CalTrout v. Goliath

A Monumental Victory at Mono Lake

By Darren Mierau, CalTrout North Coast Regional Director

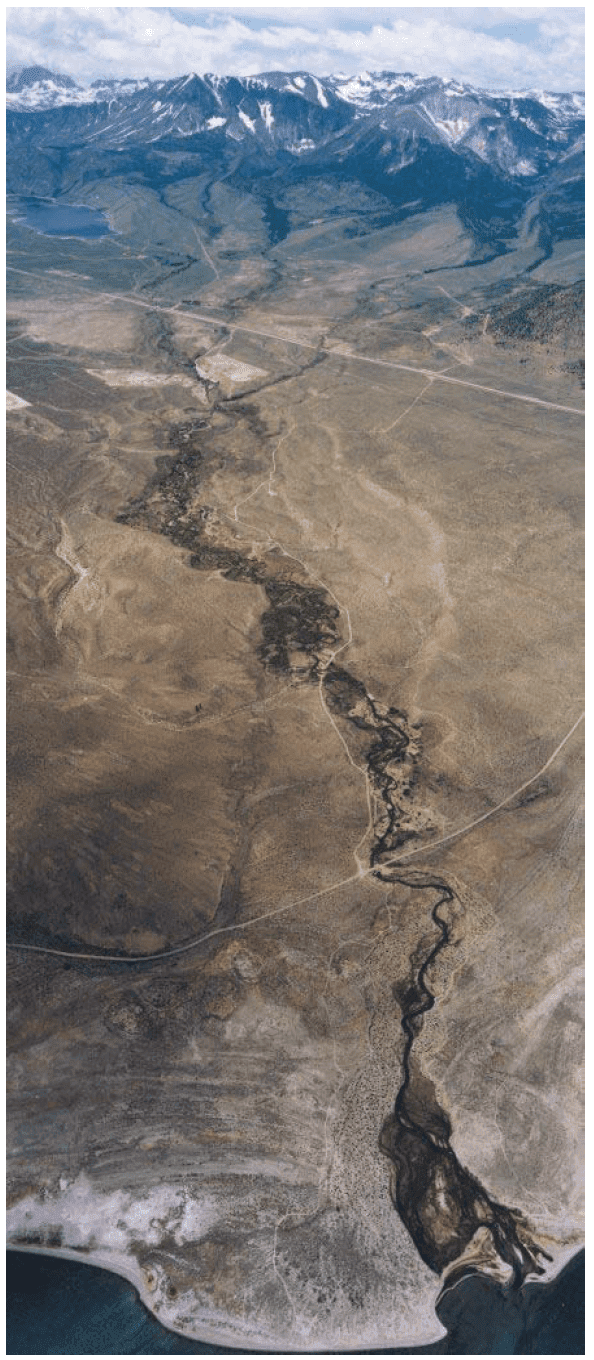

It's here where the fought-over waters that fill Mono Lake originate.

Most of California’s abundant Sierra Nevada snowmelt runs down the gently sloping foothills westward toward the Pacific Ocean. But for every 100 drops that run west, a few drops of that precious water escape down the much steeper “backside”, down the eastern slope and into the rain-shadow-lands of the Great Basin. Some of those drops end up in Mono Lake.

Coveted Waters

Mark Twain wrote in 1872 in his famous travel journal Roughing It, a century before CalTrout’s founding:

“Half a dozen little mountain brooks flow into Mono Lake, but not a stream of any kind flows out of it. It neither rises nor falls, apparently, and what it does with its surplus water is a dark and bloody mystery.”

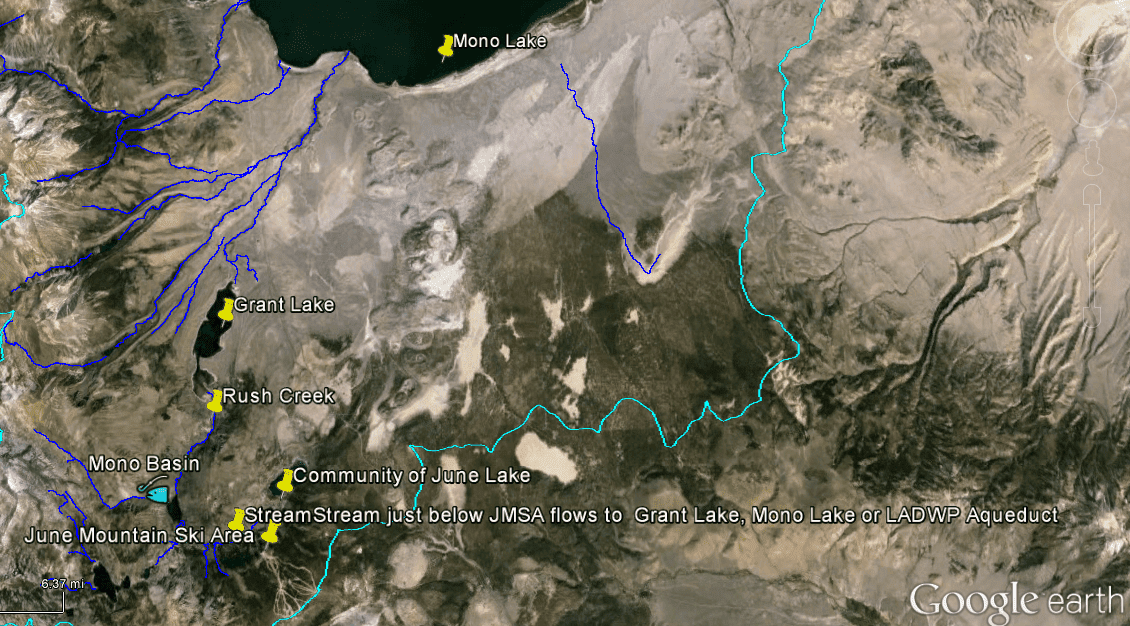

There are six Mono Lake tributaries to be exact - Rush, Lee Vining, Parker, Walker, Wilson, and Mill creeks. And the fact is Mono Lake never had any surplus water; its fullness has always depended on the amount of water running into it. So as soon as some of that water was cut off, which began in 1941, the Lake started to plummet and the entire ecosystem dependent on those “half a dozen little mountain brooks” soon followed.

The engineers of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) had long coveted the waters of the Eastern Sierra. As early as 1912, LADWP began purchasing land and water rights in the Mono Lake watershed. In 1923, they applied for a permit to “appropriate the entire flow of the Mono [Lake tributaries] for domestic use and power generation.” The two defining features of water in the Mono Basin, at least to LADWP surveyors, were its purity and its elevation (Grant Lake Reservoir is at 7,130 feet above sea level). Mark Reisner’s famous quote that in California “water runs uphill toward money” may be true enough, but it helps if it has a little momentum.

Mono Basin from the International Space Station, 2002

A dry Rush Creek. Photo courtesy of Mono Lake Committee

It only took until 1941 for the Mono Basin water to start flowing down south, first through the Mono Tunnel, down the Owens, into the LA Aqueduct, then the uphill part over the Tehachapi mountains, and finally to LA. Not long after, the results were apparent.

By 1979, Mono Lake’s surface level had receded forty-three feet below pre-diversion level, lost half its volume, and doubled in salinity. In most years, the four main tributaries, those “little mountain brooks” - Rush, Lee Vining, Parker, and Walker creeks - were dry most (if not all) year, and fish populations disappeared.

The Mono Lake ecosystem was collapsing.

CalTrout Gets Involved

To protect what we value, sometimes we have to undo things…undo environmental damage, undo water rights, undo dams. At CalTrout, we can do, and we can undo.

If Hat Creek was the birthplace of California Trout, the Mono Lake litigation was its precocious and spirited adolescence. CalTrout got its official start in 1972 and passed a decade of youthful exuberance. But by the early 1980’s the organization, with its leaders emboldened by its brethren the National Audubon Society and the Mono Lake Committee, was challenging not only the water rights possessed by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, but also the political power exercised by LADWP over one of the more influential state agencies - the State Water Resources Control Board.

The environmental goal of the 1980’s litigation was always clear: to save the Mono Lake ecosystem. In hindsight though, it is also clear this environmental outcome required not only undoing the 1940 water rights decision but also required the State to consider the needs of the ecosystem in its decision-making process. This was revolutionary, profound, and is now essential to modern-day CalTrout’s work.

Rush Creek in 2015

CalTrout I

In January 1989—in response to a suit brought by CalTrout, the Mono Lake Committee, and the National Audubon Society—the Court of Appeal ordered the state to review and ammend the water right licenses to four tributaries to Mono Lake. The ammended licenses had to comply with Fish and Game Code 5937, which states “The owner of any dam shall allow sufficient water at all times to pass over, around, or through the dam, to keep in good condition any fish that may be planted or exist below the dam.” This ruling, which became known as CalTrout I, ended nearly 50 years of LADWP using rights to divert without regard to impacts on the streams and their fish.

CalTrout II

CalTrout went back to court the following year, after the State Water Board proposed to undertake many years of study before amending the water rights. In what is known as CalTrout II, the Court of Appeal directed the State Water Board to immediately amend the water rights to require compliance with the Fish and Game Code, after which the Board would determine the long-term flow schedules. In 1994, the State Water Board issued Decision 1631, which established those schedules reducing LADWP’s historical diversions by 75%.

Taken together, these landmark cases not only restored four Eastern Sierra fisheries and began the process of refilling scenic Mono Lake, but they have also been instrumental in redefining the way dams are required to be managed and water allocated throughout the state. The precedent set by these cases has been used to establish public trust claims on natural resources and ensure future protection for California’s rivers.

Public Trust Doctrine

The Mono Lake case is best known for the precedent-setting use of the Public Trust Doctrine. This doctrine rests upon the principle that the public’s interest in certain natural resources is so important that these resources could not be transferred to private hands, but instead should remain freely available to the entire citizenry… and should be protected by the sovereign.

This is the essential beauty of the Mono Lake litigation, taking up the very foundation of environmental law - the Justinian Common Law principle of the Public Trust, which stated (in 534 AD), "By the law of nature these things are common to mankind – the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the shores of the sea" - and aiming that principle directly at the most powerful water interest in the western hemisphere: The Department of Water and Power.

“Successful litigants are generally those with a long-term view, who think strategically about the outcomes of the litigation, and implications of the litigation beyond the courthouse.”

– How the Law Mattered to the Mono Lake Ecosystem, William and Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review, Vol. 35

Rush Creek from Grant Lake all the way to Mono Lake

Science Leads the Way

A much lesser-known outcome also resulted from these cases, which involved so much acrimony and conflicting science in the early days. And that is a commitment to use best available science as the basis for stream restoration. Judge Finney (El Dorado Superior Court) oversaw interim flows and habitat restoration while the State Water Board amended the water rights, and he appointed a panel of independent scientists to guide these remedies. Two of those advisors were later named the “Stream Scientists” in the State Water Board’s historic Decision 1631 to oversee the restoration of Mono Lake and its “little mountain Brooks”. One of those Stream Scientists, Dr. Bill Trush, defined the goal for the Mono Lake program as “restoring the capacity for self-renewal”. In Dr. Trush’s 2017 essay on the topic, he asks:

“When will we know that the capacity for self-renewal in Rush and Lee Vining creeks, and throughout the Mono Basin, has been achieved? In some ways, I think the capacity has already arrived, through the tireless diligence of many. However, the one prime recovery ingredient for which we have no authority or leverage is time. The closest we can hope is assuring ourselves and all interested parties that the recommended actions will produce the desired ecological outcomes on which self-renewal relies.”

More narrowly speaking, the desired outcome for CalTrout I and II should be “Fish in Good Condition” (ah... let’s dream of those 16-20 inch brown trout). I asked Ross Taylor, the SWRCB fisheries Stream Scientist, if that had yet been achieved. Ross explained that the condition of the brown trout fishery in Rush Creek below Grant Lake Reservoir is highly dependent on runoff year type and reservoir storage levels going into the summer months:

“Periods of drought will most likely continue to negatively impact the fishery in terms of population size, growth rates and condition factors. However, after the recent five-year drought, the fishery exhibited resiliency and bounced back quickly in both the numbers of fish and their condition. Changing climate and variable snowpack conditions in the eastern Sierras will dictate the long-term fate and viability of Rush Creek's brown trout fishery."

The State Water Board is now considering a settlement between CalTrout, our partners Mono Lake Committee and California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and LADWP to end the Mono Lake Cases. The settlement uses decades of science data and predictive models to adapt Decision 1631’s flow schedule. CalTrout’s long-time attorney in these cases, Richard Roos-Collins, said: “These water rights will be living licenses, a first in California’s history. Flow management and evolving science are fully integrated to restore good conditions in these streams.”

It appears that nature—and not LADWP—is now back in the driver’s seat as the main influencer of trout condition.

Of course, in a legal settlement and the ensuing restoration program, compromises are necessary, and some were made. But the final questions that remain, I think, are: “Did we get it right? Were the ecological values, so hard fought for, protected? Will the stream ecosystems once again sustain that magnificent trout fishery that existed before 1941? And, has use of the Public Trust Doctrine and the Fish and Game Code provided an impetus for other environmental victories, as important precedents should?

In all cases, the answers are an affirmative - YES!

And with that, CalTrout graduated to adulthood.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.