The CalTrout Interview: Anders Halverson, Author of An Entirely Synthetic Fish

National Outdoor Book Award Winner Speaks To CalTrout

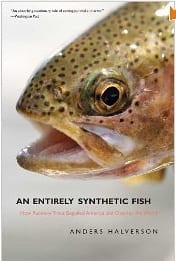

Anders Halverson is the author of An Entirely Synthetic Fish — a National Outdoor Book Award Winner and a riveting book about the spread of rainbow trout across the country, often at the expense of native species.

A biologist (he’s a Research Associate at the Center of the American West), Halverson has also worked as a journalist, which explains how he built a series of riveting narratives around fisheries management in the USA.

In addition to winning the National Outdoor Book Award, An Entirely Synthetic Fish has generated uniformly positive reviews. It uses the rainbow trout as a symbol for intrusive fisheries management techniques which have often decimated native species, and while you’d think a book on that subject would feel dry and technical, An Entirely Synthetic Fish is anything but.

On a recent book tour, Halverson spoke to several groups of CalTrout members, and graciously gave up some of his time for this interesting, wide-ranging interview for CalTrout’s The Streamkeeper’s Log.

The Interview

Q: Your book was something of a surprise; I expected a dry-to-the-taste-buds science book, and instead ended up reading a series of riveting stories.

That was my goal. When I decided to write the book,I was finishing a PhD in aquatic ecology. But I’d been a reporter before becoming a biologist, and I wanted to write a popular book about the history of freshwater fisheries management in this country. Somehow I convinced the National Science Foundation to give me a grant to do it.

I decided to write about rainbow trout to provide narrative focus. But ultimately, the book turned is really about people and how we’ve related to the natural world over the last 150 years.

Take the title. I’ve gotten a lot of feedback from people about that.

Q: It threw me too.

I want to state for the record that the title is meant to say more about us than the fish. It’s a quote from the director of the federal fish hatchery program who was moved to declare in 1939 that his agency was now capable of creating “an entirely synthetic fish.”

Q: Got it. Besides the title, what parts of the book do people react to most strongly?

The thing I hear the most about is the Green River “rehabilitation.” In 1962 we poisoned all the fish in a 15,000 square mile watershed so that it would be safe to introduce rainbow trout. It was such a massive project and nobody has really heard about it. But it was also a turning point in how we relate to native species and wilderness. In fact the backlash was one of the things that led to the creation of the Endangered Species Act.

Q: You mentioned that facts about the Green River project were hard to come by; how did you write the Green River chapter?

I expected to find all sorts of stories on the front pages of the newspapers from the day. But when I started going through the microfiche, I couldn’t find a thing. Finally, I found some stories in the sports pages. That’s almost the only place the project was covered–in stories that talked about how great the fishing was going to be.

It’s hard to believe in this day and age, but there was simply no controversy about the project at the time. Imagine the US Fish and Wildlife Service killing all the fish in an area the size of Connecticut and Massachusetts combined so they could introduce a nonnative species.

Q: They were poisoning a whole watershed and nobody cared?

Not really. About the only people who opposed it were the ichthyologists Robert Miller and Carl Hubbs, and they couldn’t get any traction. I finally got in touch with Jerry Smith (he was Miller’s grad student at the time), and he sent me many of those letters I referenced in the book. It was a real gold mine of information. I got lucky like that a couple times while writing the book.

Q: You began your book with the story of the McCloud River’s exploration; how did you research something that happened so long ago?

I had some information about Livingston Stone the fish culturist, but not a lot about Livingston Stone the human being. I traveled to many of his old haunts, but I was a little stuck.

Then I got a phone call from a woman who was Livingston Stone’s granddaughter, and it turns out she had all these letters and documents and she only lived a few miles away from me.

It was another stroke of luck that helped shape the book.

Q: I live not far from the McCloud River, and wonder where the original McCloud hatchery was located. Did you ever find it?

If you take the boat across the McCloud arm of the reservoir that runs to Shasta Caverns, you go right over it — it’s under about 300 feet of water now. From the highway, you can still some of the gray rocks that form the backdrop for a lot of the photos of the hatchery.

Q: Oh, it’s that far downriver. I’d guessed it was farther upstream, closer to McCloud Reservoir.

It was wilder back then — that was already a long ways from civilization.

Q: I hear a lot of people talking about the pure-strain McCloud Redband trout that were disseminated around the world, yet the hatchery was where Shasta Lake is today, so weren’t they collecting coastal rainbow eggs?

Probably. Back then they didn’t understand the relationship between steelhead, redbands and coastal rainbows. The trout were clearly McCloud River rainbows, but the distinct subspecies we know today as “Redbands” are really only located in the headwaters. They probably mixed them all up in their breeding program.

Q: You can’t help but have noticed the felt vs rubber wading boot wars; what’s your take?

Cleaning is clearly needed no matter what you’re wearing, but I’ve switched to rubber. It’s just easier to dry out and clean. I try to sterilize them.

You look at the impacts zebra mussels and Quagga mussels have had on some waters and you realize it’s no joke.

Q: The book contains a chapter about California’s Yellow Legged Frog, the battle over which is still happening.

I did my PhD on frogs. I wasn’t working on that particular issue, but I was certainly aware of it. Certainly people resist removing trout from some of those alpine lakes to protect frogs.

Q: It’s gotten pretty heated at times.

If I was speaking to someone who was upset about this, the first thing I would say is that it’s not just about frogs. There’s a whole fauna that evolved in and around those alpine lakes when there were no fish in them. Now that 95% of those lakes have fish, that whole ecosystem is being changed.

To me it’s a no-brainer; if by removing this fish from just some of the lakes we can help save entire species — from the frogs to the birds who eat the Callibaetis to everything else — then it’s an easy choice. They’re not going to eliminate trout form all the lakes, just a few of them.

It’s also important to remember that they stopped stocking in many cases because it appeared that not only was it not necessary to maintain the fisheries, it was causing stunting. In a lot of cases, not stocking just yields more, larger wilder fish.

Q: You mention you’re a fisherman too.

I am a fisherman; I grew up in Colorado, fishing with my dad. At some point, though, I just stopped. I didn’t really think about why until I started thinking about writing this book.

I think most people fish to get away from the industrialized world — at least I do. But there’s a paradox there. Most of the fish we catch are in many ways products of our technological society. That’s what caused me to stop fishing for a while, it’s what propelled me to write the book, and it’s also what caused me to pick up my rod again. I find fish more fascinating now than ever — they’re so layered with our own human culture and history.

Q: The question of hatchery fish weakening native stocks has really come to the forefront the last couple years, especially in regards to the northwest’s salmon and steelhead runs.

Yeah. There’s plenty of evidence to show that hatchery fish are far less fit. And they’re causing all sorts of problems with wild populations.

But I think it’s really part of a larger question; when you approach these problems, you can try to address the root, or you can look for a technological fix. If you go for the technological fix, you can be sure there will be unintended consequences.

And I think that extends to so many of the other environmental issues that we’re facing. When you play with complex systems, there is very little predictability. And so now, with many of the issues we’re wrestling with, we’re trying to fix some of the unintended consequences from previous fixes.

Q: Are hatcheries less harmful than they used to be?

Yes. They’ve gotten much smarter about the genetics and and other aspects of fish culture. For example, they’ve gotten much better about collecting and using wild fish in their spawning operations.

Nevertheless, whenever you raise something in a hatchery, it’s an artificial environment with very different selection pressures. The fish that come out are very different from the fish that are spawned in the wild.

My graduate work in frogs taught me that these systems are far more complex than we realize. We don’t have any real idea what’s happening out there.

For example, in one of my experiments, I put fences around these ponds and captured every frog that was coming into breed. I took a tissue sample from everyone. Then I used DNA fingerprinting to identify all their offspring, and it was clear that the frogs had somehow recognized their close kin and avoided breeding with them.

It was also clear that the more inbred the tadpoles were, the less likely they were to make it out of the pond.

Q: Wow.

The tools we have — we’re just wandering around out there with a bludgeon.

As another example, I recently heard a talk about a study in the Smokies (ED: Great Smoky Mountains National Park); they removed rainbows from a stream and stocked brookies from three different tributaries, and 15 years later, their offspring show no signs of interbreeding. Nobody knows why.

When we approach these problems, we need to recognize our limitations, and structure our solutions accordingly.

Q: Tell me about getting your book published.

All in all, it was a gratifying experience. Trying at times, but gratifying. It’s really a team effort — agents, editors, publicists and so on. And I worked with some great people who really improved the book. The copy editor comes to mind in particular.

Once I completed the book, it was a long time before it made it to the bookstore. That was hard, wondering how people would react. Because Yale is an academic press, they had to send it out for peer review. That took a few months. Two of the reviews were good, one not so much. But that was enough for them to go forward.

And the response since it was published has been tremendous. I never expected to receive so much attention.

Q: What about the writing process. Was that hard?

I don’t know how anyone does this; I don’t know how anyone writes books. I had this luxury — a grant from the National Science Foundation — without that, it would have been impossible to survive, much less provide for a family.

With that grant, I was able to do all this research and gather all this information without a lot of pressure from a publisher to get something to them at the end of the year.

That epiphany — the decision to focus on the rainbow trout’s spread instead of fisheries management as a whole — didn’t come until I’d been working on the project for at least 9 months.

Q: Publishing seems to be in a state of chaos, and I hear stories about publishers who seem unwilling to take chances or spend any money on a new writer.

I was told over and over again: don’t expect anything in terms of publicity.

That wasn’t my experience. The publicist at Yale Press was great. She got me an interview on the Diane Rehm Show on NPR, she got reviews in some good papers. I was really pleasantly surprised.

There was no book tour. That would have been fun. But I don’t know of anyone besides the biggest names who can get one of those these days.

Q: You’ve done the rest yourself?

I created my own website, and I’ve actually gone out and approached groups and given talks — if they’re willing to cover my travel expenses and a small stipend. I’ve reached out to radio stations, bloggers, and others like that.

Q: So how has the book worked out for you?

It’s been incredibly rewarding. It’s been great to get such good reviews. But the best part is that it’s allowed me to meet so many interesting and committed people.

Q: You met with a couple groups of CalTrout supporters?

I went around the state. I visited CalTrout groups in LA and San Francisco, and even stopped in the Mt. Shasta Region.

I learned a lot meeting with the CalTrout folks; Jeff Thompson is so full of knowledge and enthusiasm. Nica Knite (ED: CalTrout’s Southern California manager) makes a good argument that we ought to be doing more to protect southern California’s steelhead populations, especially in light of climate change. These fish might be best adapted to handling a changed climate.

Q: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk. We appreciate it.

You’re welcome. I had fun.

Visit Anders Halverson’s website

Follow Anders Halverson on Twitter

7 Comments

Great interview!

I like the new, useful (and informative) website a lot. Keep the bytes flowing!

Thanks for the feedback. We’ve got plenty more coming the next couple weeks — and make sure you’re signed up for our email list…