Last spring, Sean Jansen, freelance writer and overall outdoor junky, began hiking. His route? A 1,000-mile circumnavigation of the entirety of Southern California steelhead’s historic range, from the California-Mexico border to the Central Coast.

Born and raised in San Clemente, Sean was always torn between two worlds: surfing and trout. These two things hardly ever seemed to cross over; until he discovered that there are steelhead trout swimming in those same waters that he surfs in. As he learned more about Southern steelhead and their migration routes through his home waters, he also began to learn about the disruptions to those routes and how these fish were teetering on the brink of extinction. In response, Sean dreamed up a trip where he could backpack the extent of Southern steelhead’s historical range raising awareness about their plight along the way.

Southern steelhead once thrived with tens of thousands of them swimming through Southern California waters, but today, it is rare to see even a few. They are listed as endangered under both the federal and state Endangered Species Acts.

Last spring, Sean began his trip. This fall, he will complete the circumnavigation. From the places where these streams meet the sea to the ridgetops where they originate, he will be covering each mile of historic Southern steelhead habitat. Along the way, he will encounter barriers to migration, opportunities for habitat restoration, and the raw resilience that these fish embody as they continue to fight for their lives in one of the most densely populated regions on earth.

As he mimics the migration paths that these fish must swim to survive, he discovers just how miraculous their journeys are. Sweltering temperatures, intense mountainous terrain, parched streams, and concentrated urban development are just a few of the threats that Sean – and Southern steelhead – must contend with. Migrate with him as he recounts his journey thus far – starting along the coast – and stay tuned for more updates from his journey and for the circumnavigation to resume next month! Learn more about why Migration Matters here.

Part 1: The Coastal Route

by Sean Jansen

Most expeditions in my life begin with nausea, nervousness, fear, and doubt. The night before thinking of the worst-case scenarios, “what if?” questions, and cold sweats. But not this trip. This trip started with joy, excitement, and a warm feeling in my stomach of what’s to come. I was home.

I grew up in San Clemente, a quiet little surf town nestled perfectly between Los Angeles and San Diego. There was only one thing on my mind each day growing up, and that was surfing. It didn’t matter if it was before school or after, before soccer practice or after, I went into the ocean every day of my youth.

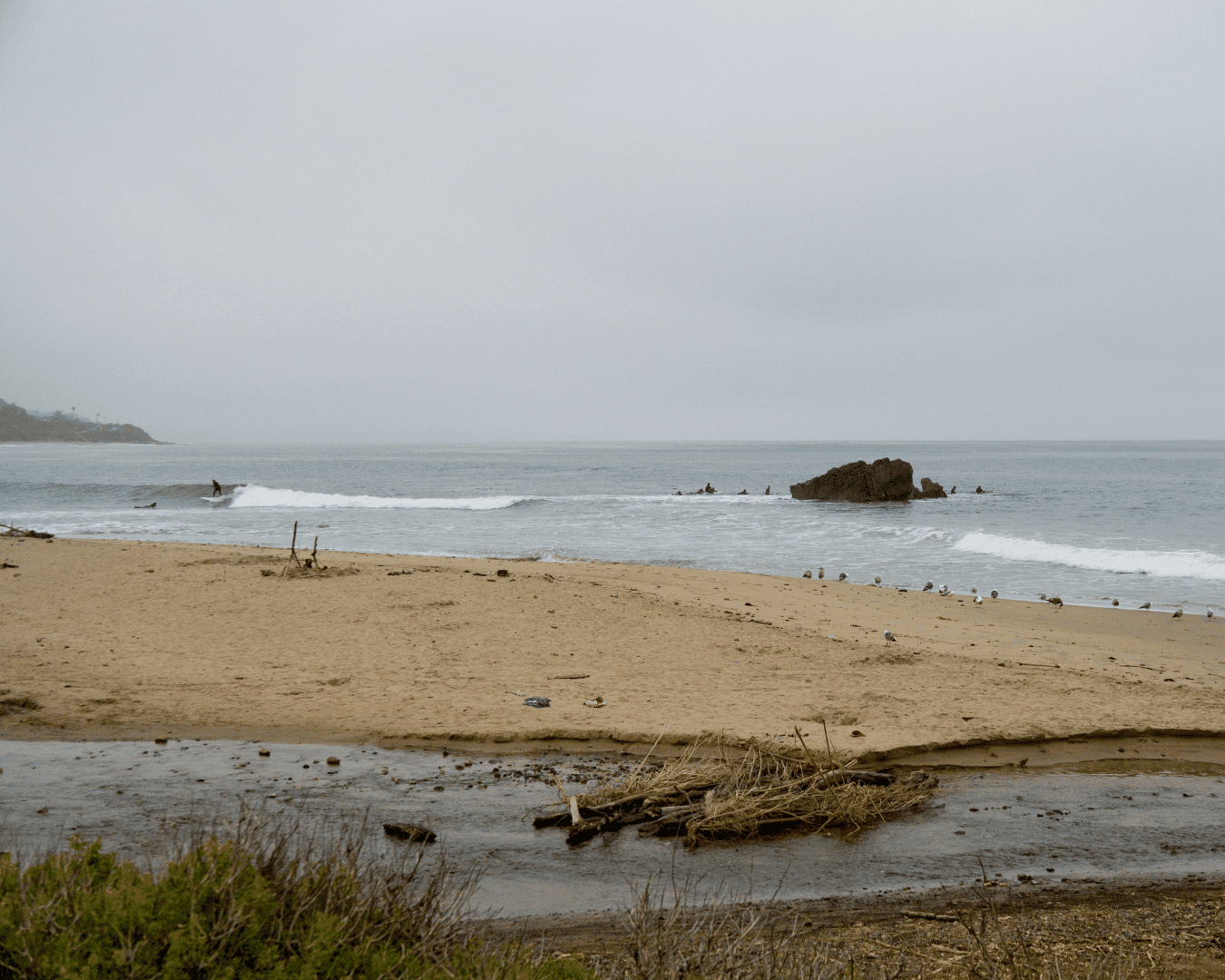

For over a decade this was my drumbeat. As soon as the class bell rang, no matter what the forecast called for, I was out there. But little did I know, that often the waves I was surfing, were that of river mouths. Places like Lower Trestles, a world-class wave that hosts world championships every year. A cobblestoned point with what I always thought as a kid to be a polluted lagoon at the base of it. But that polluted lagoon was special.

The only reason a wave like Lower Trestles exists is because of this lagoon. The lagoon is fed by a stream, and that stream hosts one of the most incredible fish this earth may have ever seen. A fish that waits for decades for that lagoon to breach to the sea so it can enter the ocean, grow into a large, salmon-like fish, and return to that same river to swim up stream and spawn. That fish is the Southern California steelhead. When I was young, I hadn’t a clue that while I was spending hours in the water surfing, these fish could have been swimming beneath my board, waiting for that polluted lagoon to breach during the next rain. Soon, I came to understand that they lived not only in my home waters, but all up and down the Southern California coast.

I began to meditate further on the subject to realize that there were other lagoons up and down the Southern California coast and each and every one of them, historically, had a population of steelhead. Pulling up Google Maps and zooming into the bite of Southern California, my creative wheels began to roll, and I came up with an idea to walk along the coast to every estuary, river mouth, and lagoon, while also exploring the rivers that feed them. All to feed my curiosity and enhance my understanding of these fish that lived in my backyard.

Scrolling further, the Pacific Coast Highway skirts the coast up to the northern most river of the fish’s range, the Santa Maria. I could then walk the mountain ranges via trails, including the infamous, Pacific Crest Trail, back down to the U.S./Mexican border to the Tijuana River. Then I could finish the trip, walking back up the coast to San Mateo Creek, the lagoon and the surf break I call home.

After visually seeing this in the browser of my computer while having the screen of my computer perfectly filled with the entire map of Southern California, I leaned back and stared at it, daydreaming of what I was potentially going to see. With my experience in the backpacking world, I failed to see how it couldn't be possible. So, researching further, I knew I could camp up and down the coast at the state parks that litter the coast, many of which are right on the banks of some of the historical waters of the steelhead, then I could stay at hotels in the metropolitan areas of Long Beach, Santa Barbara, and Santa Maria.

Before I knew it, I found a date that would work between my work schedule and timing it with when the rivers will have the most water, and on April 15th, I set off from my hometown and began walking the coast north. For the first three days, it was all about finding my groove and discovering what kind of mileage I could do. I’m a runner as my daily therapy, but walking with a backpack full of camping gear, food, and water is another realm of contact for my joints. I was in pain, but somehow managed to do 20 miles a day making it to the major shipping point of Long Beach.

The only way to navigate this major port was to follow the Los Angeles River and snake my way through one homeless encampment after the next. I was successful, but with each and every obstacle I faced with Ferraris zipping by, smog and pollution in the air, and trash and garbage in the storm drains that all lead to the rivers then out to sea, I couldn’t help but feel for these incredible fish that deal with this everyday of their life.

With a mix of what felt like forever as well as flying by faster than I would like, I found myself in the throes of the central coast and away from the wealth that encompasses the coast south from Santa Barbara. The concrete jungle faded away and the wilds of Southern California took over. I didn’t want to believe it myself, but I grew up in a concrete jungle of cookie cutter streets, parking meters, and coffee shops, and that turned to rolling green hills, oak trees, cool and clean water, and wildlife. Birds of prey flew the skies, wild boar foraged the landscape, and the paw prints of bear and mountain lion tracked the soil.

Navigating Vandenberg Airforce base and skirting Point Sal State Park, up on a bluff, I was offered sweeping views of the vast Pacific Ocean with the sand dunes of Pismo Beach off into the distance. But at the foot of the headland, down near the shore of crashing waves, the Santa Maria River lay stagnant as a lake with a blue lagoon, feet from shore, waiting for the rushing high tide to wash over and breach.

I had made it to the northern most section of the historic range of the Southern California steelhead, a task that took longer than expected and one that took more of a toll on my joints and body than expected. Dodging Lamborghini's, multi-million-dollar homes, and epic Mexican food, I had made it to the wilds of the central coast and the gateway to the next chapter of the project. This coast route took 21 days and over 300 miles. But now, the second leg of the trip was about to begin. I was to make my way inland to the mountains where these mighty rivers start their life and begin my trek along to the spine of the mountains south to the U.S.-Mexican border to the once mighty Tijuana River. But first, a long 15-mile walk along a shoulder-less highway to the foot of the mountains needed to happen.