Field Note: Creek Geeking with California Academy of Science Interns

A Field Note from Walker Creek Ranch, Marin County

by Will Ware, CalTrout Bay Area Project Coordinator

November 2023

Sparkling sunlight mixed with shadowed hues in a fluid mosaic over Walker Creek as I followed Alex Johanson, CalTrout-UC Davis Graduate Fellow, on a spawning survey. These surveys help us estimate coho salmon reproduction in the creek, and they are also a great excuse to explore new places outside. While searching for coho salmon nests, called redds, Alex saw a young-of-year steelhead swim downstream. Seeing nothing, I imagined a metallic flash as the young fish swam downstream on its quest to grow, venture into the ocean, and return back to this reach of streamflow. Although we did not find any salmon, we wanted the day to be memorable for a group of high school “Careers in Science” interns arriving from the California Academy of Sciences. Alex and I agreed that our own unique career paths percolated from multiple moments that connected in retrospect, so we hoped to connect a dot for some of these young students.

“Why care about science?” I asked the group of high school sophomores and juniors seated at the outdoor amphitheater. Attention naturally meandered in a stream of consciousness as the interns took in their surroundings before concentration returned to the question. Several shared that science allowed them to understand how things work. Focus ebbed when a gray fox family wandered around us so I asked the interns to share their observations on these typically shy, nocturnal canids. After admiring the long, fluffy tails, interns questioned if the foxes were adapting as they search for scraps in broad daylight. Our focus flowed to fish as we discussed coho salmon using their paddle-shaped tails like shovels to dig and bury their eggs in redds.

“Why care about coho salmon and steelhead?” I posed another question. We reflected on what it actually meant when interns said that these fish are culturally important, a “keystone species,” and “watershed indicators.” The closure of salmon fishing along California’s coast and in several of its rivers reduces income for commercial fishers, challenges businesses that support recreational fishing opportunities, and thwarts California Indigenous peoples’ connections to their resources. Falling salmon populations also reshape marine ecosystems as species that rely on them like southern resident orcas also fall. Coincidence? “I think not” students joked, quoting Kim Possible and providing hope that I was not yet fully out of touch with Gen Z. Remove the keystone from the equation and everything crumbles. In freshwater, salmon populations indicate the quantity and quality of water that sheds off landscapes. This is why salmonids are beacons of hope for restored watersheds along the West Coast such as when they return past decommissioned dams and up urban streams.

Alex gathered everyone around a large boulder that is fittingly called “The Grinding Rock.” The Coast Miwok people ground acorns within stone pits, and the resulting flour was a dietary staple that was paired with salmon captured from Walker Creek. Alex reflected on how people are using Traditional Ecological Knowledge as a tool to restore human environmental impacts and cultural connections to nature. This reconciliation ecology strives to support society and biodiversity. Several interns shared that they wanted to close gaps between built and natural environments to support conservation as ornithologists, geologists, epidemiologists, and medical professionals. Most lived in San Francisco and had limited access to open spaces but their connection to nature was rooted like rooftop gardens. These connections bore fruit as a desire to steward nature with urban planning and increase access to natural spaces.

Down by the creek, we donned rubber boots and wielded dip nets to stir aquatic insects from the streambed. My net traced my steps as I dislodged leaf litter and gravel to uncover a cache of fish food, orbugs,before the interns began their search. We learned together as we used magnifying enclosures and a field guide to identify the nymphs of mayflies, stoneflies, and dragonflies alongside scuds and caddisfly larva. The interns also enjoyed watching water beetles, water striders, and caterpillars before they brought me several spiders. After looking eye-to-all-eight-eyes, it was time to release the arthropods. As the aquatic ones floated downstream, I posited that insects in the stream channel did not provide enough food for coho salmon and steelhead to grow large. The small fry likely grow into parr before they swim down to Tomales Bay where they can feed on more abundant invertebrates just as they do in other coastal watersheds.

Life Cycles

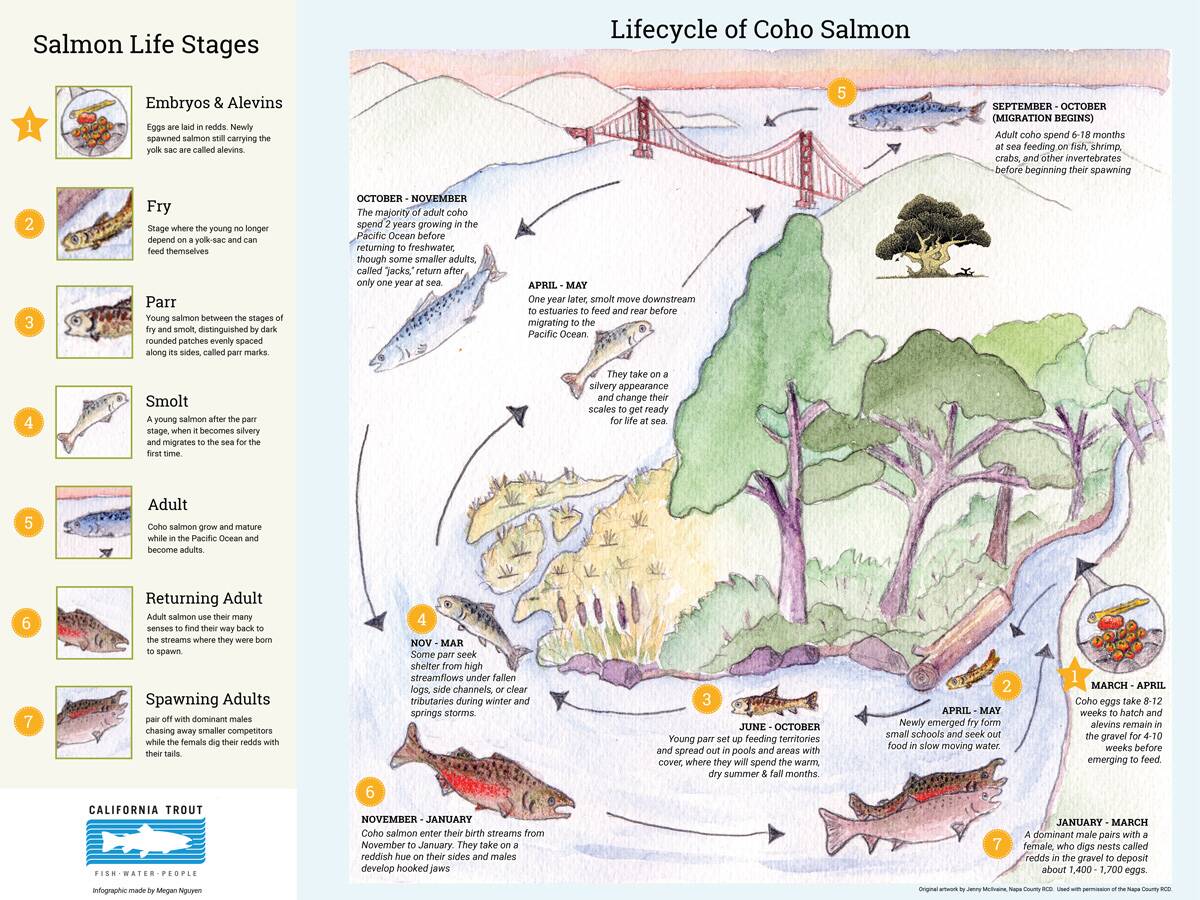

Coho salmon progress through multiple life stages as they go to the ocean and return back after two years. Alex explained that although female coho salmon lay up to 1700 eggs, most will not survive. The odds for juvenile salmonids are also not in their favor and slowly increases as they reach adulthood. Those that outlast disease, environmental conditions, and genetic flaws grow in a perpetual Hunger Games as they avoid aquatic and oceanic predators while hunting for their own food.

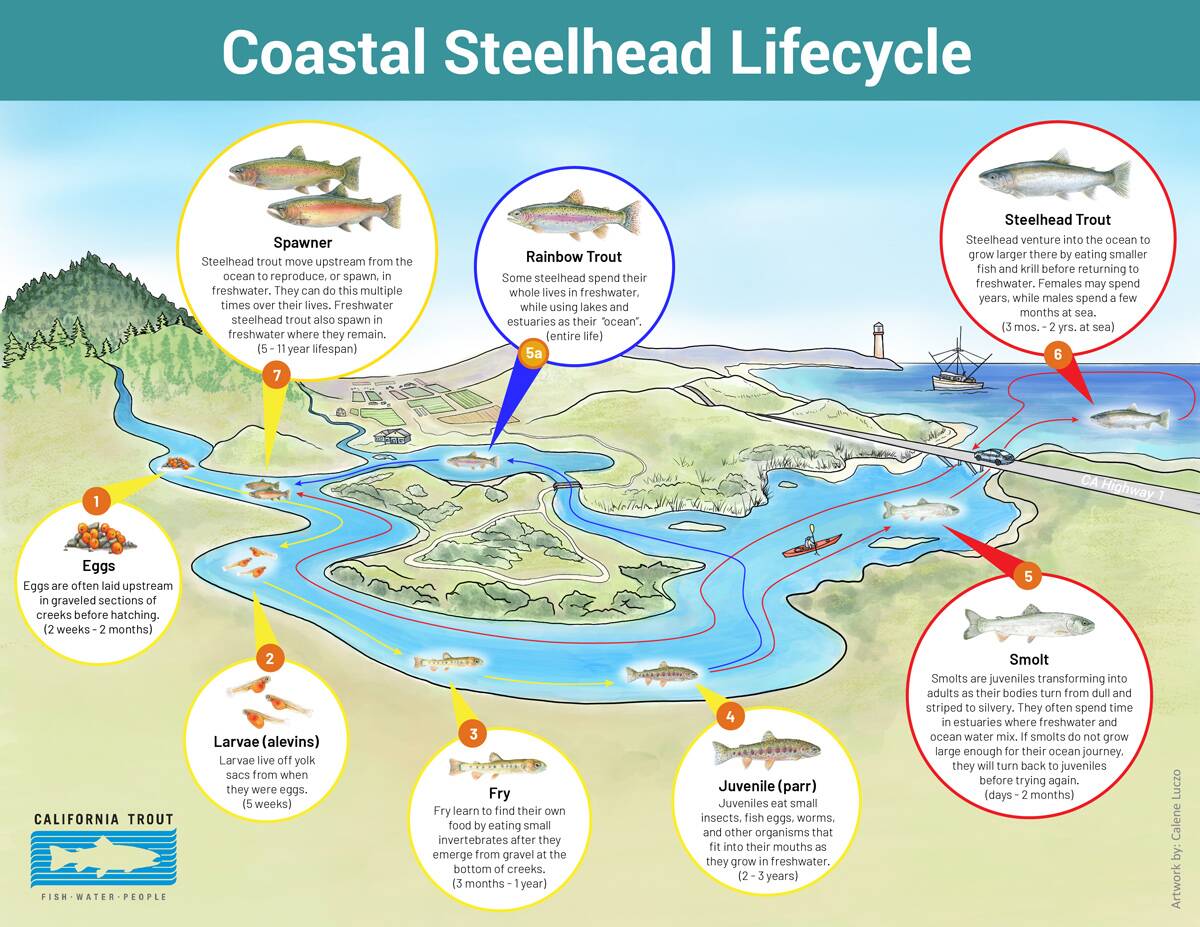

Steelhead life cycles vary between individuals as they approach adulthood. Parr are like teenagers that begin venturing downstream from where they hatched to find larger prey in either the lower reaches of their streams or estuaries. Smolts are like young adults that go to estuaries to prepare to leave their home streams for the ocean. They can revert back to parr when they are not yet ready for the ocean and they return back upstream, like “boomerang kids,” before they later go out to sea as smolts. Adults spend varying amounts of time at sea, from males called “jacks” that may stay out for a few months to females that can stay out for years. Once adults return to freshwater, they spawn and can continue living before going back to sea to spawn again another year.

As the interns shared their career aspirations and interests in conservation, their unbridled ambition and energy flashed before me like steelhead moving down a free stream. It was fulfilling to hear how their diversity of backgrounds matched their prospective professions, and how their backgrounds shaped how they wanted to merge built and natural environments. As a suburban kid, nature documentaries, aquarium trips, and then time exploring nature were the springs that my conservation career still flows from after I found my way into fish ecology. I hope to see where the California Academy of Science interns go on their paths next, and I’m happy to be a resource for others who are finding their way into a conservation career.

1 Comment

What a lovely and inspiring story! I really enjoyed it.