“Everything started pointing towards Alameda Creek,” he explained.

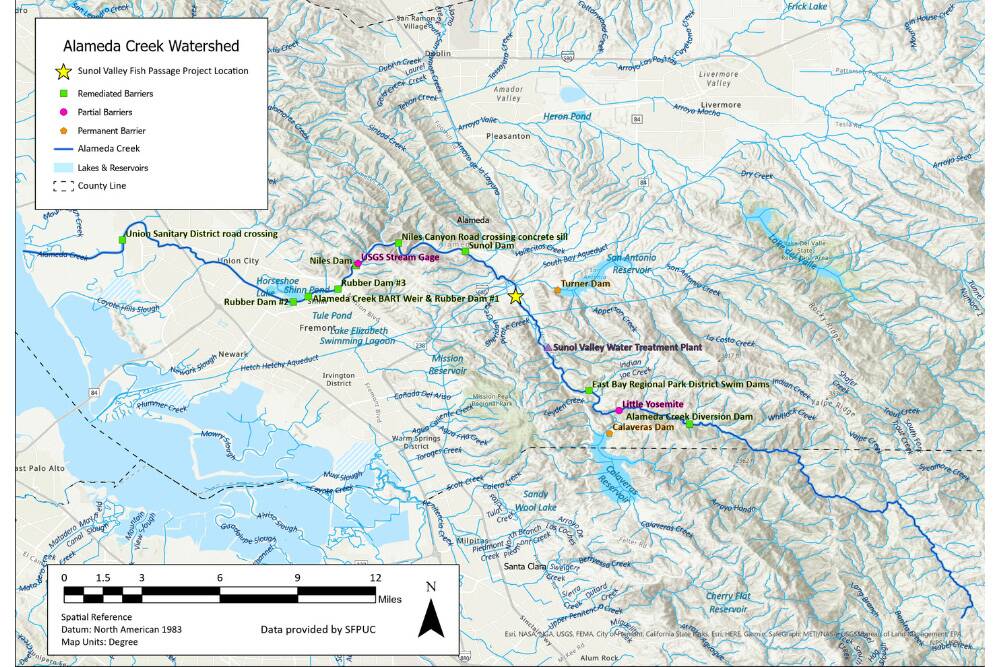

In 1997, Miller founded the Alameda Creek Alliance (ACA). In the past twenty years, the organization has pushed and helped partner agencies to complete 16 fish passage projects in the Alameda Creek watershed. In 2022, newly constructed fish ladders enabled Chinook salmon and steelhead to migrate through the lower creek into Niles Canyon and access parts of the upper Alameda Creek watershed for the first time in over fifty years. Soon, these fish will be able to consistently swim even further upstream. In 2023, California Trout was asked to lead a barrier removal project in Sunol Valley to open more than 20 miles of stream in the upper watershed to Chinook salmon and steelhead, remediating the last unnatural barrier on mainstem Alameda Creek.

The current remaining barrier is created by a major gas pipeline in Sunol Valley upstream of the Interstate 680 overpass. Owned by PG&E, the pipeline is covered in a protective layer of concrete, known as an erosion control mat, which protrudes up into the creek. This makes the creek impassable to fish during most stream flows. This past winter, there was plenty of water in the creek, but as California’s cycle of drought and deluge continues, resolving this last barrier to fish passage will ensure fish access upstream regardless of species, life stage or size, and if it’s a wet or dry year.

As the project lead, CalTrout will coordinate all project partners for permitting and grant funding applications. CalTrout will then lead the implementation effort, community outreach, and post-project monitoring. “This is the next upstream barrier for fish and we’re ready to tackle it,” said Claire Buchanan, CalTrout Bay Area Region Senior Project Manager. “We’re only able to address this barrier today after decades of effort by different partners and so many individuals continuing to push for a free-flowing Alameda Creek.”

PG&E’s gas pipeline in Sunol Valley protrudes up into the creek making it impassable to fish during most stream flows. Credit: PG&E

“I want the fish back”

Alameda Creek is the largest local tributary to the San Francisco Bay and historically produced large numbers of Chinook salmon, lamprey, and steelhead in the South Bay. Over the past century, the watershed experienced intense urbanization including the construction of three major dams and reservoirs. Until recently, the entire watershed was inaccessible to anadromous fish (besides Pacific lamprey which were able to sucker their way over some barriers). Despite there being no easy path into the watershed, adult steelhead were still showing up at the downstream barrier. “We put all these barriers in their way, and yet they are still trying to come back. It’s amazing and inspiring to witness their determination,” Miller said. “The Alameda Creek Alliance is really focused on building a constituency for these fish and for the creek.”

Lampreys in the Bay Area

Fun Fact: Alameda Creek is one of the few remaining watersheds in the Bay Area that supports Pacific lamprey, western brook lamprey, and at least historically supported western river lamprey!“Lampreys are an important part of the native fish assemblage in our streams and provide ecosystem services that support salmon. However, lampreys are not commonly visible as they spend much of their time buried in the substrate or moving at night,” said Damon Goodman, CalTrout Mt. Shasta-Klamath Regional Director. Goodman is a fish biologist by training and has devoted much of his life’s work to studying and contributing to restoration efforts across the state for lamprey.

The ACA aims to bring salmon and steelhead back to Alameda Creek and to protect and restore the largest local watershed in San Francisco Bay. With a staff of just two part-time employees, much of the ACA’s work is getting water and land management agencies, with more capacity and more financial resources, to care about this creek and its aquatic denizens, and to implement large-scale fish passage and habitat restoration projects.

In the early days, that meant bombarding the Alameda County Water District’s mailboxes with brightly colored postcards signed by water district customers proclaiming, “I want the fish back”. “Every week I would slip a few more in the mail,” Miller said.

Eventually, the stacks of postcards, combined with countless conversations with reporters, community members, and agency members, worked. In 1999, the Alameda Creek Fisheries Restoration Workgroup formed to bring together water and land management agencies, regulatory agencies, the ACA, local fly-fishing groups, and nonprofits. Finally, all the necessary players were in the same room. The workgroup cooperatively started to address fish passage in the watershed from funding to permitting to implementation. Together, the group has implemented fish passage projects, including removing dams and constructing fish ladders, that remediated 17 former fish passage barriers throughout the watershed. Most of these efforts were voluntarily undertaken by workgroup members.

"We put all these barriers in their way, and yet they are still trying to come back."

JEFF MILLER

“This part of the creek has resident trout, endangered frogs, and the potential to support something really special in a rejuvenated steelhead run,” Miller said. Soon, that potential will be realized.

Alameda Creek Watershed Map

The Last Remaining Barrier

In 2022 and 2023, former barriers at the BART weir and inflatable bladder dams in Fremont, 8-10 miles upstream of where Alameda Creek enters the Bay, were made passable for fish due to newly constructed fish ladders by the Alameda County Water District. This incredible opportunity for salmonids to migrate throughout the Alameda Creek watershed was the product of decades of hard work to improve fish passage by a myriad of partners in the Alameda Creek Fisheries Work Group.

CalTrout staff have engaged in the Fisheries Restoration Workgroup since 2019. In 2022, CalTrout staff assisted local partners to train volunteers to conduct fish spawning surveys along Alameda Creek. Today, CalTrout staff are continuing involvement in the watershed, with Buchanan at the helm leading the Sunol Valley Fish Passage Project.

To address this fish passage barrier, PG&E’s gas pipeline will be lowered approximately 20 feet beneath the creek bed, so it no longer protrudes above the creek. The channel restoration design plans are being developed by McBain Associates Applied River Sciences, a crucial project partner that CalTrout has collaborated with for many years across the state. The pipeline lowering plans are being developed by PG&E.

"“The upper Alameda Creek watershed is a really special place. It’s so close to the Bay Area but it feels very rural."

KATRINA HARRISON

“The upper Alameda Creek watershed is a really special place,” Harrison said. “It’s so close to the Bay Area but it feels very rural. I’m excited about this project providing the opportunity for people to see salmon in a wilder environment yet so close to Silicon Valley.”

PG&E will bury the pipeline deeper into the channel, remove the no longer necessary erosion control mat, and CalTrout’s contractor, Hanford ARC, will oversee the regrading and revegetation portion of the project. McBain Associates has an existing contract with PG&E to carry the project through 90% design. With support from McBain staff and Jeff Miller at the ACA, CalTrout staff are actively working to secure funding for 100% design, implementation and post-implementation monitoring.

Lower BART weir fish ladder. Credit: Alameda Creek Alliance

Alameda Creek upstream of the PG&E pipeline in Sunol Regional Wilderness. Credit: Claire Buchanan

A Corridor of Challenge…and Opportunity

Sunol Valley is a major utility and infrastructure corridor for the Bay Area. Freeways, gas pipelines, water lines, power lines, two aqueducts, and a railroad all cut through the valley. Much of the Bay Area’s water supply travels through Sunol Valley from Hetch Hetchy reservoir in the Sierra Nevada mountains. San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) owns and operates a network of water purveying infrastructure to ensure reliable water supplies and streamflow releases from their reservoirs to support ecological health. There are also active gravel quarries throughout the valley, including one located on the current project site, operated by DeSilva Gates Aggregates. Implementing a restoration project amongst all this infrastructure will certainly present challenges, and SFPUC and DeSilva Gates Aggregates are crucial project partners.Beyond the infrastructural challenges, new instream flows were implemented by the SFPUC beginning in January 2019, and have changed Alameda Creek’s channel morphology and vegetation. “It’s kind of like the changes that occurred when the streams entering Mono Lake were re-watered,” explained Scott McBain, McBain Associates founder and owner. “When it’s a dry wash, and then you put water back in, and you continue to re-water the channel in perpetuity, the channel morphology changes. The responses of plants, animals, and sediment transport all change too.”

Designing a restoration project with so many rapidly changing variables will be a challenge, but it’s one that McBain Associates staff are excited to tackle. “There are not very many places in the Bay Area where you have the ability to restore access to many, many, many square miles of good anadromous fish habitat,” McBain said. “This project is the last piece of the puzzle and a way to leave a legacy for the next generation.”

If all goes according to plan, project implementation could begin as early as summer 2025. “When this project is complete, fish will have unimpeded access into the highest quality habitat remaining in the watershed in and upstream of Sunol Regional Park,” Buchanan said.

"There are not very many places in the Bay Area where you have the ability to restore access to many, many, many square miles of good anadromous fish habitat. This project is the last piece of the puzzle.”

SCOTT MCBAIN

Will Ware, CalTrout Bay Area Project Coordinator, leads a training session for volunteers to monitor salmonids in Alameda Creek.

Following the Fish

Over 20 years after ACA founder Jeff Miller went looking for a way to help the local fish populations, San Mateo County resident Max Mader was searching for the same thing. He would start college the next year, and before leaving California for school, he wanted to find a way to get involved with his local watersheds. As an active fisherman, Mader was familiar with Alameda Creek and its importance for fish populations. When CalTrout advertised a fish monitoring volunteer opportunity with the ACA in 2022, Mader jumped at the chance.Between lower Alameda Creek where the new fish ladders were constructed and Sunol, no entities were actively monitoring fish populations yet in this newly-accessible habitat. During the fall and winter of 2022/2023, CalTrout supported the ACA in recruiting and training volunteers to fill this critical data gap. In these well-attended trainings, volunteers including Mader came together from all over the Bay Area to learn. Jeff Miller and ACA volunteers, CalTrout staff, Claire Buchanan and Will Ware, East Bay Regional Parks District staff, and others discussed with volunteers the history of the watershed, salmonids in San Francisco Bay, and how to use an app on their phones to document their findings. Mader’s favorite part about volunteering was attending the first training and information session.

“Everyone came together to learn about what we would be doing, and there were so many people from all ages and experiences,” he said. “From retired senior anglers who grew up fishing these same waters when the salmon runs would fill the riverbanks, to young environmentalists wanting to make a difference in their community and environment, it was very cool to hear everyone’s stories.”

“These fish have traveled all the way from the ocean and ended up in your backyard! It’s remarkable to think about it let alone to watch it happen.”

CLAIRE BUCHANAN

“This summer, I think 95% of my days were spent with a pole in my hand,” Mader said. “Besides being an active fisherman, I am also a conservationist. I understand how precious of a resource water is in California and how, without it, many things would not be the same.”