How we're working to save them:

- Use legal tools such as Assembly Bill 2121 minimum flow requirements, Fish and Game Code 5937, and the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act to secure water in streams, especially during critical summer and fall months.

- Restore estuary habitat and function for juvenile steelhead and other salmonids.

- Implement CDFW’s statewide coastal salmonid monitoring program to collect abundance, life history, and population data to inform recovery efforts.

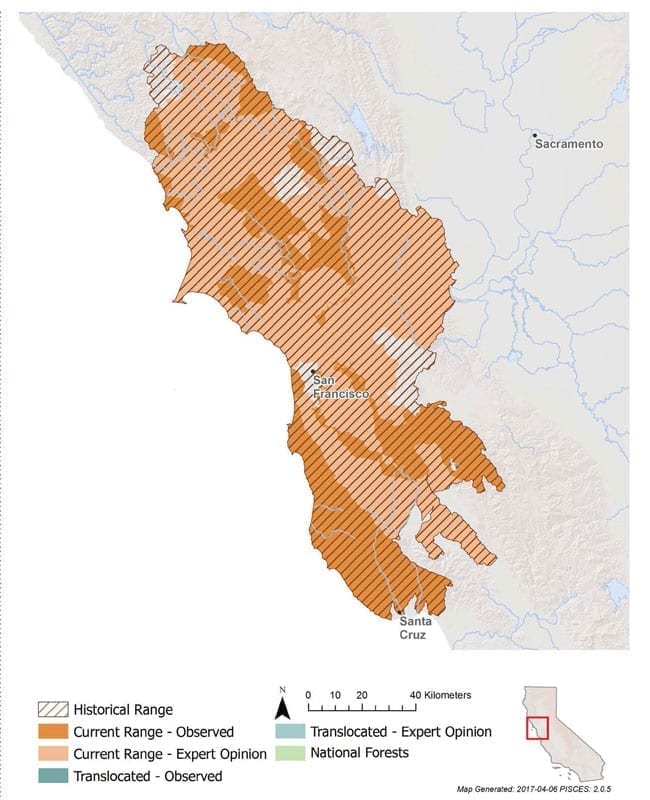

Where to find Central California Coast Steelhead:

Central California Coast steelhead Distribution

Central California Coast steelhead range from the Russian River (Sonoma County) south to Aptos Creek (Santa Cruz County). Within the San Francisco Bay Estuary, CCC steelhead are found in the Guadalupe and Napa rivers, and San Leandro, San Lorenzo, Coyote, San Francisquito, San Mateo, and Alameda creeks. Populations of CCC steelhead still reside in the upper reaches of streams that feed reservoirs, such as Upper San Leandro Reservoir upstream of Chabot Dam. Some small coastal streams south of the Golden Gate Bridge also contain CCC steelhead, such as Pilarcitos and Pescadero creeks in San Mateo County and Scott and Waddell creeks in Santa Cruz County.

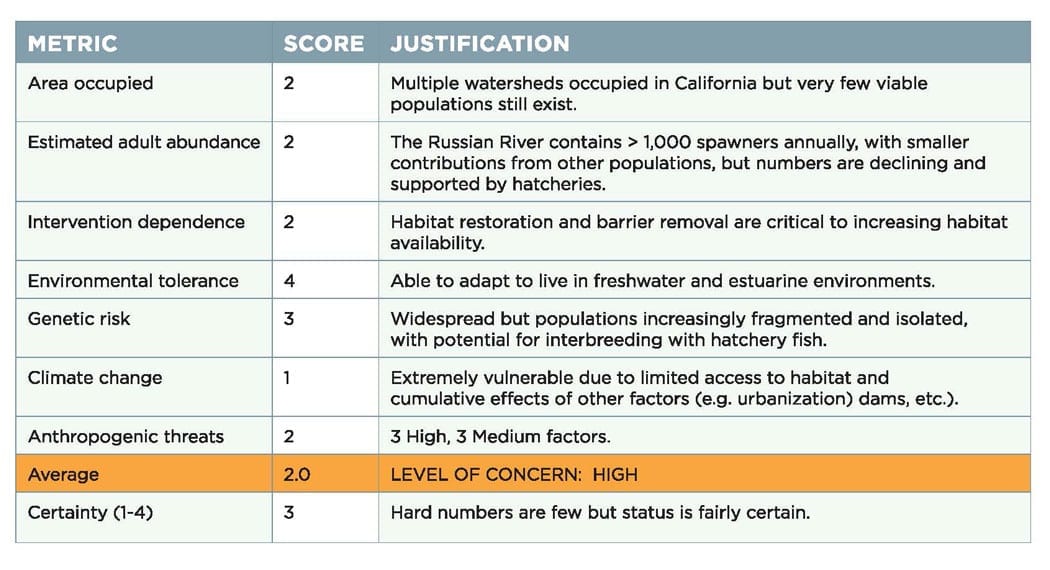

How the Central California Coast steelhead Scored:

Characteristics

Central California Coast steelhead are anadromous coastal Rainbow trout that live downstream of manmade barriers throughout their range. They are very similar to Northern California winter steelhead in appearance.

Abundance

Historical abundance estimates of Central California Coast steelhead are limited. During the early 1960s, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife estimated about 94,000 CCC steelhead spawned throughout their range, with most spawning occurring in the Russian (50,000) and San Lorenzo rivers (19,000). With the exception of hatchery-raised steelhead from the Warm Springs Hatchery on the Russian River, most watersheds support less than a few hundred adult steelhead per year. Current populations are likely less than 10% of these historical estimates. For example, CDFW has not documented spawning steelhead in San Francisco Bay tributaries since the drought started in 2012.

Habitat & Behavior

All CCC steelhead are winter-run fish, entering freshwater as mature adults during the highest flows of the year, typically between late December and February. Adults returning to freshwater are mostly three and four years old, and typically spawn during late spring (February to April). With favorable flow and temperature conditions, female steelhead may spawn and return to saltwater in only a few weeks, while male fish may linger and spawn multiple times before returning to the ocean. Eggs hatch after about a month in the gravel, with fry emerging and beginning to feed about three weeks later. When juvenile steelhead reach about 10 cm (about 4 in.) in length, they begin to smolt and migrate downstream during spring and summer months to seek out foraging opportunities in larger mainstem rivers or critical estuaries and lagoons. Smolts spend up to two years or more in larger rivers and estuaries putting on weight and roughly doubling in length before their arduous journey to the Pacific Ocean. Once at sea, CCC steelhead migrate to cool waters offshore of the Klamath-Trinidad coastline before moving to feeding grounds in the North Pacific with steelhead from other regions.

Genetics

CCC steelhead are more closely related to more southerly steelhead populations south of Monterey Bay than they are to populations north of the Russian River. Steelhead from the Russian River (Sonoma County) south to the Golden Gate Bridge form a distinct genetic group, while steelhead from the Golden Gate Bridge south to Big Sur form another.

- All

- _proof

- 50th

- Action Alert

- Bay Area

- Bay Area

- Blue Ribbon Waters

- California Water

- CalTrout People

- CalTrout Promo

- Campaigns

- Central Valley

- Central Valley

- Dams

- Diversity Equity Inclusion

- Eel River

- Event

- Events

- Featured

- Featured Watersheds

- Field Notes

- Fly Fishing

- From CalTrout

- Fun

- Hat Creek Restoration Project

- Imperiled Native Trout

- Initiatives

- Integrate Wild Fish & Working Landscapes

- Integrate Wild Fish & Working Landscapes

- Integrate Wild Fish and Working Landscapes

- Invasive Species

- Job Postings

- Key Initiative

- Klamath River Restoration

- Legal & Policy

- Legislation

- Migration Matters

- Mount Shasta / Klamath

- Mt. Lassen

- Mt. Lassen

- Mt. Shasta/Klamath

- News

- North Coast

- North Coast

- Podcast

- Podcast

- Press Releases

- Protect The Best

- Protect the Best

- Protect The Best

- Protect The Best

- Reconnect Habitat

- Reconnect Habitat

- Reconnect Habitat

- Regions

- Restore Estuaries

- Restore Estuaries

- Restore Estuaries

- Science

- Science Into Action

- SCRSC

- Sierra Headwaters

- Sierra Headwaters

- SOS Report

- South Coast

- South Coast

- Steelhead & Salmon

- Steward Source Water Areas

- Steward Source Water Areas

- Streamkeeper's Blog

- Trout

- Uncategorized

- video

- Voices of the Watershed

- Water Talks

- Women of CalTrout

- Youth

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.