Over the past two years, CalTrout and Inyo National Forest have been working together to restore and remove infested and dead whitebark pine trees on June Mountain. Dodds works as a Project Manager for CalTrout’s Sierra Headwaters region, and she leads the June Mountain Forest Health Project.

After a century of fire suppression, forests across the state have become densely packed and overloaded with dead wood that is primed to burn intensely and causes fires to spread quickly. By mimicking some of the effects of the natural fire regime, mechanical thinning selectively removes patches of dead forest and understory. On June Mountain, CalTrout and Inyo National Forest are working across 356 acres to realize a more resilient forest ecosystem for the benefit of the nearby community, wildlife, native plants, and inland fish.

Forest health and fish health are intimately connected, especially when wildfires occur. In forested watersheds, heritage and wild trout populations are increasingly vulnerable to the effects of wildfire including increased water temperature, decreased water quality, and increased runoff and erosion.

During the 2022 McKinney Fire, 60,000 acres around the Klamath River burned. A few days later, unrelenting rain assailed the fire footprint, pushing dirt and debris into Klamath River tributaries. Choked with mud, the river’s dissolved oxygen plummeted, and its aquatic denizens suffocated. The fish kill extended along a 30 to 40 mile stretch of the river.

On June Mountain, the threat of wildfire looms and a severe event would undoubtedly have a detrimental effect on the Rush Creek watershed and its wild trout population. CalTrout is working to provide more resilience to the watershed and its human and fish communities by reducing the risk of a catastrophic wildfire.

On June Mountain, the threat of wildfire looms and a severe event would undoubtedly have a detrimental effect on the Rush Creek watershed and its wild trout population.

CalTrout is working to provide more resilience to the watershed and its human and fish communities by reducing the risk of a catastrophic wildfire.

The June Mountain Forest Health Project

The June Mountain Forest Health Project began in 2016. Project implementation consists of three phases with the third phase currently underway. In 2022, the project team completed Phase 1, processing and removing over 2,000 tons of infested or dead cut biomass. That’s two cargo ships, 13 adult whales, or six Boeing 747 jets worth of dead trees! in 2023, Phase 2 was completed, and additional funding and acreage were added to the project from Inyo National Forest to begin Phase 3.

On September 5, the Phase 3 field season began. The intention for this phase of the project is to mitigate conifer encroachment within the meadow and aspen stands to restore aspen, whitebark pine, and meadow ecosystems. The project focuses on treating three different types of “units” or areas of the forest: meadow restoration units, aspen restoration units, and forest health units.

“Working with partners like CalTrout makes doing this work a lot easier,” said Becky Scanlon, a Forester with the Inyo National Forest. “They can bring in grant funding to help assist with the cost of some of these treatments which can get pricey with the diverse terrain we have here in the forest.”

CalTrout Project Manager Marrina Nation takes a soil sample.

Meadows Matter

The project’s benefits are twofold: it is a forest health project and it also a meadow and aspen restoration project. By thinning the forest, the project also helps restore nearby meadows.

“You can think of all the trees like little straws that are sticking up out of the meadow and sucking water out of it,” Dodds explained. “By removing some of these trees, there are less straws and thus less water leaving the meadow leading to a wetter and healthier meadow ecosystem.”

Like the mountain snowpack that Californians depend on for year-round water, healthy meadows store water and release it gradually. They also filter out pollutants in the process. As the climate warms and scientists project more rain and less snowfall in these mountain ranges, Sierra meadows will become an increasingly important resource for water storage. Additionally, the potential of meadows to advance climate mitigation and adaption have become central questions with evidence suggesting healthy meadows serve as carbon sinks as well as storing relatively more carbon relative to other ecosystem types.

More Meadows Restoration

Sierra meadows add resiliency to the hydrologic and ecological processes that sustain the headwaters of major California water sources. Horse Meadow was the top choice among 76 Sierra meadows originally screened, and 10 meadows subsequently selected as having high restoration potential in Sequoia National Forest. Horse Meadow restoration, funded by Kern Community Foundation and CDFW, will improve habitat for Kern River Rainbow Trout in the Kern River watershed. A restoration design for Horse Meadow was advanced to 65% by Plumas Corp and surveys completed for future NEPA work in 2020. Successful restoration will restore a more natural hydrology, remove incision, and prevent cattle from degrading the banks. Horse Meadow was also the designated site to pilot the SM-WRAMP protocols in 2020, leading to the completion of the protocols and associated guidance document in 2021. These protocols will be used throughout the Sierra to standardize monitoring, data acquisition, and reporting on meadows.

Like the mountain snowpack that Californians depend on for year-round water, healthy meadows store water and release it gradually.

Aspen

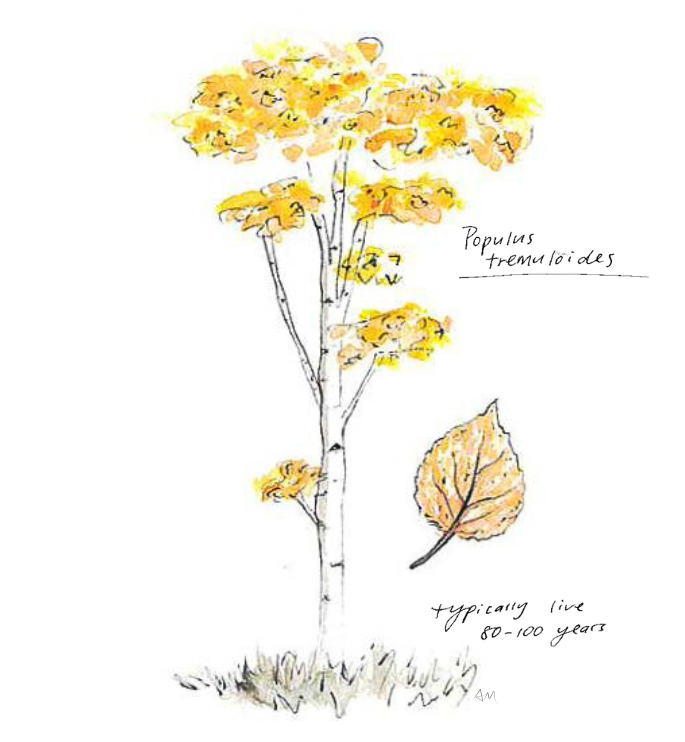

Over the last century of fire suppression, conifers have slowly encroached in aspen stands. Aspen trees require both abundant sunlight and soil moisture, and conifers introduce shading and compete for soil water, which threatens aspen survival. In addition to requiring sun, aspen stands thrive with fire. This is because a stand of aspen trees can often make up a single organism, all stemming from the same extensive underground root system. In this case, each tree in a stand is a genetic clone of the others, whereas other aspen stands may consist of several or more clones. Individual aspen trees may live to 120 to 150 years in age, but eventually they die off, even though the aspen clone may live for thousands of years or longer.

Aspen trees have thin bark which means in hot-temperature fires many are “killed” but the root systems are left intact and healthy underground, ready to sprout new shoots. When a fire comes through it stimulates new shoots to sprout out of those roots, producing aspen stems that eventually grow into a healthy, young aspen forest. According to the USDA “as many as 50,000 to 100,000 suckers can sprout and grow on a single acre after a fire.” In addition to sprouting, fire may promote aspen seed production and seedling establishment, because aspen seeds require bare and moist mineral soil for germination, and young aspen seedlings require ample sunlight and soil moisture to grow quickly into young trees. Without fire, aspen trees eventually die, and with fewer and weaker sprouts and seedlings available to grow into a new healthy stand.

Compared to conifers, aspen trees support ecosystems with a much richer diversity of species of plants and animals, making them a keystone species and a high priority for restoration.

“We hope that some of this mechanical treatment as well as burning piles within the aspen stands, will stimulate new aspen growth,” Scanlon said. “It’s a tricky spot to burn because it’s so close to infrastructure so we are hoping that even just with that work being done this will stimulate their roots to reproduce more strongly.”

Compared to conifers, aspen trees support ecosystems with a much richer diversity of species of plants and animals, making them a keystone species and a high priority for restoration.

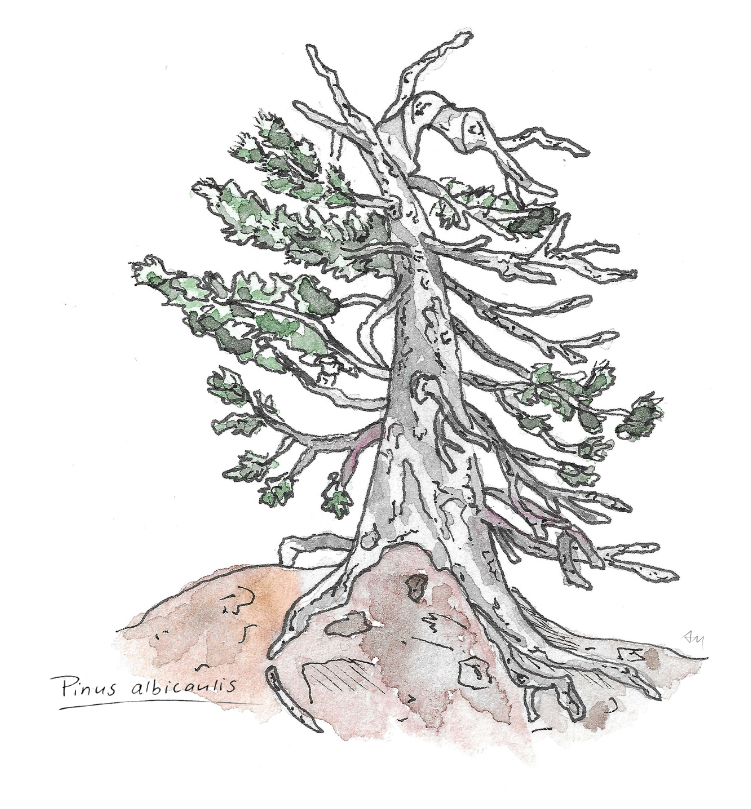

Whitebark Pines

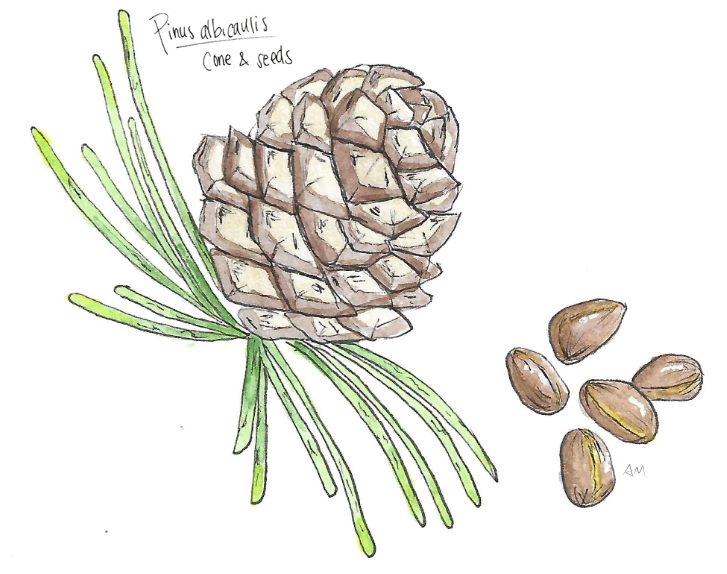

Another keystone species, whitebark pines were recently listed under the federal Endangered Species Act. Whitebark pines provide all kinds of ecosystem benefits including increased biodiversity, carbon sequestration, snowpack retention, and watershed stability.

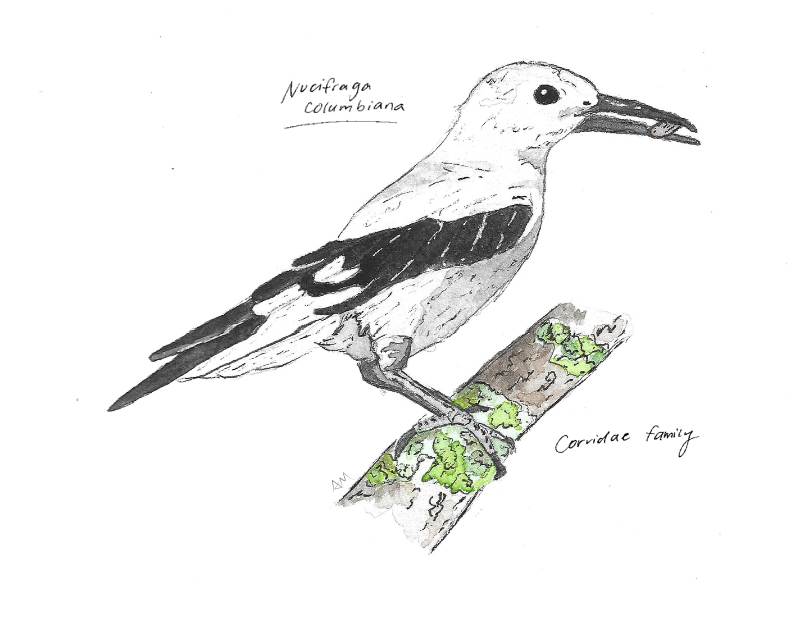

They provide nest sites and habitat for wildlife. Their seeds are packed with high nutritional content making them a major food source for many wildlife from Clark’s Nutcrackers to Douglas squirrels to bears. In the context of the larger food web, some of those carbon and nitrogen sources from the seeds will eventually end up in streams and usable for fish.

In higher elevation alpine and subalpine environments, whitebark pines provide shading for snow to melt slower, helping with snowpack retention over time. “Having those whitebark pines in our mountains is really important for providing a more sustainable flow of water delivery to downstream users,” explained Marc Meyer, Southern Sierra Province Ecologist with the Inyo National Forest.

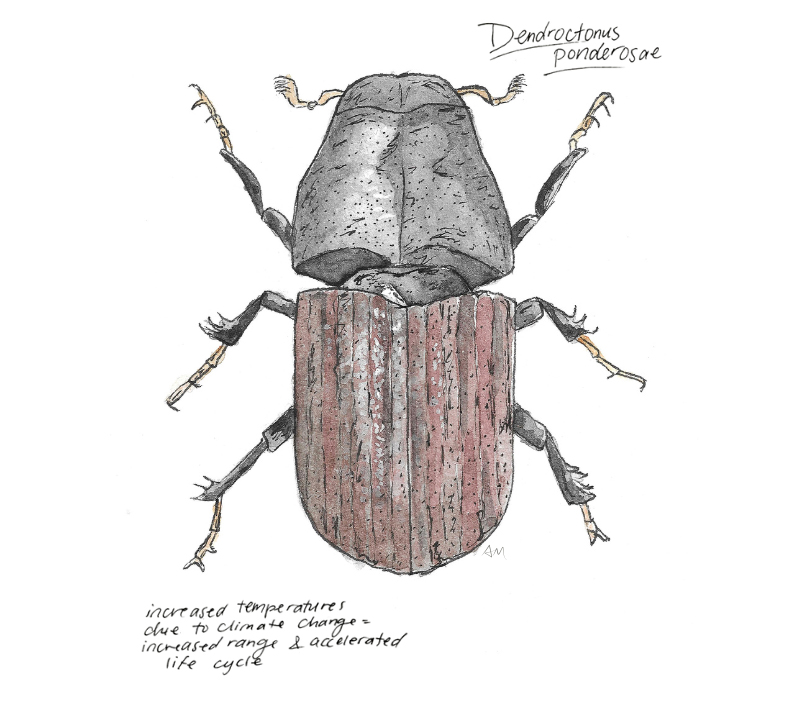

But these important trees are under attack. Pathogens like white pine blister rust, warming temperatures, decreased water availability, and attacks by pine beetles all threaten whitebark pines. Much of this is climate change driven. As temperatures continue to rise, there is less water in the soil, more water stress on trees, more pine beetle activity, and higher mortality in trees.

By selectively thinning the forest on June Mountain, this makes the trees more resilient to fighting off beetles. With more water available in the soil, trees are healthier and more capable of defending themselves by pushing sap back towards the beetles – which traps them or prevents them from entering the tree. Since thinned stands are less susceptible to bark beetle attack, individual whitebark pine trees in the stand will be less attractive to other bark beetles in the area, further improving the health of the stand. Moreover, thinning promotes the growth and survival of young whitebark pine seedlings and saplings that are important for producing the next generation of whitebark pine trees.

There are some signs of early success on the mountain. “Beetle activity on the mountain has been reduced in those areas that have been treated. But there’s still a lot of areas on June Mountain that still need that same treatment,” Scanlon said.

Forest Health Units

In the forest health units, fuels reduction is the goal. Trees up to 20 inches in diameter are thinned and piled within those units or removed from the unit for public fuelwood collection. This fuels reduction work will reduce fire intensity if a fire did occur there, allowing firefighters to control the fire more easily and giving the trees a better chance at survival. Creating an environment for fire to burn in a healthy manner would also help create a buffer zone adjacent to infrastructure.

“One of the greatest challenges of this project has been to figure out what to do with all of the downed trees,” said Julie Brown with Mammoth Resorts which owns June Mountain Ski Resort.

Much of the wood is hauled off the mountain but getting it down is no easy feat. The access road up June Mountain is about two miles long with a large hairpin turn, and it is so steep that it has a pitch of up to 14 degrees in some places.

Much of the wood is hauled off the mountain but getting it down is no easy feat.

Because some units themselves are difficult to access with no adjacent roads or ski runs, some wood is left in place and burned or chipped.

Because some units themselves are difficult to access with no adjacent roads or ski runs, some wood is left in place and burned or chipped. But not much biomass will be left up on the mountain.

“The idea is to get rid of as much of it as possible whether it’s hauled, burned, or chipped,” Dodds said.

Visiting June Mountain?

If you’re hitting the slopes this winter, check out the changes from this work! Julie Brown explains, “From the top of June Mountain (top of J7), if you look east to the top of Rainbow Ridge (the top of J4 and J6), you can compare the forest within our boundary area and the forest outside our boundary. The difference in the two areas is remarkable, with our forest thinned of dead tree mortality and the dense mortality you can see in the Ansel Adams Wilderness.”

Off-season at June Mountain Ski Resort.

The Community Below the Mountain

A healthier forest on June Mountain doesn’t just benefit fish — it also benefits other wildlife, people who live nearby, and those who visit the area. Closer to the town of June Lake, home to a population of about 400 people and nestled beneath the mountain, thinning the forest is important to reduce the risk of a catastrophic fire threatening the town.

“As the land managers for these public lands, one of the biggest priorities for Inyo National Forest is to make sure these communities are safe places to live and are resilient to forest fires,” Scanlon explained. “June Mountain is strategically placed.”

Winds tend to originate from the southwest during strong events. If a forest fire were to start in the wilderness behind June Mountain, the winds would naturally blow it southwest which would push the fire out of the wilderness into June Mountain and then down into the town of June Lake. This makes June Mountain a critical area to treat to ensure healthier forests that are more resilient to fire and that can slow the fire down in speed and intensity before it can reach the June Lake community.

The community of June Lake, and others, also benefit from a public firewood collection site from wood hauled down from the mountain. Anyone with an appropriate permit can stop by and collect wood for their personal use.

Kirstie Butler, a Fire Prevention Technician (patrol) with Inyo National Forest, has lived in June Lake for ten years, and she was able to participate in the public wood collection. As both a community member and a member of the project team, Butler sees the full picture of this project for June Mountain.

“Unhealthy trees and too thick of a stand density is making the rest of the flora and fauna suffer,” Butler said. “This project is long overdue, and I’m stoked that it’s happening. In the future, I want to see even more acres treated.”

The community of June Lake, and others, also benefit from a public firewood collection site from wood hauled down from the mountain.

From the Mountain to the Valley

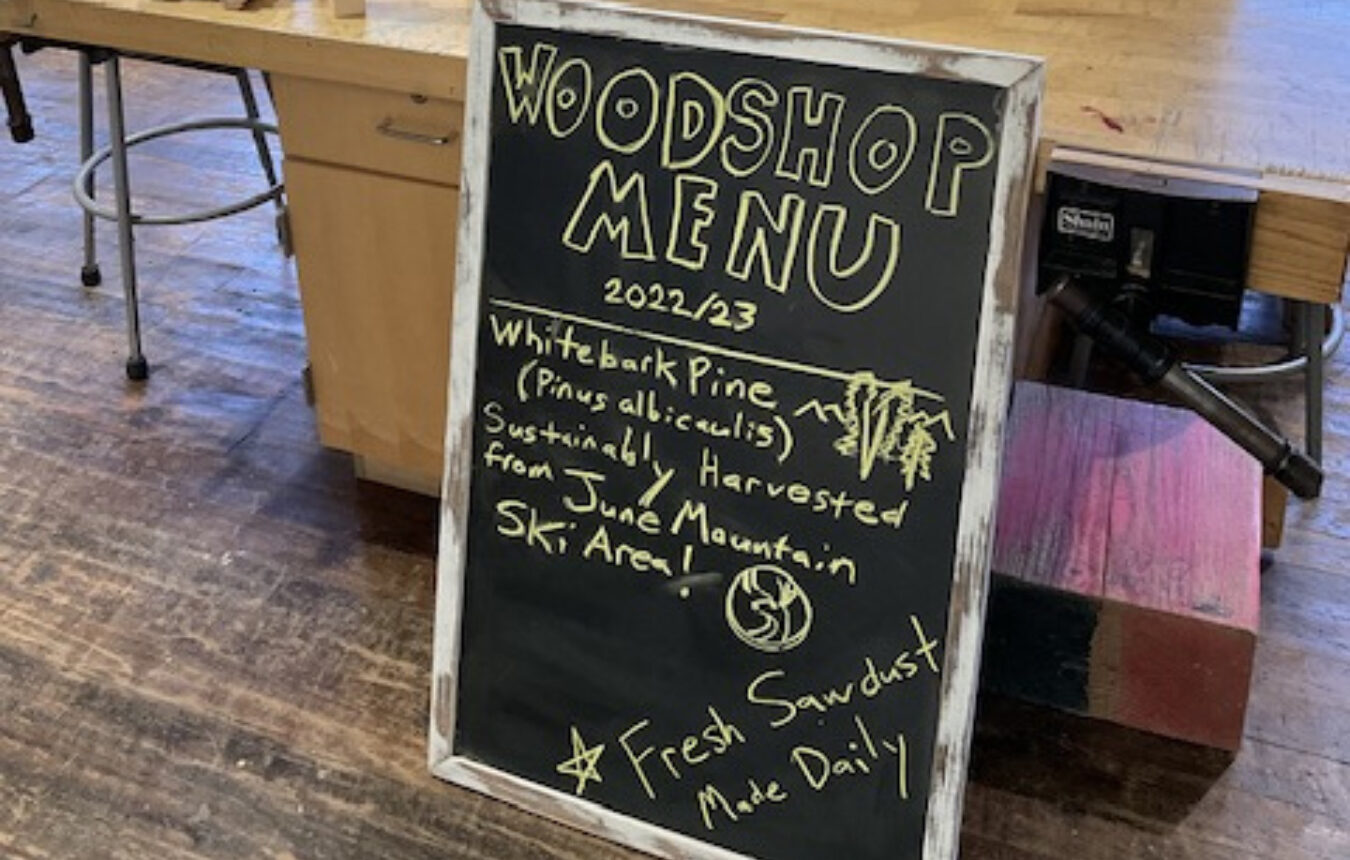

Ryan Lang learned to ski on June Mountain. When he was young, his uncle had a cabin where he and his family would spend time. Today, as a woodshop teacher at Ojai Valley School, he is always on the lookout for down or dead logs. On one of his trips up to June Mountain, he came across the public wood collection site with trees thinned from the mountain.

“Obviously, I saw that pile of ginormous, dry, perfectly seasoned, beautiful, blue-stained pine and went, ‘well that's coming home with me!’” Lang said.

He loaded it into his truck and brought it back with him to the school’s 120-year-old woodshop. Before using the wood, Lang and his students, aged pre-K through eighth grade, always look up the tree species to learn more about it and where it came from. Then, the students are involved in the milling before they craft it into all sorts of objects.

Lang grew up in the Matilija Canyon, under the shadow of Matilija Dam. Many of the cabins and houses built in the valley years before, including his own, were constructed before the dam existed because of the abundant steelhead that swam through the canyon. When the dam came in, the whole ecosystem changed.

Matilija Dam Removal

Matilija Dam, located in the Ventura River watershed on Matilija Creek north of Ojai, is a concrete arch dam built in 1947. It was originally designed for water storage and flood control, but the reservoir behind Matilija Dam is nearly completely clogged with sediment, significantly reducing storage capacity to the point that the dam is rendered non-functional. With no fish ladder or bypass structure present, it is a complete barrier to the migration of endangered Southern California steelhead. The dam also causes degraded water quality, an altered flow system, and a disorder to the sediment flows towards the lower watershed, estuary, and beaches, which need sediment to replenish themselves. Spanning 20 years of effort, a broad coalition of community groups and resource agencies including CalTrout have advocated for Matilija Dam removal, working together to develop a comprehensive strategy to restore the Ventura River. With no uncertainty, Matilija Dam is set to come down. Removing Matilija Dam will restore a free-flowing river from the headwaters to the ocean, re-establish access for steelhead trout to required habitat, revitalize a healthy, native ecosystem, and expand opportunities for outdoor recreation.

Ojai Valley School students tour Matilija Dam

“Seeing how important it is to restore these ecosystems is something that I have to share with my students. I have to show them what they can do and what they can vote on when the time comes to repair some of the mistakes that we made,” he said.

Improving Forest Health for Lahontan Cutthroat Trout Protection

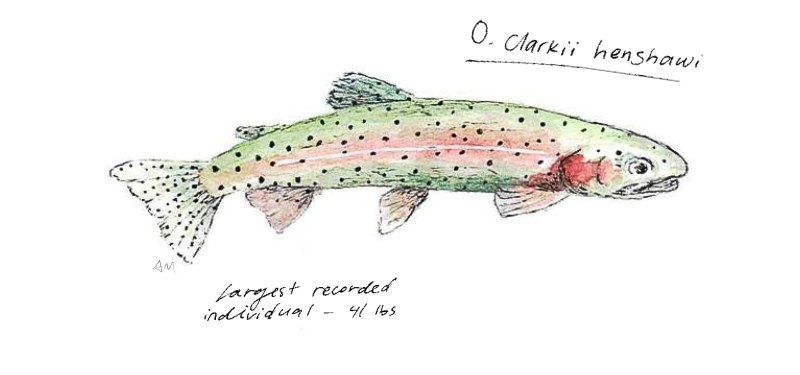

Just an hour north of June Mountain, in Mono County near the small town of Bridgeport, CalTrout is implementing another forest health project at By-Day Creek Ecological Reserve, which supports native, federally-threatened Lahontan cutthroat trout.

Lahontan cutthroat trout were once widespread across high-elevation mountain streams and lakes in California and Nevada including Lake Tahoe. Today, they are much harder to find. Approximately 95% of the species has been extirpated from their historic habitat in California largely due to introduction of non-native trout species and habitat alterations by human land use activity.

Protecting and maintaining the Lahontan cutthroat trout population in By-Day Creek is crucial to support recovery of the species. The By-Day Creek Forest Health Project is a collaborative project between CalTrout and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) to implement thinning of overly-dense white fir forest understory. This will improve forest health and reduce the threat of catastrophic wildfire to protect Lahontan cutthroat trout populations.

Implementation began in September 2023 in partnership with contractor California Reforestation. By thinning the forest around the creek and adjacent fire road, this project helps protect native fish from catastrophic fire events. Thinning will also create a buffer along the road to allow better access for fire suppression apparatus and personnel to work in the event of a wildfire.

“Instead of spreading efforts across the whole reserve, this project focuses in on a key corridor within it,” Dodds explained. “We are creating a buffer zone along the creek and along the fire road.”

In Silver Creek, a tributary to the West Walker River, CalTrout works with CDFW to remove non-native brook trout to protect native trout.

How else is CalTrout working to protect Lahontan cutthroat trout populations?

In the Walker Basin, part of the Lahontan cutthroat trout’s (LCT) native range, CalTrout is partnering on restoration projects to eliminate non-native trout populations from the system and help maintain these LCT populations. In Silver Creek, a tributary to the West Walker River, CalTrout works with CDFW to remove non-native brook trout. Brook trout are native to the East Coast, but on the West Coast they are a prolific non-native species that threatens the health of native fish population. Next year, CalTrout staff will expand work in the Walker Basin to Slinkard Creek where non-native fish removal efforts will continue.“I see a future in which we have healthy forests that support healthy watersheds and in turn healthy communities on June Mountain and beyond,” Dodds said. “I’m honored that CalTrout gets to play a role in making that future possible.”

Illustrations by Alix Martin.