California’s Coho Salmon On Verge of Extinction

UC Davis’ Peter Moyle has studied California’s native fish species since the 70s, and in a distressing post on the California Water Blog, he suggests less than 1% of historic Coho salmon populations remain in California’s waters:

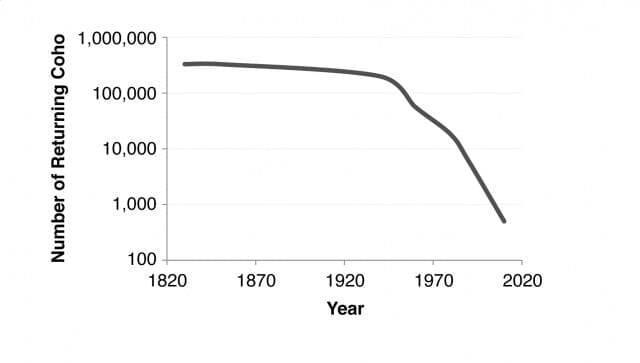

The State and Federal fish agencies were skeptical of our results, but when they did their own studies they found the situation was just as bad as we had indicated. Ultimately this led to California coho salmon being placed on the endangered species list (1996). In the past three years (2008-2010), estimates by California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) indicate somewhere between 500 and 3000 adult coho total returned each year to California streams, a 90% decline since our last study, meaning that at most 1% remain. They are virtually extinct south of San Francisco Bay. Coho numbers have continued to decline to the point where the coho recovery plan (NMFS 2007) is more of an extinction prevention plan than a plan for recovery.

Moyle also points out that populations of all Salmon in the Eel River have declined by 99% — an astonishing number.

In fact, Moyle suggests the Coho has little hope of escaping extinction in the state of California. In Part II of his informative blog post, he lays out the reasons for this precipitous decline — and what can be done about it.

In my last blog, I provided evidence that coho salmon were headed for extinction in California. Here I discuss why and what we can do about it. The over-riding cause of coho decline is 150 years of land abuse in fragile coastal watersheds. This abuse is from logging, farming, grazing, mining, urbanization, road building, and other practices that alter ecosystems, cause massive sediment delivery to the rivers, divert water, block fish migrations, and generally create environments inhospitable to coho salmon.

While these abuses are being dealt with in small ways by agencies, one of the biggest obstacles to salmon recovery is fish hatcheries. The massive declines of wild coho were masked by returns of fish to hatcheries, which now have also declined. But increasingly scientific studies are documenting the severe impact to wild fish of interbreeding with hatchery fish (Araki et al. 2007, Kostow 2009, Chilcote et al. 2011). Essentially, interbreeding reduces the reproductive capacity of wild populations by as much as 10 times, preventing recovery.

So what do we do? One way is to continue to follow the present path: arm-wave about the terrible state of coho salmon populations, take a few palliative measures (as the beleaguered, under-staffed State and Federal agencies are now trying to do) and then track the extirpation of coho from California. The coho salmon, like the grizzly bear, will become another quaint icon of California history.

In Part II, Moyle outlines the steps needed to prevent Coho extinction (note, this is not the same as “recovery”), which include:

- Improve hatchery management

- Protect remaining habitat

- Focus restoration efforts

- Improve coastal region land management practices

- Reclaim estuaries

- Remove dams (he points to Dwinnell Dam on the Shasta River)

CalTrout is fighting to restore California’s salmon populations — especially Coho populations on the Klamath, where the Scott and Shasta Rivers offer the hope of sustainable populations.

With salmon populations all over the state under siege from habitat loss, water quality issues and poor hatchery management, there’s no shortage of battles.

To see what we’re facing (at least on the Coho Salmon front), visit Part I and Part II of Moyle’s extensively annotated articles.

3 Comments

Here in Southern California we lost our last coho runs including in Malibu Creek more than 50 years ago.

When I lived in Fieldbrook in Humboldt County in the 1990’s our local Lindsey Creek supported a thriving coho population. Lindsey Creek’s watershed is and has always been entirely in private ownership.

Curtis Ihle (Fish Action Council) and I organized a 4-H project with the kids on Stream Stewardship. We planted trees donated by the logging industry along the stream banks, raised steelhead frye in a classroom incubator and released them into the North Fork Mad River, and did a visual survey for salmonids throughout the stream system that gave us some optimism about the creek’s aquatic ecosytem.

Most significantly, we got Larry Preston (CDFG fish biologist) to come out and do a small electroshock survey on a 100-foot reach of Lindsey Creek with the kids helping net the stunned fish. We found four salmonid species: coastal cutthroat trout, steelhead trout, a few 0+ chinook , and a bunch of 0+ coho juveniles that Larry said were the plumpest and healthiest he had ever seen. We also found one Pacific lamprey ammocete (larvae that live in the stream mud for 5 years then migrate to the ocean), a few speckled dace, and one California roach.

That’s seven species of native fish in one small coastal stream. We found not one non-native fish.

These fish survived because our community members that lived along the creek did everything we could to protect them. I am confident that even when coho die out from all the other streams in California, Fieldbrook coho will survive under the radar.