Southern Steelhead Are Adaptive And Resilient

Southern Steelhead are Adaptive and Resilient

Southern California steelhead are statistically the most endangered native fish in America. In the early 1900s, hundreds of thousands of them returned to the rivers between San Louis Obispo and Mexico. Now, there are reportedly under a few hundred adults returning annually.

Rainbow trout historically populated all coastal streams of southern California with permanent flows, as either resident or anadromous forms, or both. Today, the southern steelhead range spans over 30,000 square km (about 11,580 square miles), has over 41,500 km (25,785 miles) of mostly intermittent streams.

Thankfully, they are also one of the most adaptive and resilient fish. Southern steelhead can tolerate warmer water temperatures than their northern counterparts, up to about 25˚C (77˚F), before they seek refuge in pools with cool seeps. In southern California, these fish are subjected to huge variances year to year of flows, sediment loads, water temps, wildfire effects, pollution, and other negative environmental factors.

While anadromous steelhead are only sporadically present in the current population, resident Rainbow trout occupy the upper watersheds of most rivers year-round and may be responsible for maintaining steelhead runs through their offspring when streamflow conditions are favorable. Anadromous offspring from resident parents are common enough to make the protection of resident fish an integral component of Southern steelhead recovery.

Photo: Drew Farwell

The Endangered Species in Our Backyard: Our Role in Their Survival

Bearing a striking resemblance to their freshwater cousins, the Rainbow Trout, with hues of green, silver and pink, a steelhead is a remarkable fish. Steelhead are anadromous, meaning they are born in freshwater, spend part of their adult lives in the ocean, and return to the rivers and streams where they were born to lay their eggs. When they leave the rivers they are six to eight inches, and return to spawn when they are as big as ten pounds. This transformation is vital to their surrounding ecosystem because the steelhead bring back a huge amount of nutrients with them from the sea. A Southern Steelhead is unique from the steelhead you would find further north because they have adapted to the arid climate of Southern California. They have learned to survive in warmer water and to persist through long periods without substantial water flow, essentially waiting it out in small pools in the highest reaches of the watershed until the rains come.

According to Russell Marlow, the South Coast Project Manager for CalTrout, “These fish are insanely adaptive and resilient.”

Despite all odds the Southern Steelhead refuses to give up. They keep coming back to the same river where they were born and are turned away time and time again by man-made obstacles. Their home waters have become polluted, blocked by dams and infiltrated by invasive species. Human activity has made their homes very inhospitable. The Southern Steelhead are survivors, like steel, they have bent but not broken. The Santa Ynez River, in our own backyard, is imperative to their chances of being taken off the list of critically endangered species

The Santa Ynez River was historically the most productive steelhead river south of San Francisco. The Chumash Tribe celebrated their abundance and relied on them as a major source of food in the winter. Tens of thousands of Southern Steelhead Salmon would make the 65 mile trip up the Santa Ynez River from Surf Beach to their spawning grounds above Red Rock. As Santa Barbara County grew larger and needed a reliable water source, Gibraltar Dam (1920) and Bradbury Dam (1953) were built.

“Bradbury Dam was built in an area of The Santa Ynez River that cut off two-thirds of the Southern Steelheads suitable spawning ground.”—Marlow

Bradbury Dam has had a drastic effect on the steelhead. The last time the Santa Ynez breached through to the ocean, only 200 salmon were counted returning to their ancestral river. That is a 99 percent decline in 70 years. According to data from California Trout, the leading fish conservation group in California, “Southern Steelhead populations are in danger of extinction within the next 25-50 years.” The last large run of Steelhead occurred in 1949. Only 71 years ago.

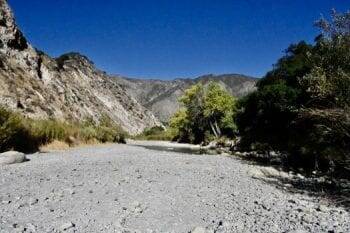

The Santa Ynez River. Photo Nathan Irwin

The Santa Ynez River lies in an arid landscape, remaining mostly dry and flowing primarily underground for years at a time. If you don’t keep your eyes peeled on the drive from Santa Barbara to Santa Ynez you might not know that there is a river there at all. When it rains, Lake Cachuma, Gibraltar, and Jameson Reservoir all receive their water first. After the reservoirs fill up and Bradbury finally releases water into the Santa Ynez River below, the groundwater gets replenished. The water that remains is portioned out to private landowners along the watershed, essentially sucking a dry riverbed even drier. These man-made water systems along The Santa Ynez River Watershed need to fill up before the river can reconnect with the ocean and allow for a passageway for the salmon to return home. According to a 2016 National Marine Fisheries Service report, “Bradbury Dam, which creates Cachuma Reservoir, is the largest barrier on the Santa Ynez River and operations restrict flows necessary to support suitable steelhead habitat.” These barriers are making it impossible for the steelhead to make it back to where they spawn.

Bradbury Dam and Lake Cachuma. Photo Eric Foote

The dams along the Santa Ynez River do not have any type of fish passage. The steelhead are stranded behind walls of cement; blocking them from their spawning grounds. Our county built Bradbury Dam with the knowledge that at least half of the fish in the Santa Ynez River would die. The last remaining anadromous Southern Steelhead in The Santa Ynez River are kept alive year-round in Hilton Creek by the federally funded Cachuma Operations Maintenance Board. This project involves a large pump system that shuttles water from Lake Cachuma into a small tributary below Bradbury Dam, where there are hundreds of Southern Steelhead. This is a temporary fix for a much larger problem, yet it is providing the remaining fish a chance to survive for now. Ultimately these stranded fish need a way to get to the other side of the dam to complete their life cycle. There are plans to help these fish achieve this goal through methods like trucking the fish into the higher reaches of the river and then back again during high flows, building a new channel for the Santa Ynez River that bypasses Bradbury Dam altogether, or removing the barriers completely.

“California Department of Fish and Wildlife did a population surveys and estimates before the Bradbury dam was built, concluding that there would be at least a 50 percent die off of fish if they were built without any fish passage.”—Marlow

The mistakes and oversights that were made in the past need to be rectified by rethinking the way we provide water for our county. The days of large salmon runs in the river are gone because of the systems for water delivery and water control that were built 100 years ago. Santa Barbara County needs to rethink the antiquated plan of one large reservoir in the middle of the most productive Southern Steelhead river south of San Francisco. The disappearance of the keystone species of the Santa Ynez Valley is a giant red flag to the health of the entire ecosystem in the Santa Ynez Valley and Santa Barbara County. The remaining fish are shouting at all of us to do something before it’s too late. These fish are the link between the health of the rivers and the land. They are the original locals of Santa Barbara County and they need our help.

With the continuing growth of Santa Barbara County and its unceasing need for water, the Southern Steelhead in the Santa Ynez River are on life support. Our population in Santa Barbara County continues to grow, with our latest census counting 430 thousand of us living here today. According to census.gov, our population was 90 thousand when Bradbury Dam was built. With largely the same water infrastructure and new growth on the horizon, how is this sustainable?

Taking Action to Create Change

In a recent conversation with Marine Ecologist Dr. Dawn Murray, we discussed how people can help these endangered fish. She told me that in order to have our voices heard we should, “write letters to your Congresspeople and Senate representatives – write and tell them about this majestic fish species that is so key in restoring our habitats.” This is the first step in creating a better future for these fish.

Dr. Murray expresses my feelings about these fish and our role in protecting them in stating, “restoration of species whose populations and habitats were affected by humans, seems like the least we can do as conscious beings sharing this planet.”

We are interconnected with these fish. They represent the overall health of our environment in Santa Barbara County. Marlow emphasizes Murray’s statement by saying that the, “Southern Steelhead are keystone species, so they go—we all go. The ecologic processes that maintain their habitats are the same which create irreplaceable at scale ecosystem services for our region. It isn’t the least we can do, it is what we must do.”

Organizations that Support the Southern Steelhead

There are organizations that we can support who are fighting to save the Southern Steelhead. CalTrout is one of these organizations that are focused on a, “headwaters-to-ocean approach that focuses on restoring critical habitat, recovering degraded estuaries and removing fish barriers that block fish passage.” If you would like to get involved and donate to their cause you can find out more here: https://caltrout.org. The Environmental Defense Center is committed to helping these fish, “through education, advocacy, and legal action.” To learn more about the EDC and to donate to their cause of protecting our environment, you can visit: https://www.environmentaldefensecenter.org/. If we provide our support to these groups, we can make a big impact on whether or not the Southern Steelhead survive.

Without public understanding of their perilous status and bountiful past, the Southern Steelhead could wind up lost in time. We can immediately be a part of their survival story by: taking shorter showers, brushing our teeth while the tap is turned off, using efficient washing machines and water-wise dishwashers, implementing drought tolerant properties and widespread use of recycled water, donating to local environmental groups and writing our Congresspeople. If we take action now, we can help the Santa Ynez River flow freely to the ocean like it is intended to, allowing for the Southern Steelhead to populate their ancestral river once again.

Southern Steelhead: A Story of Recovery (Storymap)

If you want the full story on Southern California steelhead−their history, why their population has declined so drastically, and what conservation groups have been and are currently doing to recover this threatened species−check out the story below made by US Fish and Wildlife Service. We’re excited, but not surprised, to see CalTrout’s Dr. Sandra Jacobson (a geneticist and avid fly fisher of 37 years) featured prominently for her incredible work leading the South Coast Steelhead Coalition. “Jacobson’s drive for success is contagious, and she is as positive as she is clear about the coalition’s goals, “we are implementing the Fisheries Service’s Recovery Plan, and their steelhead expert, Mark Capelli, provides insight as an active member of the coalition. We are committed to improving habitat and stream connectivity for steelhead. An effort of this scale takes time and people, and this group is filled with great people who are working to make a difference,” she said.”