CalTrout Gets its Feet Wet

Creating a Model for Wild Trout Management

By Dick Galland, CalTrout Board Member and former owner of Clearwater House on Hat Creek

Hat Creek

Hat Creek rises clear and cold in Lassen Volcanic National Park and runs north through the Hat Creek Valley to meet the Pit River at Lake Britton. The lower three miles, below Hat Creek Powerhouse Two, form the renowned spring creek waters that have challenged anglers for over 50 years with abundant insect hatches and highly selective trout. Today, this hallowed ground is now officially designated Wild Trout Water, although that's a CalTrout story for another day.

This story starts with the genesis of CalTrout a half century ago, with a group of activist anglers who saw the need for an innovative approach to protecting California’s free-flowing waters and the wild fish within. Hat Creek is, in essence, the birthplace of California Trout - where passion became purpose, where ideas transformed into action, and where a new approach to wild water conservation irrevocably shaped the way we protect California’s wild resources – for the past fifty years, and forever.

A Radical Notion

CalTrout began as a group of enthusiastic anglers who met casually at a fly shop in San Francisco, often over lunch, to tell fish stories and lament the decline of quality fishing in the state. Dissatisfied with the accepted practice of stocking hatchery fish to supplement declining wild trout populations, these men believed that it might be possible to manage a fishery for wild fish and create a higher quality angling experience. This seems an obvious approach today–solving the problem by addressing the cause–but in the 1960s, this idea was entirely radical.

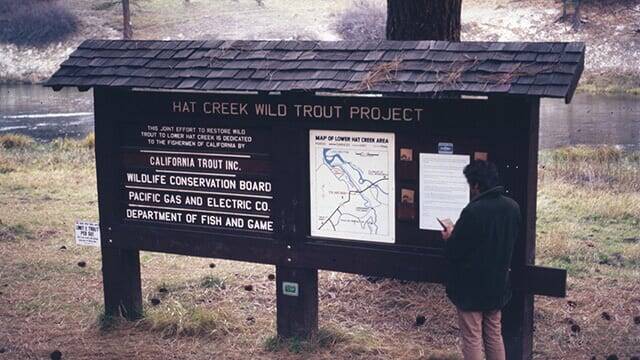

The Hat Creek Demonstration Project

“It was a demonstration project because we wanted to prove to the public, and to the powers that be in the Department of Fish and Game and the Fish and Game Commission, you could manage fish on a natural basis.”

- Richard May, CalTrout founding director

In 1968–three years before the organization would be officially organized–CalTrout’s founding members chose Hat Creek as their first demonstration project. Their goal was to restore the stream’s dwindling trout population by removing the Sacramento suckers and other non-game fish, which had overwhelmed the stream. Partnering with the Department of Fish and Game; Pacific Gas and Electric, the landowner; the Wildlife Conservation Board; and the National Fish and Wildlife Service, the team built a fish barrier on Hat just above the confluence with Lake Britton to keep rough fish out. Then the native rainbow and browns were shocked out and put in hatchery ponds for safe keeping. The stream was poisoned and over over six tons of suckers and squawfish were hauled away by volunteers in waders with big nets. Finally the stream was restocked with wild Pit River rainbow trout and wild browns from Trinity River. Special regulations limited the take to allow the trout population to grow and prosper.

A Wild Success

The wild trout population didn’t just prosper – it practically exploded! By the early 1970s, Hat Creek’s reputation as a wild trout fishery had spread across California. The 3 miles of trophy water represented some of the most remarkable fishing anywhere, with over 5,000 fish per mile and 16 fishable insect hatches across the season. Each year during the 1970s, nearly 10,000 fish were caught - and released (another radical notion at the time).

In barely more than a decade, Hat Creek was transformed from an unproductive stretch of water into one of the most renowned fisheries in the west. In 1971, flushed with their success, these activist anglers incorporated themselves as California Trout. The Hat Creek Demonstration Project paved the way for the concept of wild trout management in California and validated the efforts of these early California Trout activists.

That validation continues to affect how we approach all of our restoration and conservation efforts today. Not just with wild trout management, but across all initiatives. Whether we’re restoring high Sierra meadows, studying floodplain food sources, or supporting vulnerable estuary ecosystems, our work is guided by the knowledge that resilience comes from working with and supporting our natural systems.

In It for the Long Haul

In the 1980s, plumes of gray sand began to appear in the flats below the Powerhouse 2 Riffle. As the sand moved downstream, it buried plants and filled in the deeper parts of the creek above Carbon Flats, destroying habitat. The fish were pushed downstream, spawning declined, and along with it, fishing success and satisfaction.

The original restoration in 1968 had proved the concept that an intact stream, carefully managed for wild trout, could provide a quality angling experience. This time around, the challenge was very different. Hat Creek was no longer intact. The sediment — over fifty thousand cubic yards of volcanic ash, enough material to bury a football field to the very top of the goalposts — came from the eruptions of Mount Lassen in 1915. That epic blast sent a hot slurry of ash, mud, and water flowing down the Hat Creek Valley, burying farms and killing fish. In the years since the eruptions, the valley has been in the long process of recovery. The spring flows of Hat Creek, Lost Creek, and Rising River have slowly reestablished their streambeds, moving the volcanic ash downstream to settle out in the slow, deep water in Cassel and in Baum Lake, upstream of the Wild Trout Area. This process was stable for many decades.

In the 1980s, all that began to change. Sinkholes and lava tubes under Baum Lake that had been slowly filling with sediment since the eruption were unexpectedly flushed out during construction work on the Baum Lake dam, immediately above Powerhouse 2. This material, hundreds of times greater than Hat’s moderate flows could move quickly, overwhelmed the flats, burying everything as it went. It covered plants and spawning areas, destroyed insect habitat, and displaced trout. The creek became shallower. The bottom became as featureless as a beach. The fish had less and less suitable feeding and holding water. Fish surveys in the 1990s counted fewer than 2,000 fish per mile. In 2011, the fish count found less than 1,000 fish per mile. The streambanks had been eroded by anglers and hikers. Hat Creek was clearly in decline, anglers stayed away, and the local economy suffered with it.

So CalTrout stepped in again, but this time we brought decades of experience and the breadth of vision that comes with that experience. Helicopters delivered large woody debris into the river to create habitat structure for bugs and fish, and accelerate the stream flows. Invasive noxious weeds were removed from the riverside meadows. More than 5,000 riparian trees and shrubs were planted to stabilize the meadows and streambanks. A pedestrian bridge was built to allow anglers and other visitors explore the entire area. The slow, inexorable flushing of the sediment downstream has created a dynamic new stream, with a renewed bug life and greatly expanded spawning and holding areas for trout.

Equally important, this latest effort on Hat Creek has included the restoration of the relationship of the Illmawi Band of the Pit River Tribe with these, their ancestral lands. The Illmawi had an interest in returning Hat Creek to a healthy fishery; for, as the number of anglers had declined, the Illmawi had become dismayed by the behavior of other visitors who came to drink and party and behave disrespectfully on these ancestral lands.

An Oregon-based organization that trains tribal youths to restore native lands, created the Hat Creek Youth Initiative to provide Pit River youths with jobs, training and mentorship with natural resource professionals. These young people restored the land, planted the trees and shrubs, and built the trails and fences that define the renewed wild trout project. Clearwater Lodge owner Michelle Titus had her guides teach these young people to fly fish, to encourage their engagement in the project and perhaps spark an interest in long-term jobs in outdoor recreation.

“This is a project that began around the legacy of our organization, around fly fishing, but it’s turned into something entirely different. It’s turned into reconnecting the Pit River tribe with their ancestral lands. It’s turned into a major socio-economic project in the Burney area. And it’s more than just fly fishing now. It’s about bringing all these people together to accomplish something that is valuable for them. We’ve learned as an organization that it’s all about bringing people together. People that are affected by water and fish issues in the regions where we work. We live in these communities, and bringing people together is the most important thing we can possibly do.”

- Drew Braugh, CalTrout regional manager for Northern California and Hat Creek project manager

Over the past fifty years, CalTrout has grown exponentially from the group of dedicated volunteers on Hat Creek to the $15 million organization of today. California Trout has established ourselves as the leader in California water and fisheries restoration, and we owe much of our success to those few who took it upon themselves to demonstrate that wild fish could be managed without dependence on hatcheries. These many years later, their impact is still felt not only on Hat Creek, but throughout the great state of California.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.