The Committee of Two Million

Saving California's Wild & Scenic Rivers

By Bill Quinn, CalTrout founding member

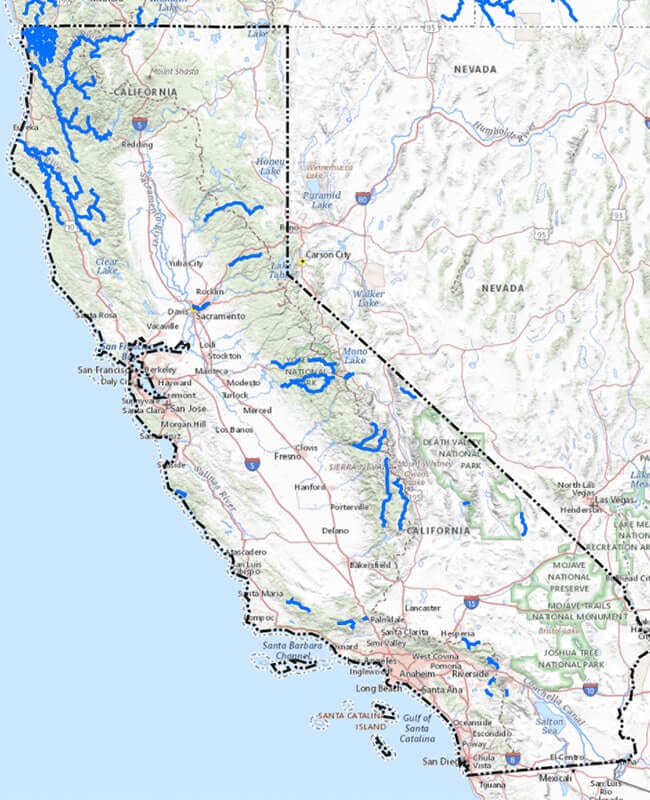

Nearly 2,000 miles of CA rivers are currently designated Wild & Scenic

The California Wild & Scenic Rivers Act—signed into law by Governor Ronald Reagan in 1972—has had a profound influence on some of our state’s most precious waterways. As a small group of passionate (and, dare I say, young) volunteers who were the founding members of California Trout, our journey from indignation over an ill-conceived state water plan to celebration over a major legislative victory was one that paved the way for the powerhouse organization that we know and love today as California Trout.

The Fight Begins at Dos Rios

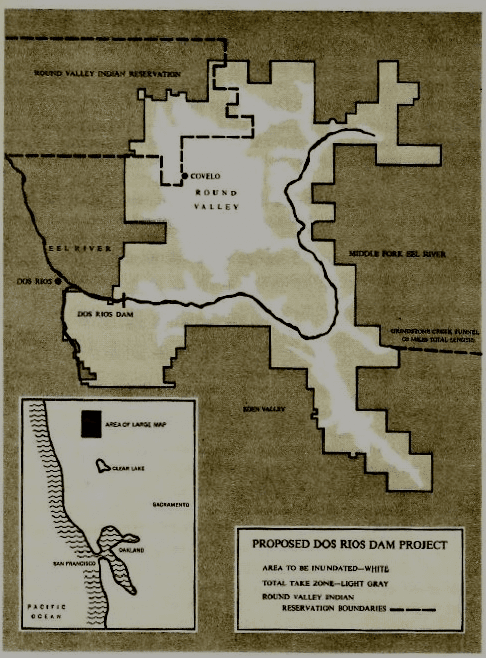

Back in 1967, the US Army Corps of Engineers proposed to build an enormous dam just above the confluence of the Eel River and the Middle Fork Eel River at Dos Rios. The Dos Rios Dam would be 730 feet tall to create a reservoir that flooded 110,000 acres of land, including the Round Valley Indian Reservation, the town of Covelo, and the watershed’s primary agricultural area. The plan would send water from the Eel through the Central Valley, past Sacramento, down the California Aqueduct, and on down to Southern California. And, of course, block native Chinook salmon and steelhead trout from their spawning habitat. In other words, it would have spelled disaster for the entire watershed.

After two years of raising alarm bells, the outcry from local residents finally registered with the powers-that-be, and Governor Reagan withheld his approval of the Dos Rios dam in 1969, citing a lack of alternative plans to the massive dam.

With this narrow victory, the Dos Rios dam was at least temporarily blocked. But the writing was on the wall, in terms of the future of California water. As a fledgling group of activist anglers in the Bay Area (not yet officially CalTrout), we knew someone had to step up to protect our watersheds from devastation.

It was then that our real work began to take shape.

Opportunity Knocks

It was about that time that State Senator Peter Behr was first elected to office, in 1970. He called Joe Paul (our early ringleader) out of the blue one day, and asked him if we’d support a state “Wild & Scenic Rivers” program, modeled after the federal program that had just been established two years prior. We didn’t even know Senator Behr at the time, but we sure liked the idea.

I was in my early 20s and already interested in water issues, serving as the chairman of the Water Resources Committee of Trout Unlimited before we officially formed California Trout in 1971. The previous governor, Edmund “Pat” Brown, had developed what was known as the California Water Plan, which I had studied well.

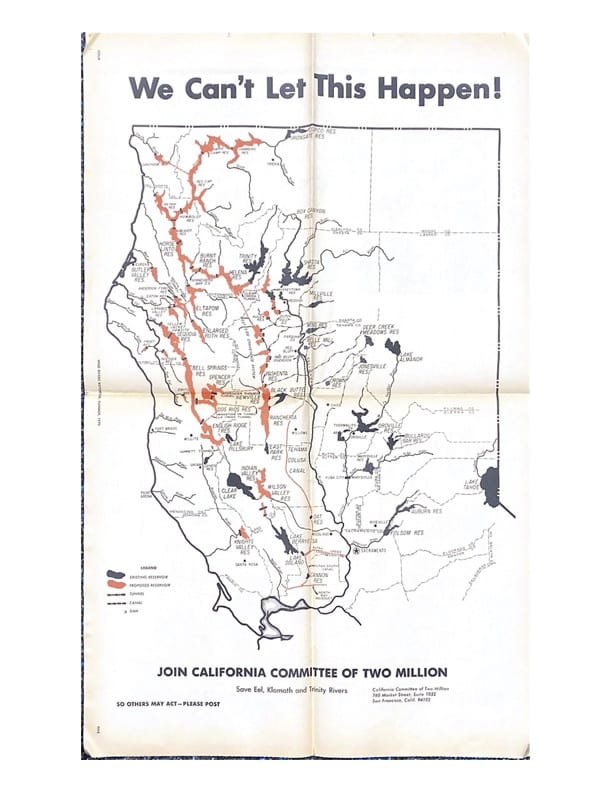

To put it bluntly: it was preposterous. The plan proposed projects that would have absolutely ruined the Klamath, Trinity, and Eel Rivers with dams that would divert water through tunnels dug into mountains and release it into the Sacramento River, where it would then be diverted farther south.

Senator Behr’s bill, SB107, would stop such a calamitous plan by restricting the creation of any new dams or diversions on designated “Wild and Scenic” waters. That sounded good to us.

Now, people weren’t as environmentally conscious then as they are now. Most people didn’t pay much attention to the plan, or even know about it. And, of course, there was no social media to spread the word. Today, just a whisper of such a plan would provoke public outrage, and you could spark the flame from your desk with a single tweet. Back then, we had newspapers. But the Chronicle, the Sacramento Bee, Mercury News, Southern California papers – they were all very reluctant to print anything that pushed back against the water plan.

So we knew we had to come up with a way to capture the public’s attention, to gain their support for the bill, and we had to do it ourselves.

Joe Paul—who eventually became CalTrout’s first President—was a PR guy, and it was he who came up with the plan to build a grass roots movement to pressure Sacramento.

First, we needed a name for the effort. Something that communicated the broad coalition we were trying to form. We came up with the Committee of Two Million (or CCO2M), named after the number of licensed anglers in California at the time.

Next, we needed a message. As I mentioned, people at the time weren’t so aware of environmental issues. And we knew that most people would never actually see these places in far northern California. We would have to not only show the folly of the Water Plan and the damage it would cause, we would have to sell the idea that these rivers need to be preserved – that they should remain in their natural, pristine condition - not just for us, but for future generations to come.

And boy, did we sell.

I went to Lions Clubs, Rotary Clubs, Kiwanis Clubs, fly fishing clubs—I must have spoken at just about every single one in Northern California, to get them to support CCO2M and SB107. I brought with me a huge map—as big as a projector screen—with all the existing state reservoirs, water facilities, canals, diversions, etc. in blue; and in red, all the proposed actions—dams on the Klamath, Trinity, and Eel Rivers; tunnels and canals carrying that water all the way to the Sacramento River. When you saw it on the map - it was so grandiose, it was ridiculous.

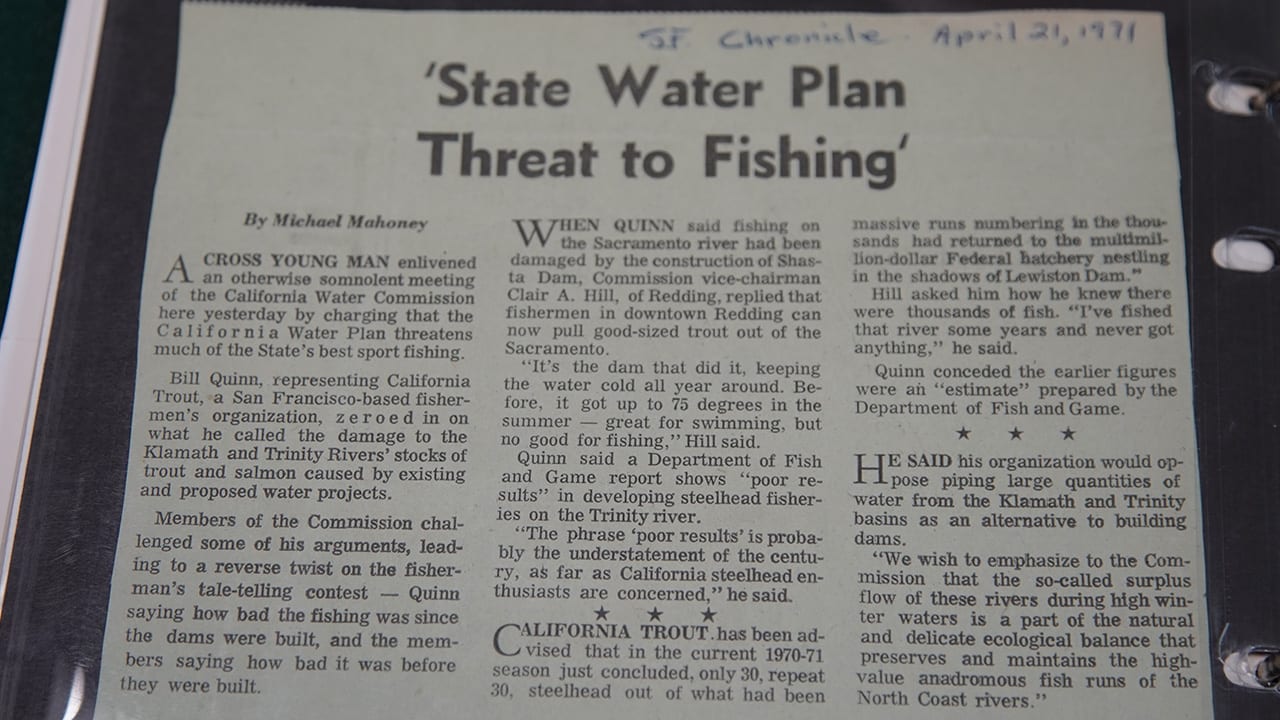

I went on local TV and spoke before committees, as well, and Joe Paul was instrumental in helping me craft our message. He had a phenomenal ability to frame ideas in a way that people would accept them. I can remember once I was to speak before the California Water Commission. Joe gave me a script to read and said, “You watch; you’ll be in the newspaper tomorrow.” Sure enough, there it was in the Chronicle the next day: “Cross Young Man” testifies before the Commission.

We spent a lot of time down in Southern California, too. We would fly down—Richard May, Joe Paul and myself—making presentations to anyone who was willing to listen, before flying back home to the Bay Area. Back then, you could catch the “midnight flyer” with PSA. You just walked right up to the door with a $10 bill in your hand, gave it to the stewardess, and off you went back to San Francisco. It was usually just us and a bunch of hippies on board. They’d see us in our suits and ties and say, “this must be the bankers’ section back here.”

And then, suddenly and overwhelmingly, Joe Paul died. But rather than give up after the loss of our charismatic leader, we picked up the mantle and carried on.

Hard Work Pays Off

“We took on what Joe Paul had left behind, as far as the war for the rivers.” – Richard May

It took two years of steady campaigning and the support of many, but we finally got AB107 to the Senate floor in 1972, and the California Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was passed.

Richard May and I spent a lot of time walking the halls in Sacramento, trying to gain support for the bill before the vote. It was a different world back then; Democrats were still in control, but you didn’t have both parties beating each other up. Politicians were issue-oriented; no matter the party, they were willing to listen.

The Feds Step In

A few years later, as it happens, an aide to then-Governor Jerry Brown called up CalTrout and said, “hey, you know there’s a provision in the federal Wild and Scenic Rivers Act that allows the governor to petition the federal government to add state-designated wild rivers to the federal system?”

Well, that was more welcome news to us. And as the story goes, as the Carter Administration was in its final moments, Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus was hustled away from a late night going-away party, and brought to his office by our D.C. lobbyist in order to sign the Order into law.

Today, about 2,000 river miles along 26 of California’s rivers are included in the state and federal Wild and Scenic River systems. Sadly, that’s only 1% of our state’s river miles, and there’s much work to be done. Nonetheless, that’s 2,000 miles of free-flowing river that are protected against dams and diversions, providing spawning habitat for our native anadromous fish, and ensuring that these pristine waters will remain for future generations to come.

Thinking back now on what we achieved and how, I’m reminded of a big meeting I attended down in Pajaro Dunes, trying to rally support for what would become the California Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. It was a wild group of diverse interests, from Southern California water districts to environmentalist groups. There was a “meeting facilitator” there who was hired to run the show. A total hippy. I thought, “what’s this guy doing here?” But he taught me something incredibly valuable that day. We all got in the room to have this meeting, everybody’s chatting, I thought, “Why’s this guy waiting so long to start this meeting?” He says to me, “every meeting starts with the ‘meeting dance.’” You’ve got to let everybody get a few things off their chest, get to know the person next to them. After that, you can disagree with them, but it doesn’t mean they’re a bad person.

Learn more:

Public Policy Institute of California: California's Wild and Scenic Rivers Act Hampers Shasta Reservoir Project

Rivers.gov: California rivers in the federal Wild & Scenic system

Wild and Scenic Owens River, credit: Scott Garrison

It was tremendous, really, what we were able to accomplish. It took real effort from lots of organizations and many people. You can see it in the photo of Governor Reagan signing the bill in 1972 – it was a very diverse group of interests: ranchers, the League of Women Voters, a California Water Commission member from Redding. It shows you what you can accomplish when people listen to each other and work together.

It’s what made us successful as the Committee of Two Million, and it’s what has made California Trout successful over the ensuing 50 years. And it’s what will continue to make CalTrout successful over the next 50.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.