Eel River Forum discusses Pikeminnow

*This article was originally published on the Redheaded Blackbelt on April 11, 2019

Young Pikeminnow [Photo from Eel River Recovery Project]

Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations considers Pikeminnow to be the most significant obstacle to salmon recovery in the Eel River. Reducing mature Pikeminnow population by 10-20% may decrease the salmonid kill rate by half. Yet in the 40 years since Pikeminnow entered the Eel River watershed, no one has found a reliable method to remove them.

To address the Pikeminnow conundrum, CalTrout’s Eel River Forum held a day long seminar on Pikeminnow science March 27th at Fortuna’s River Lodge Conference Center. Nine Pikeminnow experts presented the information they know, and the studies they are developing to learn more, to a packed room of river biologists and restorationists over a 4 hour period.

While Pikeminnow have been in the Eel River since the 1970’s, Josh Fuller, the NMFS Lead Biologist regulating the environmental impacts of the Potter Valley Project, said NMFS is still trying to develop an effective Adaptive Management Plan and, “I am just so excited that CalTrout is putting this on. We need help right now tackling this issue both in the [Potter Valley] Project Area and throughout the watershed.”

Pikeminnow are an invasive, predatory fish species in the Eel River, but Pikeminnow are native to other salmon bearing rivers of California such as the Sacramento and Russian Rivers. They are incredibly smart in the fish world. Several speakers at the forum report that they have tracked them sneaking out of deep pools where they are protected, to feed in the shallow areas only at night. They also appear to have the ability to learn to recognize fishing lures and to move away from them.

Urban legend says that Pikeminnow came directly up the Potter Valley Project diversion from the Russian River into Lake Pillsbury, but that isn’t accurate. Dr. Brett Harvey of the U.S. Forest Service’s Redwood Sciences Laboratory said this line of Pikeminnow came from Clear Lake and that ten individual fish were likely brought into Lake Pillsbury by one angler.

Pikeminnow were first seen in the Eel River watershed in 1979 and, from those ten fish, were pervasive throughout the watershed by 1986. The only fork of the Eel River not completely overwhelmed by them is the North Fork and BLM Biologist Zane Ruddy told the room that the Pikeminnow may be colonizing there right now.He said there are currently at least three year-classes of Pikeminnow present in the North Fork. Ruddy said, “I hope to instill a sense of urgency in the crowd….now is the time to strike because they are in low abundance.”

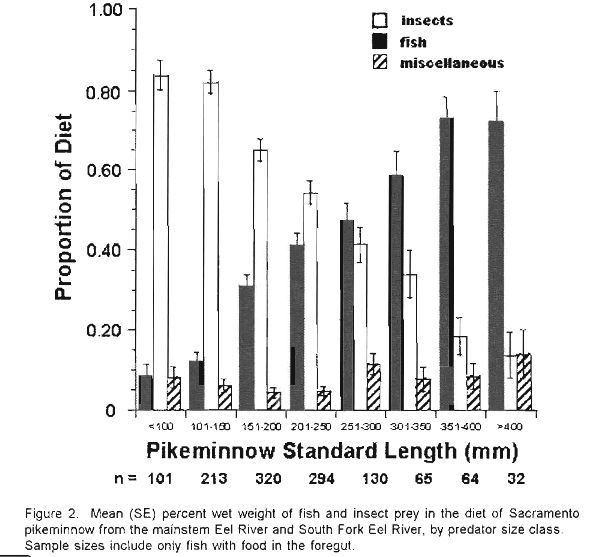

[Graph from:Nakamoto, R. J. and B. C. Harvey. 2003. Spatial, seasonal, and size-dependent variation in the diet of Sacramento pikeminnow in the Eel River, northwestern California. California Fish and Game 89(1): 30-45]

The graph above reflects the fact that Pikeminnow eat a wide variety of species and that their diet turns to a larger and larger percentage of fish as they increase in size.

However, even as very tiny fish, they are a threat to salmonids both by predation and competition. Pikeminnow eat such a wide variety of food types that it is suspected that the smallest fish will prey upon the redds before they hatch. Furthermore, smaller Pikeminnow compete with juvenile salmonids for their food sources before they grow large enough to consume the salmonids directly.

Studies show Pikeminnow’s advantage gains when the temperatures rise. Describing a study evaluating the impacts on competition, Dr. Harvey said, “At about 17 C the Pikeminnow are invisible to the Steelhead, …but when you jack up the temperature about 4 or 5 degrees C, then its a different game and the Pikeminnow are a direct competitor to the Steelhead. In fact, it was kind of an ‘adding insult to injury’ situation because the performance of the Pikeminnow in this setting was kind of like that goofy person who won’t receive social cues. …The Steelhead were busy trying to defend their territory as they do; trying to be rude to their neighbors as they always are, and the pikeminnow were [oblivious].” He went on to say that at that temperature adding a Pikeminnow had the same level of competition as adding more Steelhead. They were in direct competition for food.

Another study reveals that in winter, it appears the Pikeminnow retreat from the headlands and return to them later in wetter years and ealier in drought years according to Philip Georgakakos a Dorctoral student from UC Berkeley. Georgakakos said he finds June is the month with the largest difference between wet and dry years in terms of the respite salmonids receive from Pikeminnow predation and competition in the headwaters of the South Fork at his study area in the Angelo Reserve west of Laytonville.

Although there has been little progress in controlling Pikeminnow over the 40 years since their arrival, solutions are being pursued. In the majority of the watershed, Pat Higgins of the Eel River Recovery Project hypothesizes that River Otters are the primary predator keeping the Pikeminnow population from exploding and completely decimating the salmonids. And around Lake Pillsbury where the habitat allows Pikeminnow to thrive, the community holds an annual sport reward Pikeminnow Derby. In the derby, every entrant over 12 year of age, pays an entry fee to compete. That forms the prize pool which is parsed out to the anglers who return with the largest fish, the smallest fish and the most fish. According to Higgins, the last derby may have removed 600 pounds of Pikeminnow from Lake Pillsbury.

The derby model is the preferred model in the Columbia River where the Bonneville Power Administration pays out nearly $4 million a year to reward anglers for removing Northern Pikeminnow. A few anglers in that area make their living on that opportunity according to the program’s director Steve Williams. The Northern Pikeminnow is native to the Columbia River, Williams pointed out, so there is no effort to eradicate the species in that watershed.

In the Eel River more solutions are being explored. Abel Brumo of Stillwater Sciences has been working alongside the Wiyot Tribe toward the Tribe’s goal of returning the river they historically named Wiyot to its former state of abundance–which is the meaning of the word Wiyot. Brumo and the Tribe will be working this summer to discern which Pikeminnow removal method is the most cost effective. Brumo says they will be evaluating boat based electrofishing, nighttime dives with nets, and baited fish traps. They will look at which method makes the most sense for both the money and the time it takes to remove the predatory fish.

Meanwhile, Pat Higgins of the Eel River Recovery Project (ERRP) has hopes of cutting the number of female spawners in the upper South Fork of the Eel significantly enough to increase juvenile returns to the ocean significantly. ERRP has applied for a Scientific Collecting Permit from CDFW to gain permission to have trained fish science experts who can easily recognize fish species from a distance work in the deep pools of the South Fork of the Eel River in the refugia area between Rattlesnake summit downstream to French’s Camp. The proposal is for the volunteers to spear the Pikeminnow larger than 10 inches long in the pools. According to Dr. Harvey each female can produce 15,000 eggs in her lifetime. Therefore, Higgins hypothesized that because the females are the largest fish, killing them has a few benefits. Killing them will reduce current predation of the most mature salmonids, and it could reduce future Pikeminnow population by at least half. California Deparment of Fish and Wildlife has expressed a preference for electofishing for the Pikeminnow over spearfishing because if other species are present, they are not killed accidentally. However, Higgins says electrofishing is ineffective in these deep pools where these larger Pikeminnow are hiding during the day. CDFW has 12 weeks to review the application which was recently submitted.

The most experimental proposal came from Dr. Buchheister of HSU’s Fisheries Biology Department who reported to the forum from Arcata by telephone. Buchheister explained the Trojan Y project which is used in fish farming. Buchheister is working on with his colleague Dr. Rafael Cuevas Uribe. The Trojan Y uses genetic modification, however no extraspecies genetic information is added, to cause almost all offspring to be YY male instead of XY male. In fish farming it is widely practiced, according to Dr. Uribe, to keep the farmed fish from expending energy on reproduction. In the case of Pikeminnow it is being considered because it will cause the population of the target species to crash because not enough females will be produced. To date, there has only been one trial for species control on invasive Brown Trout in Idaho. Uribe said that depending on the number of YY males stocked into the watershed, the Pikeminnow might be expected to go extinct within 10 to 20 years after the YY males were introduced.