Sunol Valley Fish Passage Project on Alameda Creek

Sunol Valley Fish Passage Project on Alameda Creek

Project Stages

Planning

Conceptual Design

100% Planning, Design, and Permitting

Implementation

Post-Restoration Monitoring

Outreach

Estimated Completion Date:

2026

Region:

Project Funders

PG&E

NOAA Fish Passage Grant

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

Fish Affected:

Threats:

Project Description

Alameda Creek is the largest local tributary to the San Francisco Bay and historically produced the largest numbers of Chinook salmon, lamprey, and steelhead in the South Bay. It is also the ancestral lands of the Muwekma Ohlone people. In 2022, former barriers at the BART weir and inflatable bladder dams in Fremont were made passable by fish due to newly constructed fish ladders by the Alameda County Water District. This incredible opportunity for salmonids to migrate throughout the Alameda Creek watershed is the product of decades of hard work to improve fish passage by a myriad of partners in the longstanding Alameda Creek Fisheries Work Group, including the Alameda County Water District (ACWD) and Alameda County Flood Control & Water Conservation District, Alameda Creek Alliance (ACA), California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), Zone 7 Water District, Alameda County Resource Conservation District, Trout Unlimited and the National Marine Fisheries Service, among others.

CalTrout staff have engaged in the Fisheries Work Group since 2019 and were thrilled to add our skills to address the hard work of barrier removal and restoring ecological function further up in the watershed. We have assisted local partners and trained volunteers to conduct spawning surveys along Alameda Creek since 2022.

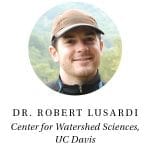

The last remaining barrier on mainstem Alameda Creek was in Sunol Valley near the intersection of Interstate 680 and State Route 84. It was created by a protruding layer of concrete across Alameda Creek that protects a major gas pipeline owned by Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E). The concrete prevented passage for migratory fish during most stream flows. As California’s cycle of drought and deluge continues, resolving this barrier to fish passage ensures fish access upstream regardless of their species, life stage or size, and if it’s a wet or dry year. Project implementation began in summer 2025 and as of fall 2025, fish have access into the highest quality habitat remaining in the watershed in and upstream of Sunol Regional Park.

The gas pipeline was moved about 100 feet downstream and lowered approximately 18 feet beneath the creek bed, so there is no longer a need for the protective concrete layer. The former pipeline and associated concrete were removed after the new pipeline was tied in. PG&E developed the pipeline burial designs and executed all pipe work. Following the pipeline burial, the creek was regraded to create a dynamic channel and disturbed areas werre revegetated with native plants. The restoration design plans were developed by Applied River Sciences, a crucial project partner that CalTrout has worked with for many years in our North Coast and Mount Shasta regions.

As the project lead, CalTrout coordinated all project partners for permitting and grant funding applications. CalTrout also led the implementation effort and will continue to lead post project monitoring. Important project partners are PG&E, San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (landowner), DeSilva Gates Aggregates, Martin Marrietta Materials (both lease land on each side of Alameda Creek from SFPUC for quarry operations), Hanford ARC (restoration construction), Sequoia Ecological Consulting (biological compliance), Stantec Consulting Services (cultural compliance), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (funder and NEPA lead), San Francisco Planning (CEQA lead), Alameda Creek Alliance, and more.

Alameda Creek flows by and through hundreds of Bay Area residents’ backyards. This project helps build an even greater appreciation for the salmon and steelhead that have traveled all the way from the ocean.

Project Partners:

McBain Associates

PG&E

San Francisco Public Utilities Commission

DeSilva Gates Aggregates

Hanford ARC

Alameda Creek Alliance

NOAA

Sequoia Ecological Consulting

Stanec Consulting Services

Martin Marietta Materials

Human use of streams, lakes, and surrounding watersheds for recreation has greatly increased with population expansion. Boating, swimming, angling, off-road vehicles, ski resorts, golf courses and other activities or land uses can negatively impact salmonid populations and their habitats. The impacts are generally minor; however, concentration of multiple activities in one region or time of year may have cumulative impacts.

Human use of streams, lakes, and surrounding watersheds for recreation has greatly increased with population expansion. Boating, swimming, angling, off-road vehicles, ski resorts, golf courses and other activities or land uses can negatively impact salmonid populations and their habitats. The impacts are generally minor; however, concentration of multiple activities in one region or time of year may have cumulative impacts.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.