How we're working to save them:

Conservation Actions

- Expand projects that increase reliable quantities and quality of cold water habitat.

- Implement management and restoration projects that focus on reconnecting populations of Rainbow trout that are currently separated by barriers and promoting access to diverse habitats to restore genetic diversity.

- Support healthy populations of wild trout for catch-and-release recreational fisheries.

Click here to learn about CalTrout’s overall “Return to Resilience” plan to save California’s salmonids from extinction.

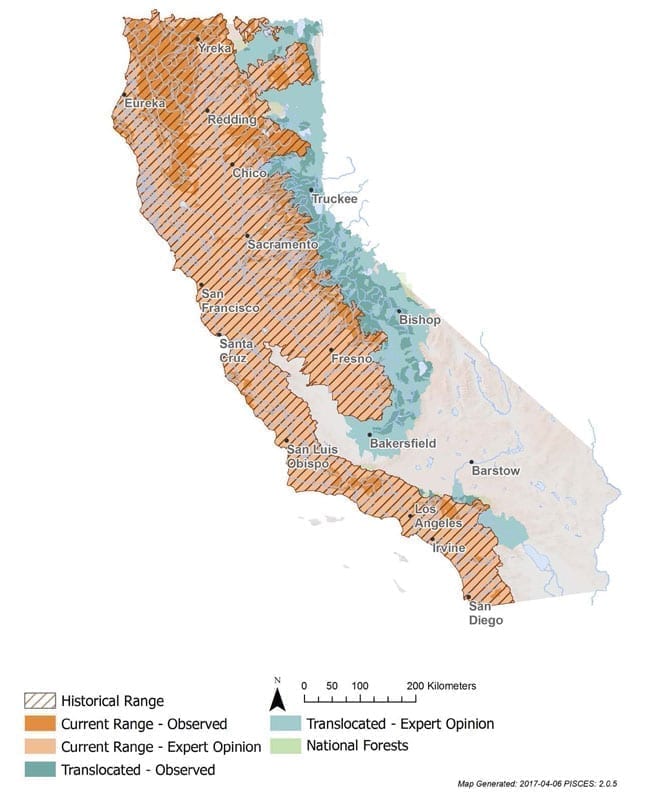

Where to find Coastal Rainbow Trout:

Coastal Rainbow Trout Distribution

Coastal Rainbow trout were originally present in virtually all perennial coastal streams from San Diego north to the Smith River (Del Norte County), and in most rivers in the Central Valley from the Kern River north to the Pit River near Alturas (Modoc County). Resident Coastal Rainbow trout were typically found upstream of natural barriers, such as waterfalls or rockslides, which were too difficult for steelhead to pass. Today, due to numerous introductions, Coastal Rainbows are found in virtually all streams where suitable habitat exists, including the once-fishless Sierra Nevada north of the upper Kern River Basin and lakes and streams in the Cascade Range and Trinity Alps.

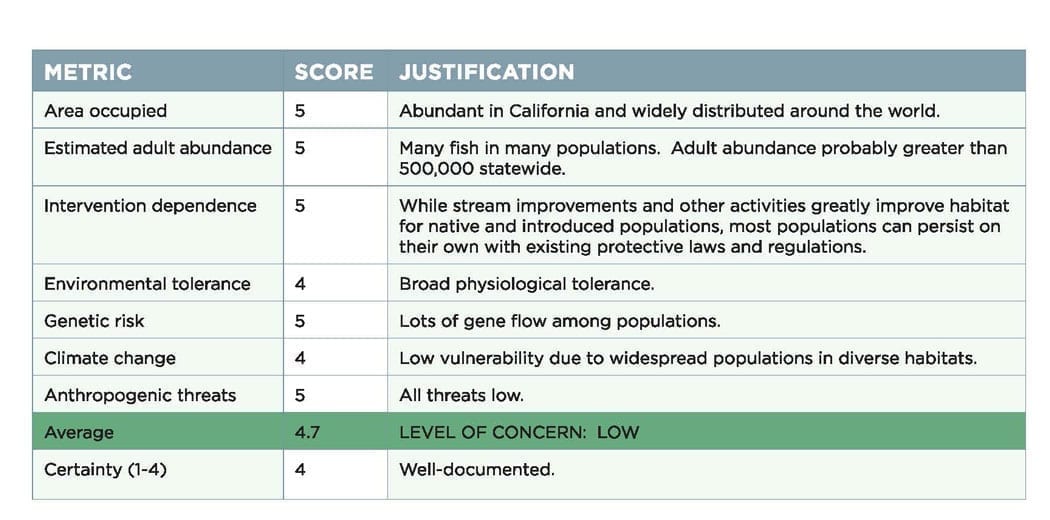

How the Coastal Rainbow Trout Scored:

Characteristics

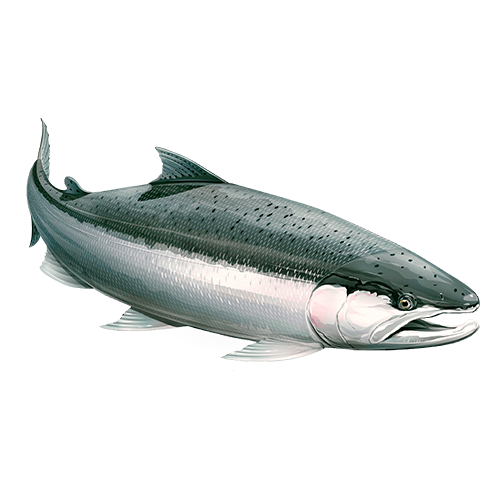

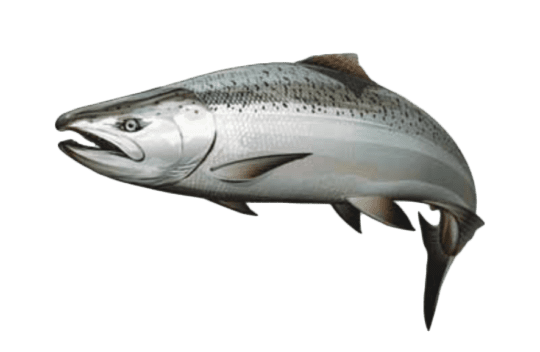

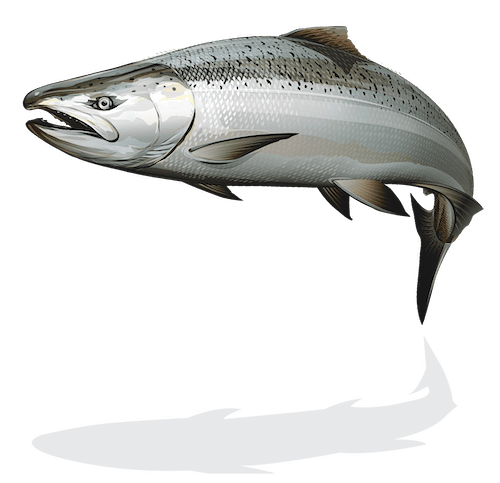

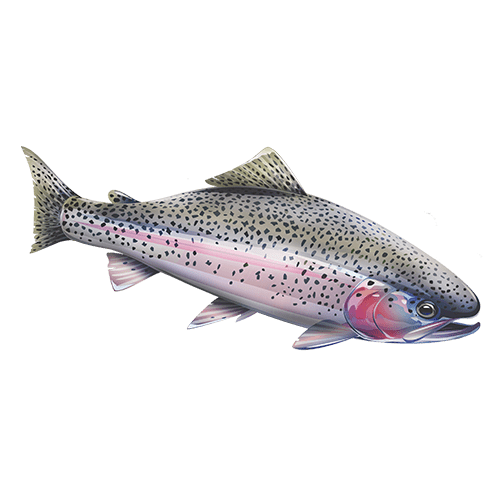

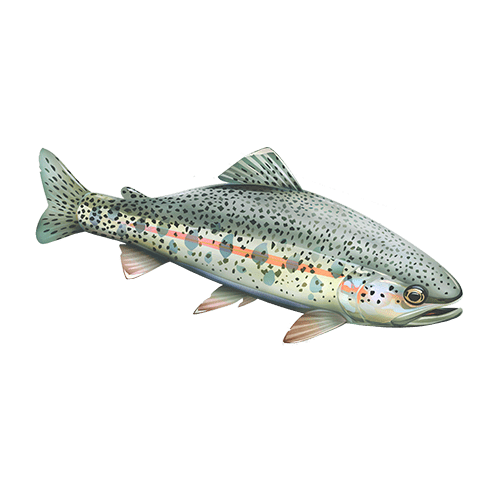

Coastal Rainbow trout are incredibly adaptable to different environments and are capable of exhibiting a wide range of coloration. Trout from small streams may be dark olive on the back with a yellowish belly and orange tips on the fins, while lake-dwelling fish tend to be more silver in color. Most Coastal Rainbow trout have heavy, irregular spotting, and spots that radiate outward in lines on the tail and a white belly. The pink to deep red band on their flanks gives the fish its namesake. In waters with access to the ocean, any rainbow trout greater than 41 cm (16 in.) in length are considered to be “steelhead” for management purposes and catch limits, although resident Coastal Rainbow trout regularly attain this size where habitat is favorable and food is plentiful.

Abundance

Wild resident Coastal Rainbow trout are more abundant today than they were historically in California due to a long history of introductions by pack mule trains, airplanes, and other means, especially into previously fishless high elevation lakes in the Sierra Nevada. However, Coastal Rainbow trout abundance across California was likely depressed during the historic drought (2012-16) based on drought rescue information from CDFW.

Habitat & Behavior

Coastal rainbows mature when they are two or three years old, and rarely live more than five or six years. They generally spawn in spring to early summer, from February to June depending on stream temperatures, but have been known to spawn during the winter months in Putah Creek (Solano County) and may spawn year-round in spring-fed streams such as the Fall River (Shasta County) without strong seasonal cues such as flow or temperature. Fish that spend their entire lives in fresh water rarely attain sizes greater than 70 cm (28 in.), but lake-dwelling fish may grow larger. In rivers and streams, they feed on aquatic and terrestrial insects that drift in the water column, and may occasionally eat fish and frogs, especially as they grow larger. They may feed on small invertebrate worms or insect larvae on the bottom of some rivers and lakes. In lakes and reservoirs, they frequently feed on fish such as Threadfin shad. Coastal Rainbow trout owe their success to their ability to adapt to a wide variety of habitats. They are capable of being stream residents, lake residents, or migratory between these habitats. Coastal Rainbow trout that express one life history are capable of having offspring that take on another life history if habitat is available.

Genetics

Coastal Rainbow trout are defined in this report as self-sustaining Rainbow trout populations that are (a) isolated above natural barriers as the result of geologic activity (landslides, waterfalls, etc.), (b) isolated above anthropogenic barriers, such as dams, and/or (c) introduced by people into isolated areas, such as historically fishless lakes of the Sierra Nevada. While all Coastal Rainbow trout likely had steelhead ancestors, populations upstream of major dams today have been found to be more genetically similar to other above-dam populations than they are to fish downstream of dams. Despite over a century of widespread stocking of hatchery strains of Coastal Rainbow trout in California, many populations above man-made barriers share relatively little genetic material with hatchery Rainbow trout.

- All

- _proof

- 50th

- Action Alert

- Bay Area

- Bay Area

- Blue Ribbon Waters

- California Water

- CalTrout People

- CalTrout Promo

- Campaigns

- Central Valley

- Central Valley

- Dams

- Diversity Equity Inclusion

- Eel River

- Event

- Events

- Featured

- Featured Watersheds

- Field Notes

- Fly Fishing

- From CalTrout

- Fun

- Hat Creek Restoration Project

- Imperiled Native Trout

- Initiatives

- Integrate Wild Fish & Working Landscapes

- Integrate Wild Fish & Working Landscapes

- Integrate Wild Fish and Working Landscapes

- Invasive Species

- Job Postings

- Key Initiative

- Klamath River Restoration

- Legal & Policy

- Legislation

- Migration Matters

- Mount Shasta / Klamath

- Mt. Lassen

- Mt. Lassen

- Mt. Shasta/Klamath

- News

- North Coast

- North Coast

- Podcast

- Podcast

- Press Releases

- Protect The Best

- Protect the Best

- Protect The Best

- Protect The Best

- Reconnect Habitat

- Reconnect Habitat

- Reconnect Habitat

- Regions

- Restore Estuaries

- Restore Estuaries

- Restore Estuaries

- Science

- Science Into Action

- SCRSC

- Sierra Headwaters

- Sierra Headwaters

- SOS Report

- South Coast

- South Coast

- Steelhead & Salmon

- Steward Source Water Areas

- Steward Source Water Areas

- Streamkeeper's Blog

- Trout

- Uncategorized

- video

- Voices of the Watershed

- Water Talks

- Women of CalTrout

- Youth

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.