After almost a year, Sean Jansen, the writer and adventure junky retracing the 1,000 mile historic range of Southern California steelhead on foot is back. The next leg of his journey commences – from tideline to alpine.

By Sean Jansen

I got what I wished for. Since leaving San Clemente and getting started on this impactful trek in spring 2024 to raise awareness for the plight of Southern steelhead, I had done nothing but walk on exposed concrete and asphalt for 21 days and over 300 miles. Finally, I made it to the northernmost river in the range, the Santa Maria. Following that inland, I resupplied in the town’s namesake and prepared for the new chapter of the trip about to take place – the trek into the mountains where these steelhead and rivers begin.

The pack was heavy, the heat was incessant, and the climb was arduous, but I finally found myself on a dirt road in Los Padres National Forest, and the dread of what I was about to get myself into took over. If anyone has followed my journey throughout this trip, you might remember that I already took to the mountains last spring. However, I ultimately had to hitchhike around this near 200-mile section because I was chained by a timeline that forced me to skip ahead to the Pacific Crest Trail and hike to Big Bear. Though it was amazing to hike and see some of the wilderness areas along that infamous trail and see the drainages of the Santa Clara, the San Gabriel, and Santa Ana rivers, skipping this wild section of the trip bothered me.

It bothered me so much that I had no choice but to return. I wanted to return with ample time to explore the intricacies and magic of the landscape to giveit the justice it deserves, and more importantly, let it speak the words it must and honor the demands it presents. From Santa Maria to roughly Acton, the landscape is wild, remote, and untouched – arguably the most untouched wilderness area in all of Southern California and the historical range of these fish. An impenetrable wilderness of over half a million acres and a mix of high desert chaparral as well as alpine pines.

I left Santa Maria last spring and began my trek into this wilderness on a dirt road that was so overgrown with grasses and bushes that they tickled the waist band of my backpack while I walked. Trails were nonexistent and what remained of them were dilapidated trailhead signs that too, had been engulfed in overgrown reeds and greenery. It all reminded me of a scene from Jurassic Park where the jungle had taken over the compound. And although the terrain forced me to abandon the section because of my time frame, I was excited to return and come back – with a machete if necessary – and hack through the wilderness in search of this untouched beauty. In search of this solitude, and of course, in search of its fish.

I was dropped off exactly where I exited the wilderness last spring and began my trek along the spine of the range with sweeping views down to one of its steelhead rivers, the Sisquoc (meaning quail in the native Chumash language). As I laid my eyes on the slithering river, one of our state birds shot out from a bush and startled me. Perhaps I was so focused on the gorgeousness of the river that I hadn’t thought about any potential wildlife, but the moment the quail darted out and flew right by, I had a feeling I would be not be traversing this range alone. That feeling that turned out to be true.

Most of the areas I hiked through in this National Forest looked entirely unexplored. The trails - as expected - also reflected that. Overgrowth was an understatement and much of the trek across this wilderness area was that of route finding, stepping through thigh deep grasses, bushwhacking through spine riddled and tick covered small trees and greenery, and walking along creek banks or simply walking rivers.

The terrain wasn’t the only thing to hamper the progress. Each blade of grass, bush, or tree had either spiders, ticks, or a snake hiding underneath. The weather turned rapidly from spitting snow on the peaks and ridgetops to incessant heat, leaving me itching to dip in the water. Anytime I’m itchy, my mind is immediately consumed by thoughts of poison oak, sumac, or perhaps other poisonous, or venomous things I had been bitten by or brushed up against in the past. This fear is balanced by the one constant in this area – an experience of complete solitude.

I often found myself high above drainages with nothing but the sound of the wind, the call of red-railed hawk, or the tumble of water. This felt like the perfect time to take a break by leaning against a rock, a sand bank, or even a pine tree. I went eight days without seeing a human and thought that would really put a strain on my focus, my mental health, my sanity. But ultimately, it fed my soul and desire to keep going.

But I was constantly reminded that I was never fully alone. The red-tailed hawk would fly above and look over me, and even a condor presented itself with a sideways glance of the head with the white under-side of its wings confidentially ensuring me of its identity. The paw prints of a black bear often guided me through one creek drainage after the next, notifying me that it was the path of least resistance, even the rattlesnakes that rattled at my presence almost seemed to cheer me on while I daintily stepped out of their strike range. But the real drive, the real fuel for this engine - powering me through this rough, rugged, and untouched wilderness, were the fish.

Each creek, each river, and each drainage, no matter how rough, how cold, how hard to get to - had a healthy population of salmonids. Trout would either sit in the deep and slow-moving pools while gently swaying with the subtle current or they would dart in and out of cover in the boulders of the creeks. Some were out in the open, clearly visible in the springtime light, while others required an in-depth GoPro search. . I witnessed a variability in size as well. Some were no larger than my index finger while others were well over 20 inches in length, with one being close to two feet. It’s hard to say if any were recently anadromous, or able to access the ocean, but they all, at least historically and genetically had the capacity to go from freshwater to ocean, a miraculous life history trait preserved in even those fish locked behind barriers.

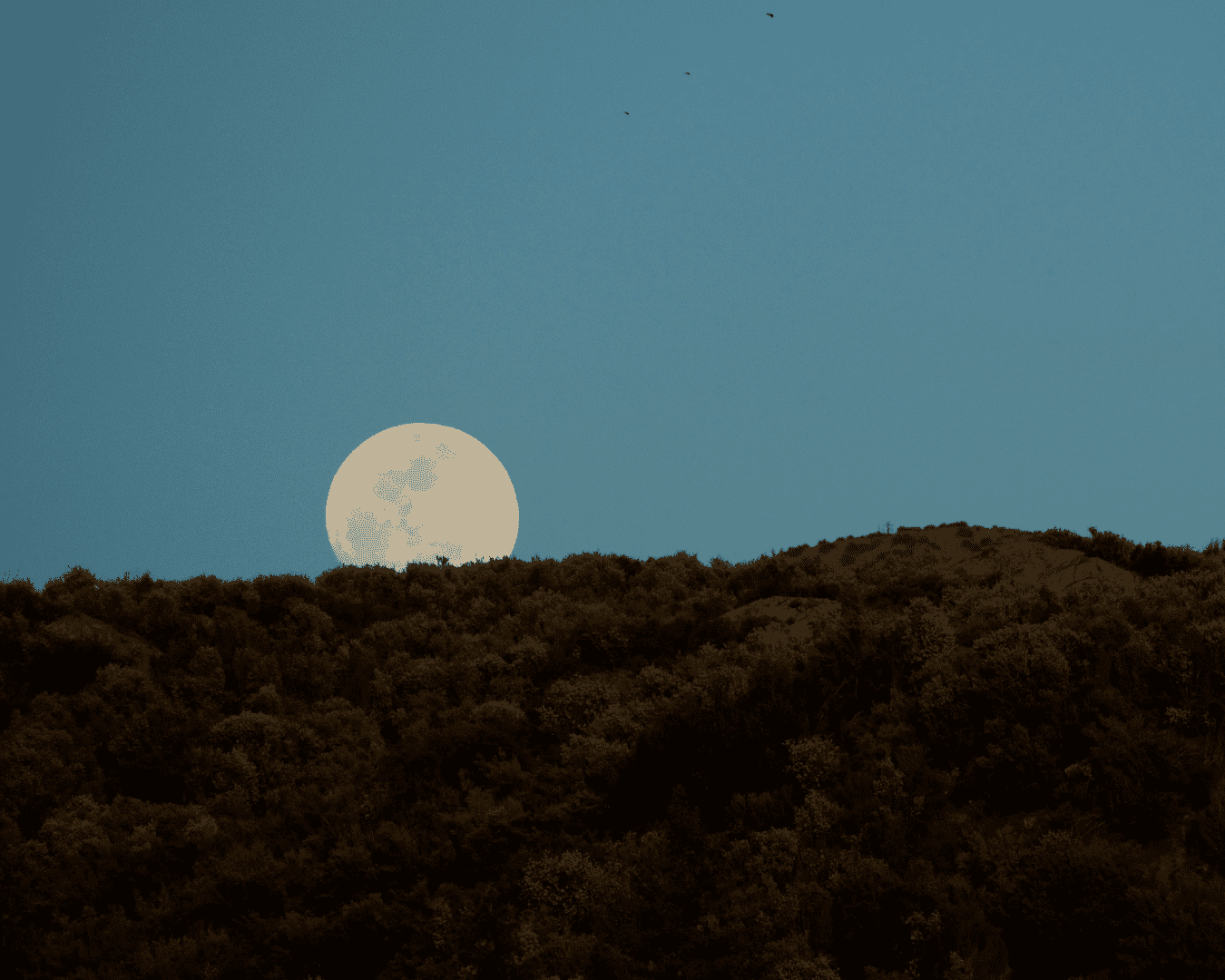

I often watched them in awe while I took a creek-side break, eating my dinner next to camp, or sometimes even over morning coffee - watching them come up and out from structure while the sun rose in the sky. The sun was my daily alarm clock for each day, and not just for me but for a litany of creatures, including the fish. The full moon was the light switch at night that reminded me of bedtime while keeping me comfortable in the depths of the wilderness.

In 14 days, I made it 172 miles across three wilderness areas and successfully traversed the southern district of the Los Padres National Forest. I made my way into the town of Santa Clarita and walked along the streets noticing the most horrifying reminder of my youth - Six Flags Theme Park. I used to sit on the benches paralyzed with fear while my friends’ rode the roller coasters. I was and always will be far more comfortable in the wilderness than anywhere entirely man-made. But I followed the dried-up riverbed of the Santa Clara to Acton where I met up with the Pacific Crest Trail, connecting the line that I had skipped over last spring.

The remaining part of the trip from Big Bear to the U.S. Mexican Border to the Tijuana River will only be possible depending on forest closures from the fires of 2024. I really hopethat this coming summer and fall will be one of safe fire suppression and responsible outdoor recreation. All I need is a safe window to successfully circumnavigate this range and finish this trip. Whether I will be able access to these last few remaining areas depends on the climate. And it’s not just about my safe passage - conditions that would allow me to pass through this area would also provide safe refuge for fish to pass through.

Stay tuned for Sean’s attempts to traverse the final segment of historic Southern steelhead habitat range!