The Klamath River flows 253 miles from Southern Oregon through the mountains of far Northern California where it passes five hydropower dams before ultimately reaching the California coast, draining a basin of more than 10 million acres. The watershed is renowned for its majestic lakes, rivers, fishing opportunities, and strong agricultural economy.

The Klamath River Watershed is home to six federally-recognized Tribes (the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, Shasta, and Klamath tribes, plus Quartz Valley Indian Reservation and the Resighini Rancheria) who lived off and tended to the fertile lands for thousands of years before European colonization. Today, Tribal nations control approximately 10 percent of the watershed while 60 percent is managed by public agencies (such as the National Park Service) and 30 percent is privately owned.

Location:

Northwestern California and south-central Oregon

Size:

Over 10 million acres; drains the third largest river south of Canada flowing into the Pacific Ocean

Communities served:

5 California counties and 3 Oregon counties; most populous towns are Klamath Falls, OR (19,462) and Yreka, CA (7,290)

Key native fish in the watershed:

Chinook salmon, coho salmon, steelhead

BREAKING NEWS ON KLAMATH DAM REMOVAL

On Nov. 17, 2022, an important step was made towards implementing what will soon be the largest U.S. river restoration project to date with the removal of the lower four Klamath River dams. A License Surrender Order for the Lower Klamath River Hydroelectric Project has been issued by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The project license will now be transferred to the States of Oregon and California and the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the non-profit entity tasked with overseeing dam removal and related restoration efforts. Dam removal is set to begin in early 2023 and by end of 2024, all four Klamath dams will be gone.

Read more about this historic decision.

Voices of Klamath River Watershed

Hear from individuals that work, play, and/or live in the watershed.

Featuring videos from Reconnect Klamath, a coalition of groups,

including CalTrout, working to support dam removal and Klamath River restoration.

Dr. Ann Willis

California Regional Director,

American Rivers

“These rivers are so complex. The different pieces of them come together in such a mysterious and miraculous way. It's foolish to try and predict the outcome of [dam removal], and I think it's almost more magical to be surprised by it and to choose to be open to learning what we don't know.”

Barry McCovey

Yurok Tribe Member

Yurok Tribe Senior Fisheries Biologist

“The Yurok Tribe are ‘fix the world’ people. Our high ceremonies dictate that we restore balance to the world. For those of us participating in these ceremonies (not all Tribal members do), that’s who we are and why we believe we were put on this earth. Looking at the Klamath River today, it is bisected by four dams, cutting off the energy flow. That is the definition of imbalance in an ecosystem. Pulling those dams out of the river and reconnecting the lower and upper basin for the first time in 100 years will be very meaningful to the Yurok people and other Tribes.”

JP Thompson & James Rickert

Farm Managers, Belcampo

“It’s important to us that we are good stewards of the land, and it’s also important to us that we exemplify how we might have productive relationships with groups like CalTrout.” - JP Thompson

“Our occupation is ranching, and we still need to have a job on these ranches. But we want to be very respectful of the watershed, and we want to do what we can to be as sustainable a ranching operation as possible." - James Rickert

Mark Bransom

CEO, Klamath River Renewal Corporation

“I never miss an opportunity to say that the Renewal Corporation is standing on the shoulders of the Tribes, the conservation community, and all others who have been fighting the good fight for so long.”

Robert Lusardi, Ph.D.

CalTrout-UC Davis Wild and Coldwater Fish Scientist

“I think of rivers as like the arteries in your body. Arteries deliver blood and oxygen throughout the human body, similar to how rivers deliver organic matter throughout the watershed. When that river is severed by a dam, the river can no longer function as it did for thousands of years. This has major implications for the ecosystem.”

Pergish Carlson

Yurok Tribe Member

Owner, Blue Creek Guide Service

"This is my home, where I’ve called home. The Klamath River is where my family is from… I’ve seen the Klamath water in winter and spring when it’s cold, clean, and crystal clear, then later in the year, as the water warms and slows, you start seeing the algae which affects the fish big time. But with restoration, it’s been shown that if you help the river a little, then leave it alone, it will come back. Everything heals in time.”

John Rickard

Wild Waters Fly Fishing, Owner

“Driving up and down the Klamath River’s corridor, you’ll see a lot of defunct fishing lodges, which shows us that at one time, the river was able to support a lot of fishing. I’ve been following the Klamath Dam removal project for a while. Our business of taking people fishing will be affected by it in the short run, but I am perfectly willing to give up a couple years of guiding this river if that’s what it takes to get it to recover. I’m excited to see the Klamath River go through a great change for the better.”

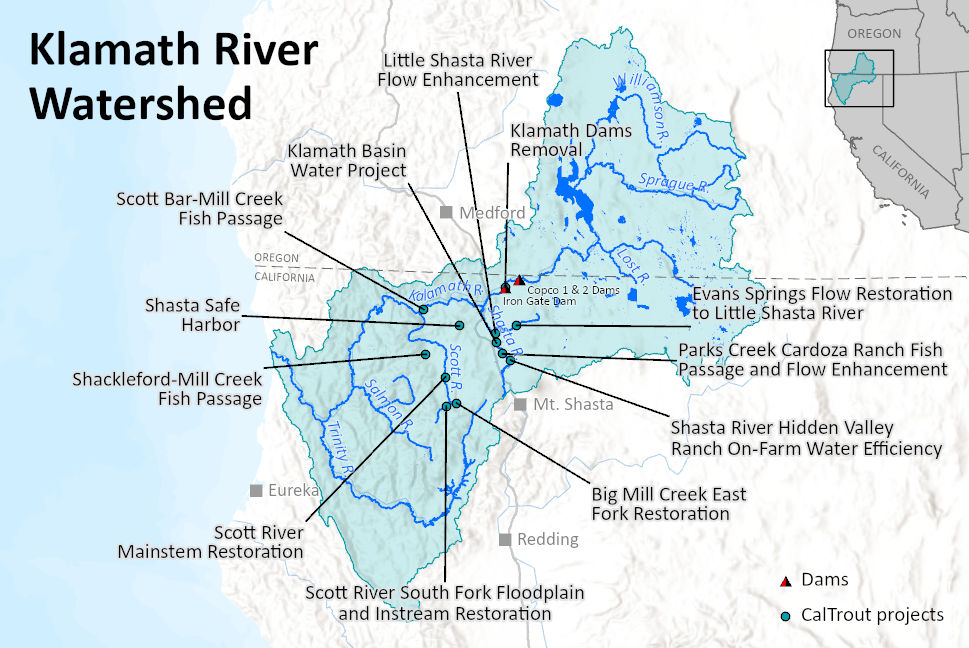

CalTrout in the Klamath River Watershed

CalTrout is working to protect and revitalize the Klamath River Watershed by addressing major threats to its health including fish passage barriers from the Klamath dams, loss of critical habitat, and water mismanagement. While dam removal is a critical part of reviving the health of the watershed, so is restoration of important Klamath River fish spawning and rearing tributaries like the Shasta and Scott rivers. This will allow fish to more easily access and recolonize the upper Klamath River above the dams.

Read more about our Klamath River Watershed projects in the links below.

Get Involved!

Subscribe to CalTrout’s newsletter & action alerts to stay informed on the Klamath Dams Removal project.

Support CalTrout's ongoing and future restoration projects in the Klamath River watershed.

Show your support for the removal of the Klamath dams. "UnDam the Klamath" t-shirts and mugs are available in the CalTrout gear store. Don't miss out on these limited editions items created by local artist Ben Engle.

Find these items in our Apparel and Drinkware sections in the gear shop.

Cover photo by Val Atkinson.

- All

- _proof

- 50th

- Action Alert

- Bay Area

- Bay Area

- Blue Ribbon Waters

- California Water

- CalTrout People

- CalTrout Promo

- Campaigns

- Central Valley

- Central Valley

- Dams

- Diversity Equity Inclusion

- Eel River

- Event

- Events

- Featured

- Featured Watersheds

- Field Notes

- Fly Fishing

- From CalTrout

- Fun

- Hat Creek Restoration Project

- Imperiled Native Trout

- Initiatives

- Integrate Wild Fish & Working Landscapes

- Integrate Wild Fish & Working Landscapes

- Integrate Wild Fish and Working Landscapes

- Invasive Species

- Job Postings

- Key Initiative

- Klamath River Restoration

- Legal & Policy

- Legislation

- Migration Matters

- Mount Shasta / Klamath

- Mt. Lassen

- Mt. Lassen

- Mt. Shasta/Klamath

- News

- North Coast

- North Coast

- Podcast

- Podcast

- Press Releases

- Protect The Best

- Protect the Best

- Protect The Best

- Protect The Best

- Reconnect Habitat

- Reconnect Habitat

- Reconnect Habitat

- Regions

- Restore Estuaries

- Restore Estuaries

- Restore Estuaries

- Science

- Science Into Action

- SCRSC

- Sierra Headwaters

- Sierra Headwaters

- SOS Report

- South Coast

- South Coast

- Steelhead & Salmon

- Steward Source Water Areas

- Steward Source Water Areas

- Streamkeeper's Blog

- Trout

- Uncategorized

- video

- Voices of the Watershed

- Water Talks

- Women of CalTrout

- Youth

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.

Dams block access to historical spawning and rearing habitats. Downstream, dams alter the timing, frequency, duration, magnitude, and rate of change of flows decreasing habitat quality and survival.