none other than Westlands Irrigation District — who bought the property specifically to eliminate one barrier to dam raising — it’s hard to imagine what the barriers to discovery are.

Dam Raise Cost & Proposed Benefits

The Bureau of Reclamation study identifies a cost of $1.2 billion to raise Shasta Dam. Who benefits from this raise and who should pay?

The BoR claims that $655 million dollars of the project should be attributed to salmon recovery due to a larger cold water pool in Lake Shasta.

If salmon recovery is really the goal, we question whether spending $600 million to raise Shasta Dam is the best use of funds. The National Marine Fisheries Service Draft Recovery Plan for Central Valley salmon identifies a number of actions (including reintroducing salmon to the Upper Sac and McCloud above Shasta Dam). But there is no mention of the Shasta Dam raise as an identified recovery action.

How can two federal agencies be so uncoordinated about salmon recovery needs? One wants to spend over a half-billion dollars on recovery and the other (the one actually in charge of the fish) does not even identify the project at all.

The BOR suggests that 61% of the “benefits” of a higher Shasta Dam would go to fisheries (typically salmon), so taxpayers would presumably be on the hook for approximately $655 million of the cost.

The Redding Record-Searchlight correctly suggests that handing taxpayers a majority of the bill is a “shell game” and that irrigators — where the majority of the newly stored water is headed — won’t end up paying their fair share:

But the feasibility study released this week that concludes enlarging the dam and reservoir is both possible and cost-effective makes a curious argument. A bigger dam isn’t just coincidentally good for the fish. Rather, they are the major beneficiary — with more than 61 percent of the bigger dam’s benefits attributed to fish and wildlife enhancement, as opposed to irrigators, urban water users, and hydroelectric customers.

That means 61 percent of the projects costs — roughly $655 million, according to the estimates released this week — are not “reimbursable.” That is, they couldn’t be added to water users’ bills. Instead, presumably, the taxpayers at large would be on the hook.

Sorry, but this smacks of a shell game. The people who stand to gain from a deeper Lake Shasta are the owners of major agribusinesses with iffy junior water rights prone to cutbacks in dry years — among them the San Joaquin Valley’s Westlands Water District. They benefit both from the extra water itself, and from the steps to improve fisheries, which ultimately aim to remediate the damage done by the Central Valley Project and avert further potential water cutbacks related to endangered-species protection.

The Redding-Searchlight has sniffed out an ironic truth: the Central Valley’s anadromous fisheries need rescuing largely because of the Central Valley Water Project, which cut off access to the cold waters of the Upper Sacramento, Pit and McCloud Rivers.

Now the project’s negative effects are being used to justify an expensive addition to the project — and the loss of even more of California’s Blue-Ribbon Rivers?

What Do The Scientists Say?

As the scientists at the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences California Water Blog noted, if we’re asking taxpayers to cough up $655 million to benefit fish, then it’s fair to ask if fish wouldn’t better benefit from spending that $655 million some other way:

New major water projects are increasingly justified based on recovering fish and environmental benefits lost through construction of previous projects. Yet we are not seriously studying what would be the best investment portfolio for fish and the environment. We are still trying to justify individual projects rather than trying to find the best portfolio of activities to accomplish objectives, particularly environmental objectives. This approach is backwards, and ineffective.

Independent single-facility studies of improvements to a complex system are expensive and time-consuming, and distract us from addressing greater system-wide problems. If we continue to study this complex system incrementally, money and time will be spent without substantial improvements or strategic direction.

And as further noted in the California Water blog, the increased water capacity in the lake will result in very expensive water, while added water deliveries aren’t significant on a state-wide scale:

- The study found that the most economical expansion was about 14% (634,000 acre-ft), costing $1.1 billion dollars, roughly $1,700 per acre-ft of storage capacity. This would expand statewide surface storage capacity by 1.5%, although water storage capacity is not equal to water deliveries.

- This expansion produces an additional 76,000 acre-ft of firm yield (dry year deliveries). This is less than 0.2% of agricultural and urban water use in California. (Modern water engineers will wonder why the antiquated firm yield is still the main water supply indicator.) Average annual deliveries increase by only 63,000 acre-ft. Other traditional benefits (hydropower, recreation, flood reduction) were small.

We remain unconvinced of any increased recreational opportunity accruing to the project should more flat water be created; blue ribbon trout streams are rare, and new ones are not being created. Meanwhile, Shasta Lake already offers more than 30,000 acres of surface area and 365 miles of shoreline, so the added stillwater recreational opportunities are negligible.

Cultural Impacts

And while our objections focus on resources, there is a cultural cost to raising Shasta Dam; it would submerge 43 of the remaining Winnemem Wintu’s sacred sites under the lake’s waters.

Keep in mind that most of the tribal sites were lost when the lake was originally flooded, and most of what’s left would ultimately disappear.

CalTrout’s Concerns

This is a complex issue — one that resists bullet points — but as a conservation group, we’re concerned about this project on several levels.

1) The loss of irreplaceable river habitat and recreational uses on the McCloud and Upper Sacramento Rivers

The McCloud River and Upper Sacramento River are perhaps the two of the most-commonly fished of California’s blue-ribbon trout waters, and the impacts to those who depend on them for recreational or economic purposes are largely ignored in the BoR assessment.

2) Circumvention of the McCloud River’s specially protected status

The McCloud River enjoys special protection (see note below), and raising Shasta Dam violates that protection. These protections should not be subject to revocation whenever they become inconvenient.

3) Fishery benefits of the Shasta Dam raise need to addressed in a comprehensive way

Is raising the dam a priority for Central Valley salmon and steelhead restoration? The National Marine Fisheries Service doesn’t think so — it’s not even mentioned in recovery plans. Central Valley salmon recovery is a complex matter and cannot be viewed solely through the lens of raising Shasta Dam.

Raising Shasta Dam will come at the expense of the Upper Sacramento and McCloud Rivers — the latter of which the California Legislature acknowledges as one of the most beautiful and valuable in the state.

While CalTrout remains committed to protecting and restoring Central Valley anadromous fisheries, raising Shasta Dam is an enormously expensive project (made even more expensive by the loss of chunks of the Upper Sacramento and McCloud Rivers — and the mitigations that would ensue), and the benefits simply don’t add up.

(*Note: A 1989 amendment to the California Wild and Scenic Rivers Act described the McCloud as “one of the finest wild trout fisheries in the state” and stated that “The continued management of river resources in their existing natural condition represents the best way to protect the unique fishery of the McCloud River” and that “maintaining the McCloud River in its freeflowing condition to protect its fishery is the highest and most beneficial use of the waters of the McCloud River.”)

3 Comments

It’s all about Jerry Brown’s push for water down south! If those 2 water tunnels get built, than Southern California developers and farmers are guaranteed water. In order to keep water heading down south they will have to raise dams up North. Jerry Brown is making a deal with developers and farmers which will gaurentee pushing water south even during drought years. State has hired bioligist that claim fishing will not be affected. Most these guys were unemployed and have sided with the state for a paycheck back in 2009. If this project goes through, no doubt this will stress most of Northern California waterways one way or another.

Lastbrown;

First let me say that I too am against the dam. However, the comments you make do nothing to promote factual exchanges. Your diaphanous attempt to tie Governor Brown to the biologists “most of these guys were unemployed and have sided with the state for a paycheck back in 2009”, is seemingly a misleading political commentary. Mr. Brown was not the Governor in 2009, and the biologist’s apparently have been employed for the past 3 to 4 years.

I wonder if a better use for the money needed to construct the dam and underground water tunnels, might not be instead used to construct a desalination plant.

fishinterest;

Yes, Your correct, Brown was not in office when this all started. Arnold Schwarzenegger had been pushing this measure for several years prior.