MEET THE AUTHORS

Peter Moyle is the Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology and Associate Director of the Center for Watershed Sciences, at UC Davis. He is author or co-author of more than 240 publications, including the definitive Inland Fishes of California (2002). He is co-author of the 2017 book, Floodplains: Processes and Management for Ecosystem Services. His research interests include conservation of aquatic species, habitats, and ecosystems, including salmon; ecology of fishes of the San Francisco Estuary; ecology of California stream fishes; impact of introduced aquatic organisms; and use of floodplains by fish.

Robert Lusardi is the California Trout/UC Davis Wild and Coldwater Fish Researcher focused on establishing the basis for long-term science specific to California Trout’s wild and coldwater fish initiatives. His work bridges the widening gap between academic science and applied conservation policy, ensuring that rapidly developing science informs conservation projects throughout California. Dr. Lusardi resides at the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences and works closely with Dr. Peter Moyle on numerous projects to help inform California Trout conservation policy. His recent research interests include Coho salmon on the Shasta River, the ecology of volcanic spring-fed rivers, inland trout conservation and management, and policy implications of trap and haul programs for anadromous fishes in California.

Patrick Samuel is the Conservation Program Coordinator for California Trout, a position he has held for almost two years, where he coordinates special research projects for California Trout, including the State of the Salmonids report. Prior to joining CalTrout, he worked with the Fisheries Leadership & Sustainability Forum, a non-profit that supports the eight federal regional fishery management councils around the country. Patrick got his start in fisheries as an undergraduate intern with NOAA Fisheries Protected Resources Division in Sacramento, and in his first field job as a crew member of the California Department of Fish & Wildlife’s Wild and Heritage Trout Program.

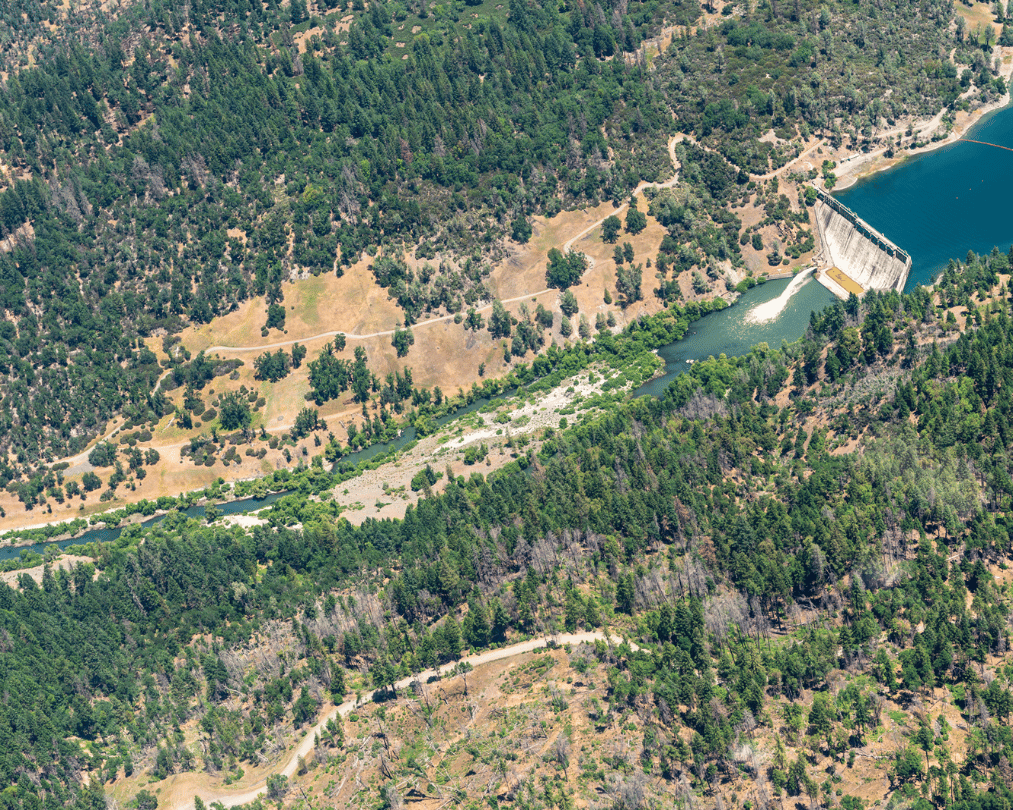

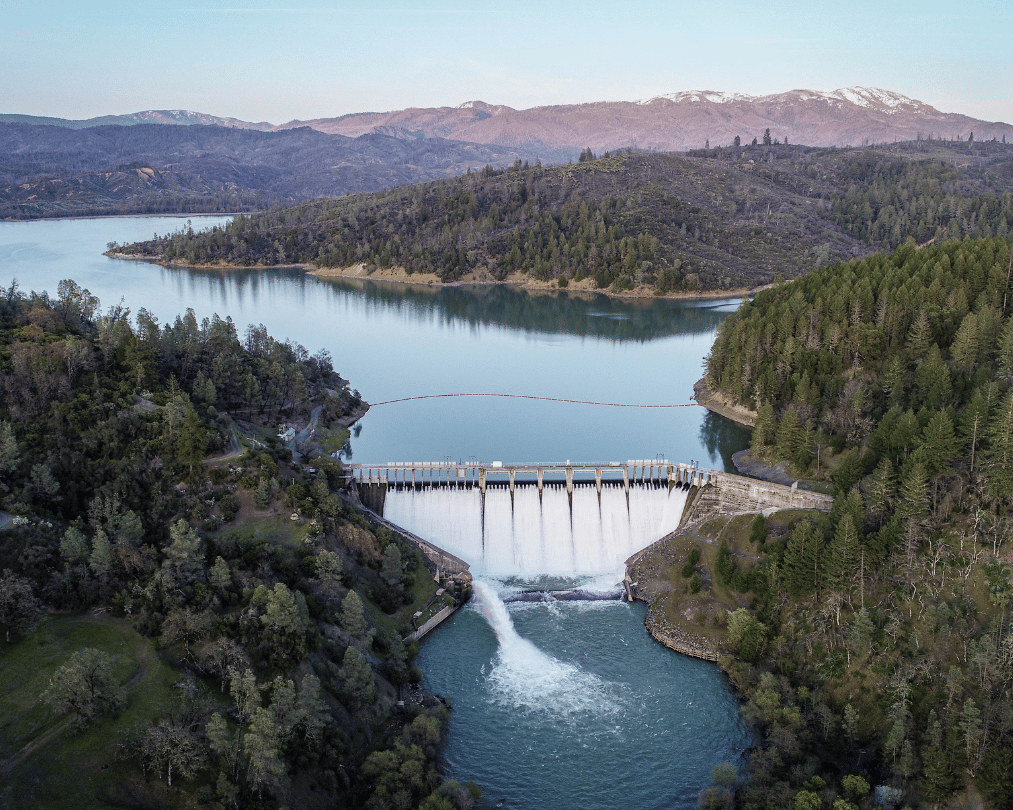

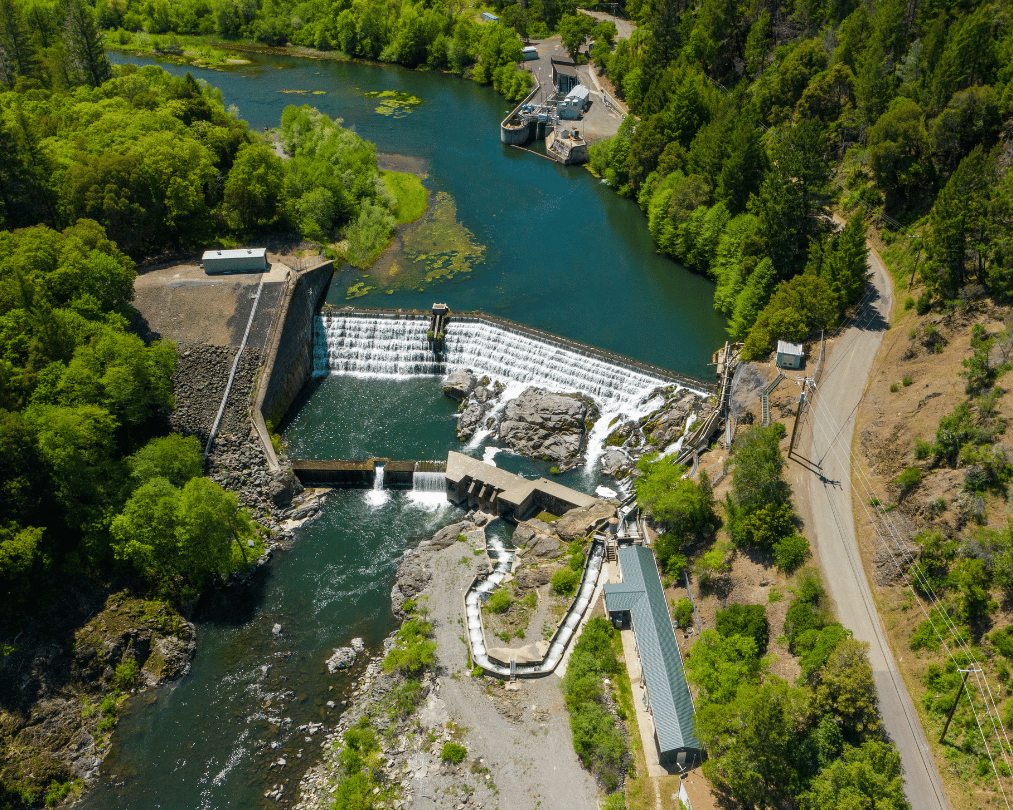

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.