The Era of Dam Removal is Upon Us: CalTrout Talks About Taking Them Down

CalTrout Supports Dam Removal… Where It Makes Sense

One of the largest threats to trout, steelhead and salmon are dams. And California has plenty of them — more than 1,200 dams greater than 25 feet high.

These dams submerge rivers, block fish migration, and reduce or eliminate downstream water flows — the lifeblood of healthy rivers. In the Sierra Nevada alone, dams have flooded and blocked over 90% of the rivers that drain this majestic mountain range.

CalTrout is involved with many projects throughout the state to mitigate the impacts of dams, including providing fish passage, improving flows below dams to decrease water temperatures, and, in some cases, advocating for the removal of dams.

Outlived Their Usefulness

Many of the largest dams built in the west are between 50-100 years old and have outlived their usefulness for flood control or water supply — usually due to filling in with sediment. Many are now being evaluated and dam removal is a serious consideration.

When these dams were built our knowledge of how river systems worked was limited.

Consider the progress we’ve made in other areas such as science, technology and health. Fifty years ago we had yet to place a man on the moon, personal computers did not exist, and we did not fully understand the adverse effects of smoking.

Similarly, we did not fully understand river systems and could not begin to predict the impact dams would have on rivers systems and their inhabitants.

We now understand more about the true cost of damming rivers and for some, dam removal makes sense. Following are some examples of dam removal projects CalTrout has been involved with throughout California.

Which Dams Should Come Down?

On the Klamath River, CalTrout has worked with many stakeholders, including PacifiCorp (the dam owners), to remove four dams on the river. The aging dams produce relatively small amount of power and block over 400 miles of steelhead and salmon spawning habitat. PacifiCorp has determined the cost of removal is cheaper than upgrading the dams to meet mandated fish passage requirements such as fish ladders. As a result, a Settlement Agreement is being implemented now that will lead to dam removal in 2020.

In Southern California, CalTrout has advocated for the removal of Matilija Dam on the Ventura River. Completed in 1948, the dam has had two disastrous impacts. The Southern steelhead population, estimated at 5,000 fish in 1940, immediately collapsed starting with a massive fish kill in 1949. And, the dam trapped sediment thus starving local beaches and drawing the concerns of surfers and beachgoers.

Today, the dam is completely silted in and does nothing for flood control or water supply. CalTrout has been active in developing removal plans that include the incremental notching of the dam to facilitate the safe and steady transport of sediment downstream.

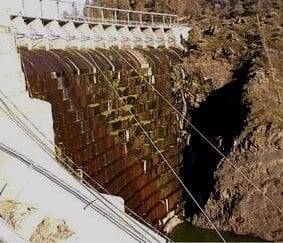

San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River has been rendered useless due to sedimentation. The 106 foot high structure blocks access to over 25 miles of threatened steelhead habitat and has major safety deficiencies. In 2008, a Carmel River reroute and dam removal project was initiated. Like most dam removal projects, what to do with the sediment is a primary issue. To address this, the Carmel River will be rerouted for a half mile into San Clemente Creek, allowing the abandoned stretch to act as a sediment storage area. Dam removal is being led by the state Coastal Conservancy and Cal Am (the owners of the dam). In 2011, CalTrout supported legislation to help fund this project.

Rindge Dam on Malibu Creek in Southern California is also being considered for removal. The 100 foot high dam was completed in 1924 and blocks access of Southern steelhead to the upper reaches of Malibu Creek. The dam has long been obsolete – filling in with sediment within a decade of being built. CalTrout has long advocated for the removal of Rindge Dam and this fall a report on the feasibility of dam removal will be released by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and others.

Recently, CalTrout and partners (American Rivers and the Beyond Searsville Dam Coalition) are urging Stanford University to assess the feasibility of fish passage and removal of Searsville Dam on the San Fancisquito Creek which flows through the Stanford campus.

For over a century, Stanford University’s antiquated Searsville Dam has impacted San Francisquito Creek watershed and the greater San Francisco Bay estuary. Built between 1890 and 1892, the 65’ tall x 275’ wide Searsville Dam has lost over 90% of its original water storage capacity as roughly 1.5 million cubic yards of sediment has filled in the reservoir. Searsville Dam does not provide potable water, flood control, or hydropower. CalTrout and partners are advocating for fish passage or dam removal at Searsville to allow steelhead to return to over 10 miles of habitat in the upper watershed.

Successful Dam Removal Projects

In recent years, there have been successful dam removal projects in California. Seltzer Dam on Clear Creek near Redding was taken down in 2000. At the time, this was one of the largest dam removal projects in the state. Last year, the process to remove five dams on Battle Creek began to open access to 48 miles of endangered salmon and steelhead habitat.

And this year in Washington state, two long-anticipated and ambitious dam removal projects are starting, underscoring that the age of dam removal is upon us.

In September, two dams on the Elwha River on the Olympic Peninsula are being removed. One of these—Glines Canyon Dam—is 210’ tall and will be the tallest dam ever removed.

Condit Dam on the White Salmon River is also being removed this year. Condit Dam is owned by PacifiCorp, the same owners of the Klamath Dams. Both of these long anticipated dam removal efforts help set the precedent for removing dams that no longer serve their intended purpose.

CalTrout will continue its work assessing the possibility for dam removal where it makes sense. Not only have many dams become useless and hazardous, but they are one of the primary impacts on our native fish. Dam removal can be one of the most efficient and effective ways to bolster salmon and steelhead stocks by providing access to historic spawning and rearing areas. CalTrout will continue to advocate for this.

2 Comments

Bravo Cal Trout. Well said statement. I grew up standing in San Francisquito Creek and now live in Oregon. There is some really good potential for salmon to once again live in this forgotten fishery. Before the dam was built people would come from all around to fish the fall/ winter salmon and steelhead there. Stanford has a golf course which is probably the biggest obsticle for them, as the dam provides water for it. Frankly it’s been frustrating trying to deal with them.

Cliff

Thanks for taking the time to comment here. The Searsville Dam issue is an interesting one for a whole bunch of reasons, one of them being Stanford’s involvement. I’m sure they’re susceptible to pressures a corporation wouldn’t experience.