Science-based Solutions

CalTrout is established as a credible scientific leader on fish and water issues in California. Through its Science program, CalTrout improves its scientific foundation of applied conservation strategies while developing responses to statewide-big picture threats to native trout and salmon such as climate change, ongoing drought conditions, introduced and invasive species, and hatchery reform. The program enables CalTrout to provide scientific research, data collection, and analyses to inform adaptive management strategies and viable conservation alternatives aimed at restoring native trout and steelhead throughout their historical range.

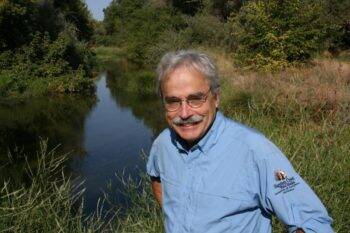

Two positions, created in 2014 between California Trout and UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, work toward these science goals: The Peter B. Moyle California Trout Endowed Chair in Coldwater Fishes and the CalTrout-UC Davis Wild and Coldwater Fish Researcher, currently held by Rob Lusardi, Ph.D., one of the authors of the SOS II: Fish in Hot Water report.

I have a long history working with salmon and trout. My first publication on California’s amazing fish fauna was a short note on juvenile Chinook salmon in the Kings River in 1970, where I captured them on a field trip with a fish biology class. Only later did I discover salmon had spawned in the river after an absence of 28 years! The resilience of salmon, steelhead, and other native fishes has continued to impress me ever since.

Unfortunately, my career has been spent documenting their decline in California, starting with the extirpation of Bull trout. But I have also long realized that California’s unique fishes, especially its salmonids, are worth fighting for. Not only are they resilient, but they are beautiful, with astonishingly diverse life histories and habitats. Saving these fishes means saving special waters: the cold streams that flow through redwoods, rivers in urban southern California, unique lakes such as Eagle Lake, and complex estuaries. But saving these fishes also means living with change. Even as human-induced changes on the landscape have continued to intensify, it is the resilience of salmon and trout that keeps them with us.

But this adaptability only takes them so far; their existence now depends on what we do. I am proud to say that I have been a member of California Trout almost since its beginning, when it was pretty much Dick May, the organization’s founder. From its inception, California Trout has been as much about keeping streams and lakes wild, as it has about fishing. That attitude still makes me happy to work with California Trout, even if it is to document the continued decline of our special fishes, as in this report. If knowledge is power, then this information should be critical in reversing the trend, with California Trout at the forefront of aquatic conservation.

This brings us to the present State of the Salmonids report. This second edition is a much improved version of the report that Josh Israel, Sabra Purdy, and I put together in 2008 for California Trout.

This report had its genesis in the 1976 and 2002 versions of my Inland Fishes of California1 and in the Fish Species of Special Concern in California2 reports, which teams from my laboratory generated for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The authors of this present report undertook the task of re-evaluating the status of California salmonids because:

- We really like these fishes;

- We wanted to provide more comprehensive information than was present in other sources, under one cover;

- We wanted to further develop and us a method for assessing the status of each species in quantitative manner that is repeatable and allows comparisons among species; and

- We wanted to discuss the many controversial ideas about how to improve management of California salmonids to reverse their downhill slide, and add some ideas of our own.

- We really like these fishes (!);

- We wanted to provide more comprehensive information than was present in other sources, under one cover;

- We wanted to further develop and us a method for assessing the status of each species in quantitative manner that is repeatable and allows comparisons among species; and

- We wanted to discuss the many controversial ideas about how to improve management of California salmonids to reverse their downhill slide, and add some ideas of our own.

Frankly, I also thought that only California Trout was likely to be bold enough to sponsor the task of comprehensive evaluation.

The gap between the 2008 and 2017 reports is 10 years,3 a very short period to detect change. But we felt that the time was ripe for it because the 2012-16 drought stressed virtually all salmonid populations in the state, a major test of their resilience.

We regarded the drought as harbinger of the effects of global warming/climate change. The 10-year period was also one in which much new information appeared on the salmonids, especially on species listed under the state and federal endangered species acts. As we began drafting the 2017 report, we realized that the new information and increasingly obvious impacts of climate change required us to rethink the metrics used in the 2008 report to evaluate status. In 2017, we added a new metric and improved the calculation of three others.

Unfortunately, these improvements meant we could not directly compare the status scores of each species from 2008 with those from 2017, as had been planned.

We were able, however, to compare the verbal judgments of status, based on the score ranges. The verbal ‘scores’ still revealed that California salmonids were markedly worse off than they were 10 years ago. While drought was certainly a major contributing factor, each species has its own story to tell of unique factors causing continued decline.

It is raining outside as I write this and as we finish a record wet-water year. We can only hope that our salmonid fishes will respond positively to this dramatic turn-around in flows in our rivers. But we do have to recognize that record drought followed by record precipitation is likely to characterize the future in California; global climate change is causing increased variability in the place that already has the most variable climate in the United States.

At the same time, I consider myself fortunate to live and work in a state that often exercises leadership in conservation. Therefore, what we Californians do to enhance the resilience of our native fishes is likely to set examples for the rest of the world.

This is a big responsibility, but I am happy to be part of making it happen with California Trout.

--------- I have a long history working with salmon and trout. My first publication on California’s amazing fish fauna was a short note on juvenile Chinook salmon in the Kings River in 1970, where I captured them on a field trip with a fish biology class. Only later did I discover salmon had spawned in the river after an absence of 28 years! The resilience of salmon, steelhead, and other native fishes has continued to impress me ever since. Unfortunately, my career has been spent documenting their decline in California, starting with the extirpation of Bull trout. But I have also long realized that California’s unique fishes, especially its salmonids, are worth fighting for. Not only are they resilient, but they are beautiful, with astonishingly diverse life histories and habitats. Saving these fishes means saving special waters: the cold streams that flow through redwoods, rivers in urban southern California, unique lakes such as Eagle Lake, and complex estuaries. But saving these fishes also means living with change. Even as human-induced changes on the landscape have continued to intensify, it is the resilience of salmon and trout that keeps them with us. But this adaptability only takes them so far; their existence now depends on what we do. I am proud to say that I have been a member of California Trout almost since its beginning, when it was pretty much Dick May, the organization’s founder. From its inception, California Trout has been as much about keeping streams and lakes wild, as it has about fishing. That attitude still makes me happy to work with California Trout, even if it is to document the continued decline of our special fishes, as in this report. If knowledge is power, then this information should be critical in reversing the trend, with California Trout at the forefront of aquatic conservation. [readmore] This brings us to the present State of the Salmonids report. This second edition is a much improved version of the report that Josh Israel, Sabra Purdy, and I put together in 2008 for California Trout. This report had its genesis in the 1976 and 2002 versions of my Inland Fishes of California1 and in the Fish Species of Special Concern in California2 reports, which teams from my laboratory generated for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The authors of this present report undertook the task of re-evaluating the status of California salmonids because:

I have a long history working with salmon and trout. My first publication on California’s amazing fish fauna was a short note on juvenile Chinook salmon in the Kings River in 1970, where I captured them on a field trip with a fish biology class. Only later did I discover salmon had spawned in the river after an absence of 28 years! The resilience of salmon, steelhead, and other native fishes has continued to impress me ever since. Unfortunately, my career has been spent documenting their decline in California, starting with the extirpation of Bull trout. But I have also long realized that California’s unique fishes, especially its salmonids, are worth fighting for. Not only are they resilient, but they are beautiful, with astonishingly diverse life histories and habitats. Saving these fishes means saving special waters: the cold streams that flow through redwoods, rivers in urban southern California, unique lakes such as Eagle Lake, and complex estuaries. But saving these fishes also means living with change. Even as human-induced changes on the landscape have continued to intensify, it is the resilience of salmon and trout that keeps them with us. But this adaptability only takes them so far; their existence now depends on what we do. I am proud to say that I have been a member of California Trout almost since its beginning, when it was pretty much Dick May, the organization’s founder. From its inception, California Trout has been as much about keeping streams and lakes wild, as it has about fishing. That attitude still makes me happy to work with California Trout, even if it is to document the continued decline of our special fishes, as in this report. If knowledge is power, then this information should be critical in reversing the trend, with California Trout at the forefront of aquatic conservation. [readmore] This brings us to the present State of the Salmonids report. This second edition is a much improved version of the report that Josh Israel, Sabra Purdy, and I put together in 2008 for California Trout. This report had its genesis in the 1976 and 2002 versions of my Inland Fishes of California1 and in the Fish Species of Special Concern in California2 reports, which teams from my laboratory generated for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The authors of this present report undertook the task of re-evaluating the status of California salmonids because:

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.