A Field Note from Touring Malibu Creek Watershed

by Christine Walker

First, a word of advice. Definitely retrace the spawning journey of the Southern steelhead up Malibu Creek in the sweltering grip of a thermal heat belt.

Well, maybe not, but without a doubt, things you understand intellectually are felt more keenly in triple digit heat. Things like: Even before a 100-foot dam stood in the way, the steelhead that ran this creek must have been impressive. LA drivers are not joking around. This is a precipitously steep valley. Climate change is real. Water is life.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

As most reading this know, we have lost 90% of the wild fish that used to navigate our rivers and streams in California. Here on the South Coast, steelhead populations have dwindled into the single digits and extinction is a very real threat.

CalTrout has been studying the causes and remedies for the shocking decline in wild fish for over 50 years and updating our Save our Salmonids (SOS) report as a roadmap back to wild abundance. Five initiatives came out of that report, one of them – Reconnect Habitat – calls for us to remove barriers to fish migration to and from the ocean and their spawning habitat.

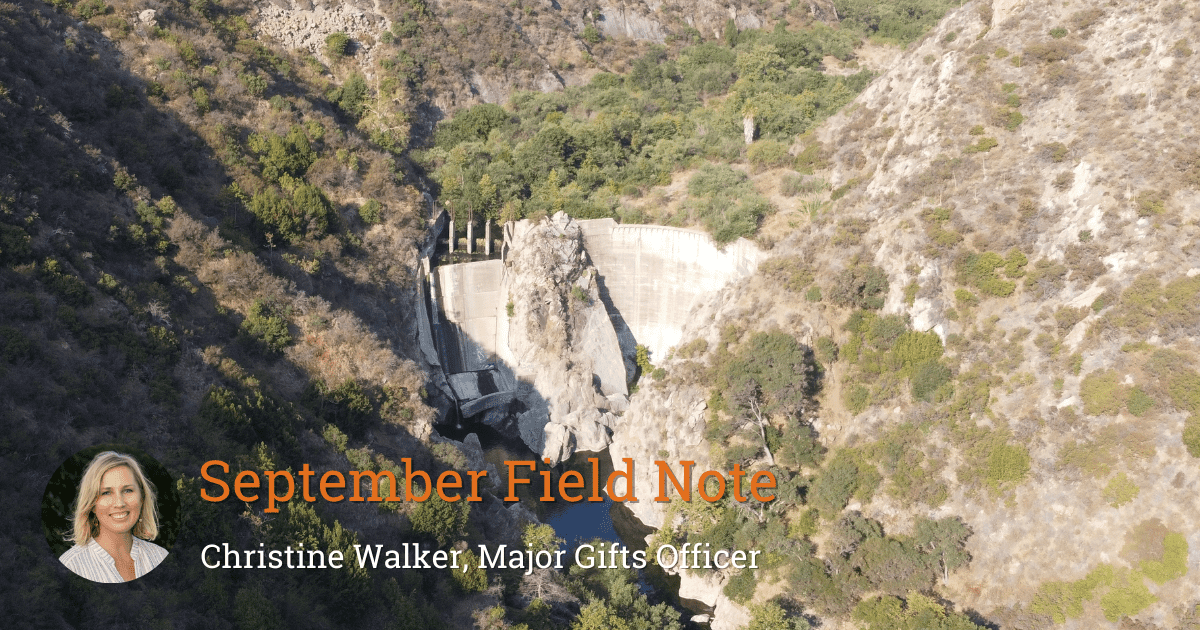

In this case, the barrier is the 100-foot Rindge Dam. To understand the adverse effect it has had on Malibu Creek, we started our tour at the lagoon where the creek meets the ocean, the Chumash ancestral home of Humaliwo - where the surf sounds loudly. It was a very pleasant 82 degrees and you looked out past a restored wetland to a world-famous break that used to curl unbroken all the way down to the Malibu Pier barely visible in the distance. Russell Marlow, our South Coast Project Manager, reminded us that the dam is not just trapping water and migratory fish that would make their way to this inlet but approximately 780 thousand cubic yards of sediment that would have been nourishing this habitat since its construction almost 100 years ago.

Now a World Surfing Reserve, Malibu Lagoon had become a severely impaired water body until a State Parks-led restoration effort in 2012 that effectively removed pollutants and recontoured the channels. The monitoring efforts used to gauge the success of that project have seen endangered species return to the lagoon, including the Southern steelhead. Now, we want to re-open the path to their spawning habitat in the headwaters of the creek. Their journey is tough, this one will be too.

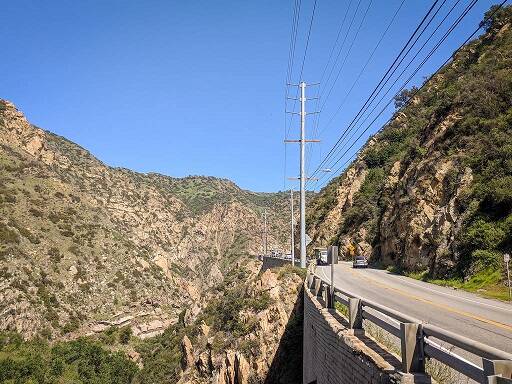

LA Drivers

From the lagoon we caravanned 3 miles up to Sheriff’s Overlook to see the dam. Before it was bisected by the Malibu Canyon Road, a two lane highway that is travelled by a lot of very rushed luxury vehicles (and, to my delight, one Chevy Malibu) this was the uninterrupted homestead of the Rindge Family. The ranch extended from the headwaters to the sea encompassing all that we now know as Malibu and much of the Santa Monica Mountain range. Here, the family built their homes and ran their cattle and built a big dam. As we know, that dam quickly held more sediment than water. Sediment that our South Coast Director, Sandra Jacobson, reminds us will have to be trucked out as the dam removal gets underway. 780,000 cubic yards divided by 10, the size of a dump truck, makes for a lot of trips. CalTrout and the many partners that have assembled to tackle this challenge acknowledge that managing sediment removal without disrupting this major thoroughfare will be of paramount importance.

Precipitous

The temperature rose as we did and reached above 110 when we pulled out at the unmarked overlook. Some goat trails led down to the dam where you could just barely make out a few, we’ll call them brave, swimmers. Sandra picked up the story of the Rindge family and took it through to Malibu Creek State Park management and talked about the act of Congress that allowed the Army Corps of Engineers to evaluate the feasibility of dam removal and select a locally preferred plan, a process many years and appendices in the making. That brings us to today – the design phase. While still eight years from breaking ground, this is a watershed moment, no pun intended. As Sandra was talking about stabilizing intense lateral pressure a CALFIRE helicopter buzzed by and I was transported, the M*A*S*H* theme played through my mind before I could rationally place the valley as the set of that and, I later confirmed, about 150 other movies and television shows. For roughly the cost of two feature films, we can restore this mythic valley.

A Changing Climate

I know anecdotal evidence is not a good way to talk about a global phenomenon but a 96 degree low temperature like the one they measured on the night we were there is worth mentioning. Better evidence for the major beach losses that will occur in Southern California because of sea level rise can be found in the Journal of Geophysical Research, CalTrans Vulnerability Assessment and elsewhere. Although removing Rindge Dam alone will not protect homes within the danger zone, that 780,000 cubic yards of sediment could have been working slowly, as nature intended, to nourish and protect the Malibu coastline, one that is particularly narrow and vulnerable. Some California dams still provide net benefits like water storage and hydropower but so many, like Rindge, are completely obsolete. These dams must come out so that the rivers can do their jobs.

Water is Life

Up above the dam we made our last stop at Malibu Creek State Park. The water rushed under a narrow concrete culvert, one of several smaller barriers that will also be removed as part of this project. The group took refuge in the shade of the willows and went down to touch the water and guess at its temperature. The air temperature was well up toward 114 degrees at this point and the improbable flow seemed like a perfect sanctuary for a smolt. Legend has it that the Rindge family could catch enough fish in the creek to entertain unexpected guests on any given day. Their bounty came to an abrupt end when, fueled by Santa Ana winds, the insular compound was destroyed by wildfire in 1903. Fire remains a major threat in the area, as we are reminded by the vigilant helicopter circling above, and its impact is felt in the water quality long after the flames are extinguished. I could go on about the importance of functioning water systems for fire management, habitat, sediment flow and more but I think Sylvia Earle said it best “No water, no life. No blue, no green.”

Get involved:

Submit your comment to CDFW to support Southern steelhead protection.

Read more about our efforts to Reconnect Habitat around the state.

Become a member of CalTrout.