Last spring, Sean Jansen, freelance writer and overall outdoor junky, began hiking. His route? A 1,000-mile circumnavigation of the entirety of Southern California steelhead’s historic range, from the California-Mexico border to the Central Coast. If you missed leg 1 of his journey, you can check it out here and explore why Migration Matters for both humans and wildlife here. Dive into part 2 below!

Part 2: Tideline to Alpine

by Sean Jansen

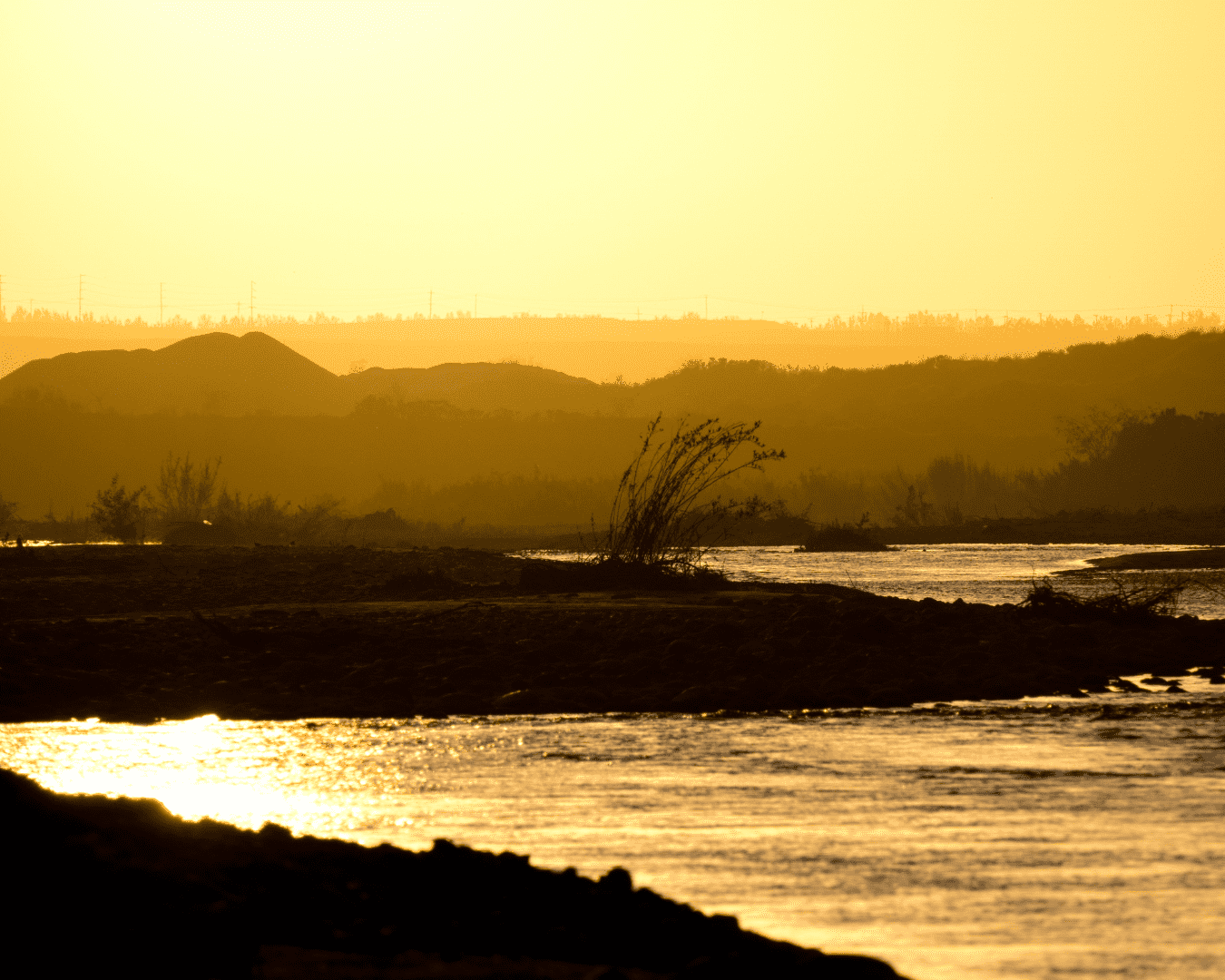

Reaching the Santa Maria River felt like a major accomplishment – over 300 miles of walking in just three weeks. The shift from the coastal landscape to the mountains was as sudden as switching from red to green at a traffic light, which was ironic because the further I traveled inland, the fewer traffic lights and man-made structures I encountered.

Walking the Pacific Coast Highway was a breeze in retrospect, with nice sidewalks, bike lanes, and the occasional coastal trail overlooking the sea. Grocery stores were at my disposal, drinking water was ubiquitous in stores and fountains, and I had easy access to hotel rooms and cell phone service.

All of that slammed to a halt the moment I entered the mountains and felt the dirt crunch beneath my feet. When that happened, I smiled. The dirt was the first thing I noticed, but before long, the silence took over. Long gone were the days of cars flying by an arm’s length away, horns blaring, and trains coasting as they cruised the shoreline. Now my playlist consisted of the sound of dirt crunching beneath my shoes, my breath slogging up the hill, and the birds of prey calling up in the sky.

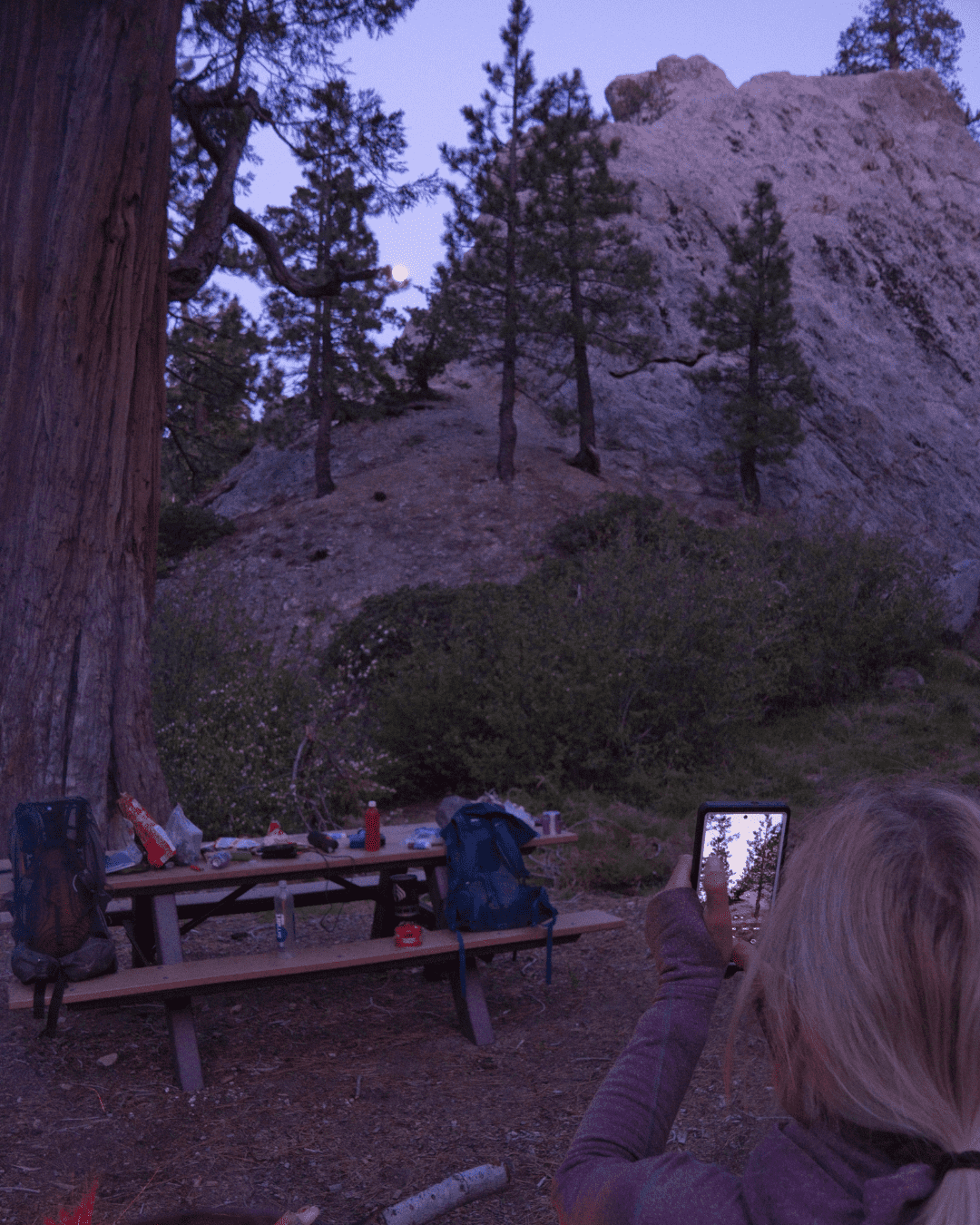

A partner joined me for this section of the trip – a refreshing break from my thoughts where we dove into our shared passion for backpacking into the depths of wilderness. Nothing but remote mountainous landscapes lay ahead, which was astounding considering we were only a stone’s throw away from well over ten million people.

At this point, my mindset shifted, and so did the mileage. We kissed goodbye to the days of 20-30 mile pushes until sunset, trading them in for about 15, and anything more than that was an added accomplishment. Each day needed to be meticulously planned around water access. Relying on the migration routes of Southern steelhead to guide our journey, we recognized planning was critical because while numerous, the creeks were spread out.

Now at elevation, I could see the fog-ridden coast below and the cool marine layer that had ensconced me for the primary part of my first leg. From above, it looked like a giant pillow or blanket covering the landscape, a snug escape from the wilderness. While comfort was desirable, I was reminded of the perilous migration of the steelhead – whose difficult journey is often further hindered by human-made barriers and obstructions.

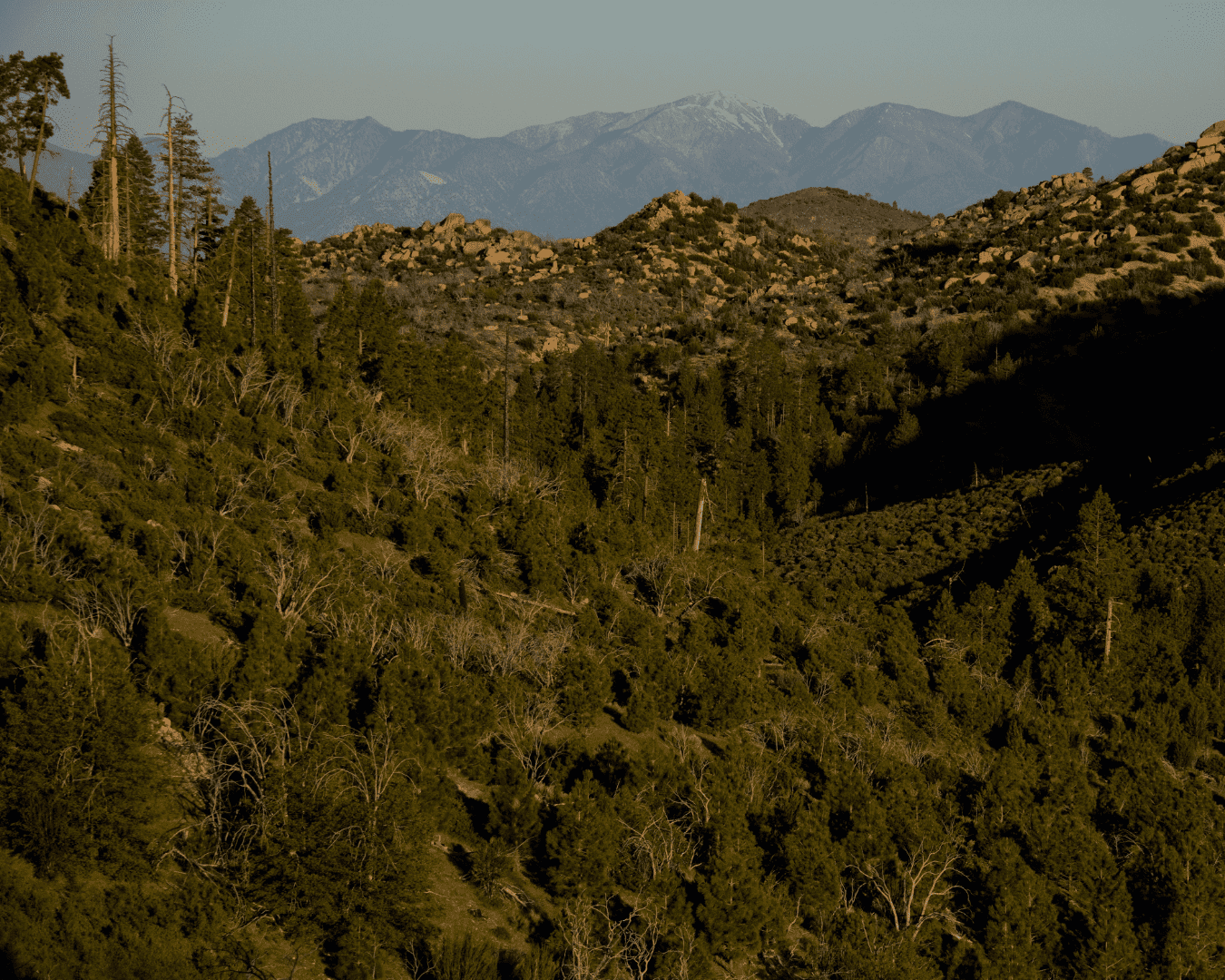

The coastal palm trees and occasional palapa from the state parks were switched out for the oak and pines that inhabit the alpine environments of Southern California. Many Southern Californians are unaware of the alpine wonderland tucked away in their own backyard, and this expedition offered a chance to unveil this hidden gem. Mountains with elevations ranging from 7,000 feet to well over 11,000 are less than an hour drive from Los Angeles, providing incredible hiking and scaling opportunities.

Even with it being late spring to early summer, snow blanketed the slopes of some peaks. My accommodations transitioned from hotels and paid camping to scoping out a flat spot in a bush that looked mildly comfortable. We hiked our way through one wilderness area to the next. Before long, we found ourselves on the Pacific Coast Trail (PCT), one of the most famous national, long-distance trails. A huge inspiration behind the entire trip was the ability and privilege to be able to hike many miles on this infamous trail. Spanning an awe-inspiring 2,650 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border to Canada, this iconic trail meanders through the diverse landscapes of California, Oregon, and Washington. More than just a hiking route, the PCT symbolizes the intricate connection between steelhead and human migration patterns. The life-giving waters that nourish the steelhead's epic journeys originate high in Southern California's mountainous spine, with the PCT weaving through this vital watershed like a great serpent. Our trek along this storied trail allowed us to witness firsthand the delicate interplay between land, water, and the creatures that depend on both.

Transitioning from bushwhacking and navigating the rugged terrain of the northwestern range of the Southern steelhead to the smooth, well-trodden path of the PCT felt like shifting from stop-and-go traffic to cruising in the carpool lane on a freeway. As the miles slipped by, we soon found ourselves alongside a steady stream of thru-hikers, all trekking north toward Canada. I loved being part of their journey, even as they looked at us with curiosity, wondering why we were heading south instead of joining their northern path.

As our journey progressed, I experienced a profound moment of realization, finally connecting the dots between the coastal waterways and their alpine origins. First came the Santa Clara, just outside Acton, California, followed soon after by the San Gabriel River. There was an indescribable thrill in witnessing both the birth and the ultimate release of these waters – observing where they first bubbled to life in the mountains and recalling their powerful confluence with the sea. This full-circle experience embodied the essence of this project, highlighting nature’s movement intrinsic to its very being.

With my work season about to begin, I departed the trail at the infamous ski town of Big Bear. With the Santa Ana River drainage in sight and Southern California’s highest peak looming in the distance, I’m eager to finish the journey.

My journey has not been without its obstacles. Ready to proceed with my bags packed and many miles ahead, three fires erupted during my time off the trail. The Bridge Fire which ignited September 8th, took to the hills that I had just hiked, wiping out 12 miles of the PCT, closing the area until December of 2025. September 5th, the Line Fire started and ignited much of my remaining route. The San Bernardino National Forest is slowly reopening, but I will likely need to wait until next fall to complete that section. Finally, the Airport Fire in Orange and Riverside Counties started as a spark from heavy machinery and closed many areas around San Juan and San Mateo Creeks, the origin to my home waters. This area will be closed until Fall 2025.

Throughout this project, I've encountered numerous obstacles beyond my control, yet I've always had the privilege of choice in how to navigate them. The Southern steelhead, however, face no such luxury. These resilient creatures confront a gauntlet of challenges hindering their ability to complete their natural lifecycle: raging wildfires, insidious pollution, scorching heat waves, the creeping effects of climate change, constant predation, and the relentless encroachment of urban development. My journey, while arduous, pales in comparison to their struggle to move freely and in turn, survive.

The reopening of National Forests remains uncertain, but when it happens, I'll return to the trail with renewed purpose. My goal is simple: to quietly trace the steelhead's path, connecting the dots of their journey. In doing so, I hope to honor their indomitable spirit and shed light on the critical importance of preserving their fragile ecosystem.